Engaging with Research

Carrying out and communicating research is an integral part of professional communication. This chapter explores many of the considerations of sound, ethical research, including:

- Creating Common Types of Research Reports & Documents

- Conducting Research

- Evaluating Sources

- Documenting Sources

- Writing About Research

Learning about technical writing and workplace communication is the overall goal for this course. Technical writing, in either the workplace or in academia, requires a writer to be persuasive and accurate. Persuasion and accuracy are often developed