We can view the Classic Maya, not as a “less developed” society trying only to control the forces of nature and to survive economically. Instead, they can be regarded as fellow travelers—who simply chose a different path— through the darkness.

—Arthur Demerest

Mesoamerica and the Classic Maya Mesoamerica—Chiapas, Tabasco, Yucatán Peninsula in Southern Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Belize— was the home of a number of civilizations. Mesoamerica is a region of tremendous environmental diversity. The uplands include volcanic mountains and various types of tropical forests and the lowlands are tropical. One of the civilizations of Mesoamerica was the Classic Maya (AD 300–900) of the “Maya lowlands” the humid subtropical rainforests of Guatemala, Belize, western Honduras, and the Yucatan peninsula. Features of the Classic Maya appeared centuries earlier at sites in both the lowlands and highlands. Like the Pueblos of the Southwest, the Maya still live in the area and speak their native languages, although they no longer live in kingdoms with elaborate architecture.

Like the later Southwest Cultures and the Mississippian, the Classic Maya were reliant on maize along with beans and squash for food. They supplemented this diet with fruit trees and cacao (bean from which chocolate is made), kept bees for honey, and hunted animals of the rainforest. In the Maya lowlands, there are a variety of microenvironments, but generally, soils are thin and delicate, and easily exhausted. The Classic Maya used a diversity of techniques to farm these diverse environments. In addition to the three staple crops, the Maya had stands of fruit trees, like avocado and papaya, and left areas of rainforest uncleared for hunting and fuel. They used a number of different farming strategies including slash and burn (also called swidden), where areas were cleared, burned, and then farmed. This technique eventually depletes the soil, and the area must be left to rejuvenate and a few years. This practice continues among the Maya today.

The Classic Maya likely left more massive trees standing which would have allowed the rainforest to recover more easily. Also, the use of human waste as fertilizer would have improved production. Another technique used was terrace farming in which hillslopes were leveled into “steps” and the constructions of retaining walls which reduced erosion and kept in moisture. A third technique was used in swampy areas; sediments in these areas were piled up and cultivated. These “raised fields” are called chinampas. Box gardens, where soil and muck were brought in from swampy areas have also been documented.

Most of the populace of Maya centers lived in dispersed communities in and around major centers. The center of Classic Maya fluorescence, the Peten of Guatemala, was far more populated in the past than it is today. Today, modern farming techniques focus on single crops and widespread clearing and have destroyed vast stretches of rainforest in this area. One of the most studied periods of the Maya is the Classic Maya (AD 300–900). The Classic Maya had several distinguishing traits:

- Competitive “kingdoms” or interacting polities

- Divine kingship (called K’uhul Ajaw)

- Ceremonial centers with masonry pyramids

- Elite burials

- Warfare

- Ball courts

- Mural paintings

- Decorated ceramics

- Writing

- Calendars (general obsession with time)

- Maize agriculture (slash and burn, chinampas, terraces)

The Classic Maya society was hierarchical with a number of different classes of people. The ruling

class included kings who also served as priests, along with their families. That is, there was no separation of church and state. Rulers were associated with divine beings, not unlike Julius Caesar being descended from Aphrodite. This state of affairs is in no way uncommon in the history of civilizations. The ancient Egyptian pharaohs claimed to be gods, the Babylonian ruler Hammurabi claimed to be appointed by God, and the Mycenaean kings had absolute power. Yale historian Donald Kagan suggests that it is we who are the “oddballs” in separating the affairs of church and state. Those that threaten this system, he adds, have the weight of human experience on their side.

Elite Maya women participated in bloodletting rituals and other ceremonies, but rarely held political power. In the absence of a male heir, women could serve as regents or occasionally queens, and pass on the title. The nobility were titled people, scholars, architects, merchants, warriors (women sometimes held noble titles). Commoners were farmers and laborers, which included the majority of the population. Finally, Maya society also consisted of slaves, criminals, and prisoners of war.

The Classic Maya were organized into competing kingdoms. Warfare was commonplace and victories and defeats were recorded on Maya stone monuments. They competed through ritual pageantry and conspicuous consumption— ostentatious building projects and elaborate prestige goods like carved jades and liquid chocolate. Early scholars of the Maya, before the Maya writing was deciphered, thought that the Classic Maya were peaceful gentlemen scholars, debating finer points of science and art in their jungle campuses. This romantic view turned out to be only partially true; The Classic Maya were no different from any other complex culture—with warfare, science, writing, and great art. Divine Rulers Maya kings were especially important to the Classic Maya. They were the embodiment of the axis mundi or World Tree, the divine connection between supernatural worlds and this one. Rituals and pageantry associated with the K’uhul Ajaw served to propitiate the gods.

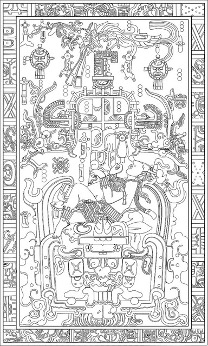

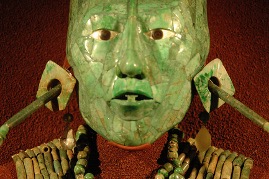

These divine rulers were buried within the masonry temples themselves. At the Maya site of Palenque, ruler Lord Pacal (K’inich Janaab’ Pakal) was buried deep within the Temple of Inscriptions. The stairway leading to his sarcophagus was filled with rubble that took four years to remove. The five-ton sarcophagus depicts the deceased Pacal lying at the base of the World Tree (axis mundi) falling into the Great-Maw-of-the-Underworld, based on standard and well-known Mesoamerican iconographic representations. Maya kings were the personification of the World Tree connecting the planes of the Maya cosmology. The sarcophagus was famously interpreted by popular writer and convicted con-man Erich Von Daniken as Pacal piloting some form of flying craft—apparent evidence of the extra-terrestrial nature of the Maya culture.

Inside the sarcophagus was a jade mask of the deceased ruler. Jade was a highly prized exotic raw material used in the production of esoteric ritual paraphernalia. These items were used in public displays to verify the social status and supernatural sanction. Beads, ear spools, and shells filled with red ocher were found (remember the 100,000-year-old Blombos in South Africa?). For most of the Maya populace, the deceased were buried beneath the floor or in shrines, typically including only a pot or two. The discrepancy in the burial of different members of the population is called burial hierarchy and is a common piece of evidence archaeologists used to identify differences in wealth and power.

As we have seen, humans, in general, are interested in their appearance, decorating themselves since the Upper Paleolithic, and gazing in pyrite (Hohokam) and obsidian mirrors (Catalhoyuk). The Classic Maya were no different. The elite, in fact, strove to look dramatically different from everyone else and engaged in some remarkable body modification. Most striking are the long, sloping foreheads of the elite created by binding that reshaped the skull. Ears, noses, and lips were pierced. Jewelry was made from jade, shells, wood, and bodies were tattooed and painted. Commoners also decorated themselves, enhancing their teeth with inlaid stones.

Classic Maya “kingdoms” centered around masonry four-sided pyramidical temples, elite residences, plazas, and ballcourts. In the early 1900s, the Maya were believed to reside in vacant ceremonial centers, inhabited by small groups of priests (Remember that this is also an idea regarding the use and function of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico). It was thought that the thin delicate soils of the rainforest could not sustain large populations. The priests were thought to direct rural, peasant populations through periodic rituals at the centers. More recent investigations have revealed thousands of mounds at the site of Tikal in Guatemala that has been identified as residential structures, indicating that thousands of people lived in these centers. Maya commoners lived in wattle and daub, stick and mud houses, houses on low mounds around the ceremonial center, similar to these houses used by the Maya today. The dispersed nature of Maya farms and the variety of farming techniques allowed the Classic Maya to flourish in a delicate area. At Tikal and other Classic Maya centers, most people lived in more modest homes of wattle and daub. In the lowlands, these houses were built on low earthen mounds to keep them above the water. While these more ephemeral (short-lived) houses are now gone, the mounds they once stood one remain. Archaeologists use mounds to identify where farmers lived and how populated the area around major centers was. Among the Classic Maya, people were loosely distributed in farming villages out from the center.

Maya House Mound. “Ruins Unsettled” by Josh Kellogg is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Modern-day Maya house, “La vida de los mayas en México, desde la península de Yucatán-5” by Ana Ruth Rivera is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0

The site of Tikal located in the Peten Basin of Guatemala is not only a World Heritage Site, but is also featured as the rebel base in Star Wars! The site has two temples facing each other —Temples I and II—on either side of a great plaza or court. Temple I was built as a mausoleum for ruler Jasaw-Chan-K’awiil. The carved wooden lintel on Temple II depicts a royal woman, perhaps Jasaw- Chan-K’awiil’s principal wife, who was buried there. The exceptionally hardwood of the Zapote Tree was used for lintels to hold up the temple doorways. The Temple of the Great Jaguar (Temple I) is over 150 feet high. The tops of the pyramids were rooms used for sacred ceremonies. The whole thing was topped with a roof comb. Tikal’s lords lived and conducted their activities in the Central Acropolis, south of the great plaza, spreading over four acres and containing 42 multistory buildings. The acropolis at Classic Maya sites grew from repeated rebuilding and expansion resulting in “hills” of architecture. The north side of the plaza is framed by the North Acropolis, a huge platform that appears to have been a burial place for Tikal’s nobles. Several other examples of monumental architecture are found at Tikal and these are connected by causeways or scabies. These were raised paths covered in white plaster that linked buildings to the Great Plaza. These roadways connecting important monuments might remind you of the Great Hopewell road connecting moundbuilders sites or even the road system at Chaco Canton.

Maya Religion

Maya religion reflected the fundamental role of agriculture in their society. The Maya creation narrative, the Popol Vuh, recounts Maya creation in which the gods created human beings out of maize and water. The Hero Twins figure prominently in the Popol Vuh (and also appear in Pueblo narratives in the Southwest and perhaps on Mimbres pottery). In the Maya religion, gods kept the world in order and maintained the agricultural cycle in exchange for honors and sacrifices. The Maya believed the shedding of human blood would prompt the gods to send rain to water the maize. Sacrifice took many forms, including auto-sacrifice, the offering of one’s own blood, especially the K’uhul Ajaw. Elite women performed bloodletting rituals in which they collected blood from their tongues onto paper and sacrificed it by burning it; men practiced genital bloodletting. One lintel depicts a bloodletting rite with a vision serpent. Lady 6-Tun, a wife of Bird Jaguar, has used the stingray spine in her basket perhaps to make a hole in her tongue. The rope is then run through the hole to collect the blood, which drips onto the bark paper. Bloodletting also involved prisoners of war. The frescoed murals at Bonampak in Chiapas, Mexico in the Temple of the Murals depict mostly naked prisoners with bleeding fingertips. One prisoner is subjugated by a ruler grabbing his hair. Note that some of the men presiding over the ritualized torture or wearing jaguar pelts (At Catalhoyuk, Turkey, there are murals with men wearing leopard skins).

Depiction of Lady K’ab’al Xook practicing auto-sacrifice by pulling a rope through her tongue. Yaxchilán lintel 24 by Rafael Torres is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Writing

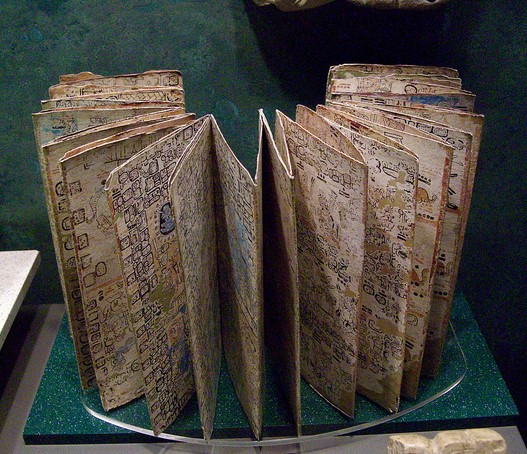

True writing systems indicate the sounds and words of a language, not just a general idea. The term ideographs are sometimes used to refer to image that conveys some generic meaning but are NOT symbols that stand for the sounds of language. The Maya had the most complex writing system in all of Mesoamerica, which was the only area in the New World to have written. And they wrote on everything they could get their hands on, from stone stelae (upright stone monuments), wooden door lintels, pottery, murals, cave walls, carved jades, shells, and other precious objects. The glyphic stairway at Copan, Honduras, contains more than 2,000 glyphs, the longest known Maya text. The Maya also had bark paper books called codices (singular codex). Codices are screen-fold books of bark paper bound with deerskin. These mainly contain astronomical and calendrical information. Some 15,000 examples of Classic Maya writing have been discovered from monuments, pottery, tombs, and other sources. All but three codices were burned by Spanish Bishop Diego de Landa:

We found a large number of books of these characters, and as they contained nothing in which there were not to be seen superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree and which caused them much affliction.

Religious or ideological zealotry has not been good for the preservation of ancient remains. In AD 397 Cyril and his monk army destroyed the Memphis Serapeum along with other ancient Egyptian temples. More recently, the Taliban destroyed the Bayamin Buddhas.

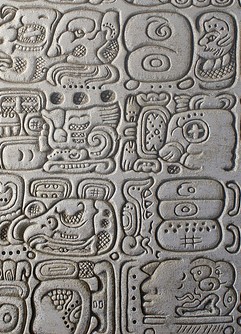

Much of the Mayan writing on monuments such as stelae is political propaganda, used to legitimize a king’s right to rule. Maya stelae, or upright stone monuments, recorded births, ascensions, conquests, marriages and alliances, sacrifices, deaths of rulers as part of this political aggrandizement. Maya’s writing was a specialized craft. The Maya scribe was an important and respected professional, with a noble lineage. The Ah k’u hun was the chief scribe or keeper of the Holy Books or Royal Librarian. It is thought that the general populace was illiterate and that reading and writing were the privileges of the elite. Classic Maya texts were written in a courtly Mayan language, functioning somewhat like Latin in Medieval Europe. The Maya did not use an alphabet, with each letter representing a small unit of sound. Instead, they used glyphs that represented whole words or syllables (clusters of sound).

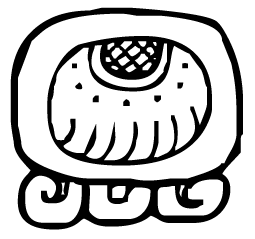

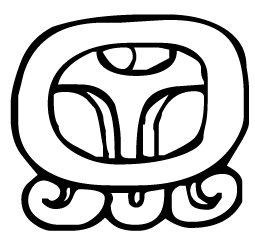

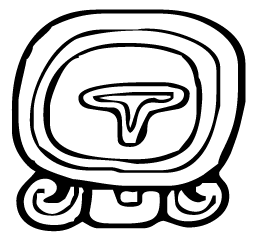

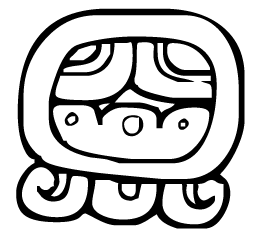

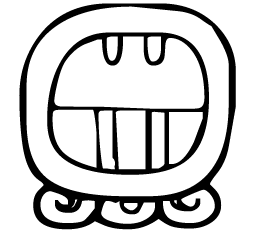

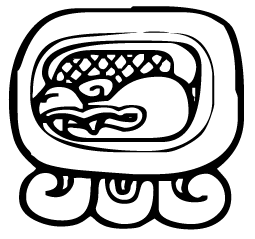

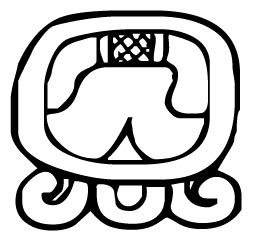

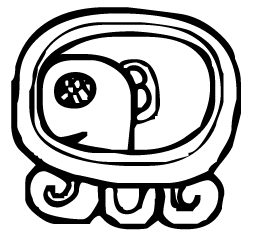

Maya glyphs. “Codex” by Pietro Izzo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND-SA 2.0

Maya Codex. “Los Codices Maya” by Dave Cooksey is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND-SA

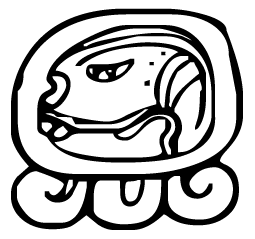

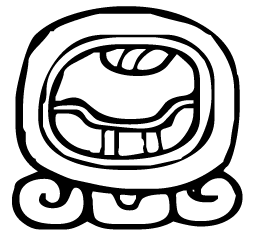

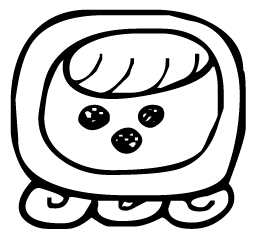

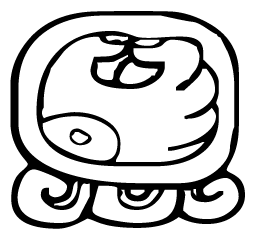

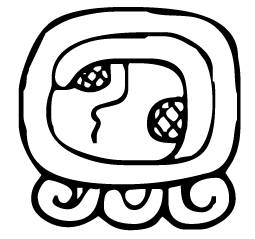

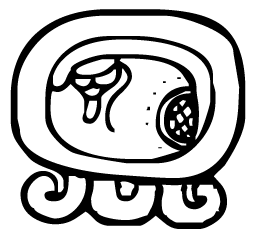

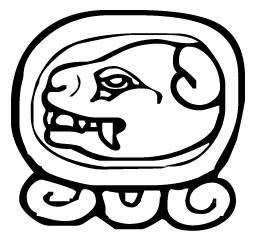

Mayan art and writing were not completely separate. Indeed, the word for writing, tz’ihb, refers also to painting. Maya art contains densely coded information and incorporates glyphs into the design. The Maya logogram for “baby” looks like a baby on its back In the depiction of Lord Pacal on his sarcophagus, we see that he is in the same position as he is reborn as the lightning god. Maya art also uses glyphs or abbreviated glyphs to identify colors, material, smell, shininess, and so forth in the depiction. For example, the Maya glyph for wood is. We can see parts of this glyph on canoes, trees, and other wooden objects depicted in Maya art. Specific gods can also be recognized by their earspools, headdresses, paraphernalia, and body markings. Chahk, the rain god, is often depicted with scales and an ax, usually in the act of chopping a baby jaguar.

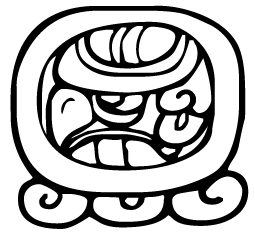

The Maya Rain God Chahk.

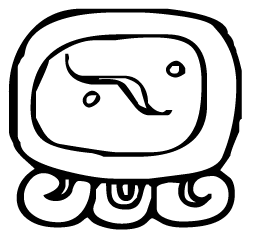

Maya maize god as scribe. Note the shell used to hold ink. Public domain.

Mesoamerican Ballgame

Before there was the Olympics, there was the Mesoamerican ballgame—the ultimate team sport. The Classic Maya and other Mesoamerican cultures discovered that the extract of the rubber tree could be made into a very bouncy ball by adding juice from the morning glory plant. A few balls have survived to this day and many are depicted on figurines. The Mesoamerican ballgame found throughout Mesoamerica, and depiction occurs on murals and statuary.

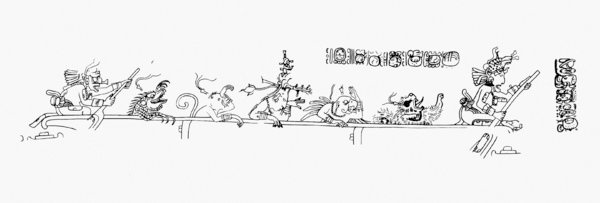

The players wore a yoke made of cloth, wood, or leather around their mid-section for protection from the hardball decorated with a hacha. The uniform and rules varied by culture. The Mesoamerican ballcourt was built of limestone masonry like temple monuments and painted. Classic Maya ballcourts were in the shape of an “I”, with the endzones the top and bottom of the “I”. The “benches” at the base of ballcourts were decorated with scenes of human sacrifice. The ballgame was not just a sporting event but a religious one as well. The losers, at least in some cases, appear to have been sacrificed. Stone relief at El Tajin in Veracruz depicts a ballplayer being sacrificed by having his heart cut out. At the popular honeymoon destination of Chichen Itza, ballplayers are depicted as being decapitated with a large obsidian knife.

Chocolate

Cacao, (from kakawa, a Mayan word) from which chocolate derives, was a precious commodity consumed mostly by nobles and the seeds were even used as a form of currency. Chocolate was usually consumed in liquid form. There appears to have been a number of different Maya recipes for liquid chocolate. Liquid chocolate was poured between cylinder vessels to produce a froth, the most delicious part of the drink. The process of producing chocolate from cacao seeds is quite elaborate. Cacao pods contain a sweet white substance in addition to the cacao seeds. The seeds must be fermented in the sweet white substance for a few days. The seeds are then roasted and crushed to make chocolate liquor. Not all cacao is the same, but the variety that grows in the Maya region still produces the best-tasting chocolate today. Milk and sugar weren’t added to chocolate until after the Spanish arrived.

Calendars

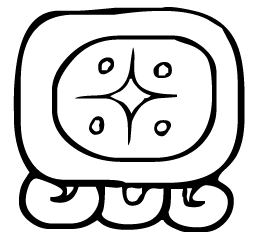

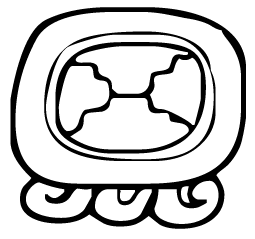

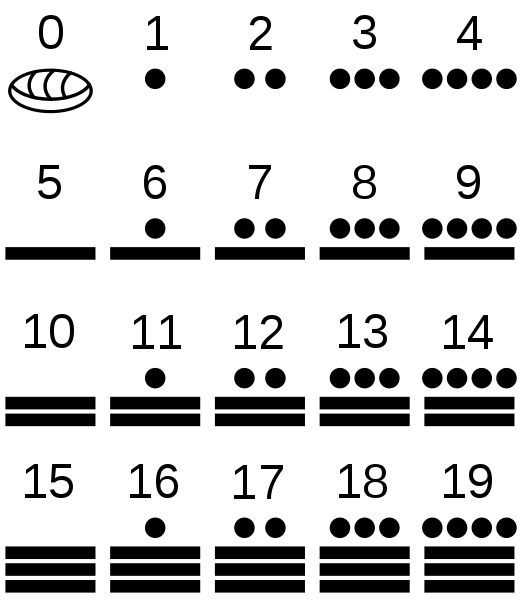

The Maya were astronomers in the sense that they kept track of the cycles of the moon, sun, Venus, and stars. They used the cycles to make future predictions; That is to say, astrology. The Maya also had several ways of tracking time, not unlike archaeologists. Perhaps the one that most people are familiar with is the Long Count, which was used for tracking very long time periods of time. The Maya invented the concept of zero and used a symbol to represent zero mathematically, which facilitated the manipulation of large numbers. The Long Count is basically a count of days forward from a base date, specifically 3114 B.C.E. in the Gregorian calendar. The base date is very much like A.D. (Anno Domini) or C.E. (Current Era). We also have rotating cycles, seven days named after Norse gods with months named after Roman gods and emperors. A Long Count date appears at the beginning of every Maya monumental writing. Mayan numbers are very simple. A dot means “one” and a bar means “five”. Two bars mean “ten”, and so on. The Maya did not have other units of time that are equivalent to ours, however. There was no 7-day week for example. Instead, they carved up time using 20 as a base. Here is how the Maya organized time in the Long Count:

Kin= 1 day

Uinal= 20 days

Tun=360 days

Katun= 20 tuns (7,200 days, about 19.7 years)

Baktun= 400 katuns (144,000 days, about 394 years)

Long Count dates are often written like this in English: 13.0.0.5.10. However, the Maya wrote numbers vertically with the largest unit at the top and the smallest at the bottom, similar to the familiar thousands, hundreds, tens, ones, system. Now you can see why it is called the Long Count. It was the Long Count that set off a frenzy of panic in some circles in late 2012. That was the date for the Long Count cycle to come to an end. After 13 baktuns, the Long Count “turns over” and starts again, or according to some, the world ends. Given that the Maya themselves inscribed dates beyond the end of the 13th baktun it appears that even the ancient Maya didn’t think it was cause for alarm. But wait, that’s not all. The Maya had two other calendars at play. The Maya had a 260-day calendar called the Tzolk’in and a 365-day solar calendar called the Haab. The Tzolk’in was a ceremonial calendar that marked important ritual days, which continues to be used to this day. The Haab was the civil calendar, used to keep track of days in accordance with the changing seasons. The combination of the two calendars called the Calendar Round, returned to its starting point, 4 Ahau 8 Cumku, every 52 years. (The smallest number that can be divided evenly by 260 and 365 is 18,980, which equals 52 years). This was an occasion for building monuments, ceremonies, and celebrations.

The Tzolk’in can be visualized by two rotating wheels. Wheel 1 has thirteen numbers and Wheel 2 has 20 named characters. The combination of the first number and a day won’t repeat for 260 days. The Haab is somewhat more familiar having months. There are 18 months of 20 days each, plus one month of 5 days for a total of 365 days. That last awkward month of only 5 days was said to be bad luck and may have even gotten you sacrificed. If you want to know when you were born according to the Maya calendars try this link The Maya had still other forms of tracking time. The Katun cycle was particularly important (about every 20 years) and was a cause for monument building and celebration.

Collapse?

The Maya “collapse” occurred in the 700s. most archaeologists do not like to use the word collapse, especially in the Maya case, because the Maya continued in other areas. Nonetheless, something different began to happen around the 700s. During this time monument building began to decline along with hieroglyphic texts and some long-distance trade contacts ended, and warfare increased. And yet, because the environment was so variable and the kingdoms so diverse, the collapse happened differently in different areas. Some areas were depopulated, others built fortifications, some areas even flourished during this time period while others saw a slow decline. The phenomenon that universally disappeared during the collapse was the idea of the holy lord, the K’uhul Ajaw, with the associated stelae and tomb temples. In this way, the word “collapse” does not necessarily mean the disappearance of a people, but the disappearance of a particular ideological system.

Some have argued that the system of the holy lord was inherently unstable and the constant competition for power, costly displays, and warfare were ultimately unsustainable. Others point to climate change and population sizes as being a major factor in the collapse. Some have argued for a disconnect between climatic, demographic and ideological factors that could no longer be sustained. The Maya passion for plastering public monuments is a good example. Lime plaster, so important in the maintenance of the theater state of the K’uhul Ajaw, required burning of limestone, which is turn required fuel. In this way, the material required to support the pageantry of Maya kingdoms may have directly contributed to environmental degradation in the form of rainforest clearing and subsequent erosion. The pageantry of the K’uhul Ajaw was incompatible with the delicate nature of the rainforest. Research continues today to try to understand how the collapse of the K’uhul Ajaw unfolded in different regions.

Acid Rain and Maya Monuments

Oil refineries and tour busses produce chemicals that can lead to acid rain in the Maya region today. The oil refineries produce nitrogen and sulfur oxides (Nox and Sox), eventually producing sulfuric and nitric acid as they react with water and oxygen in the air. Pemex, which is government-run, owns the oilfields, which are economically important to the region. The Maya constructed their monuments from limestone (CaCo3) and like corals in the ocean and subject to deterioration from acid rain. The acid rain can turn the limestone or lime stucco into gypsum, which flakes and crumbles off. In some cases, it produces a “black scab”. Removing the scabs also tends to remove the underlying paint and stucco. In other areas that are rarely visited, sites may be more protected by the forest from acid rain. While the sculptures at the Parthenon were removed to an indoor location (and replaced by replicas outside), the giant Maya temple monuments cannot be sheltered so easily.

Recommended Readings

Demarest, Arthur 2004 Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Cambridge. Coe, Sophie D. and Michael D. Coe 1996 The True History of Chocolate. Thames and Hudson. i Arthur Demarest, Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Cambridge. 2004, P. 297 ii Vessel with Mythological Scene [Guatemala; Maya]” (1978.412.206) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: the metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1978.412.206. (October).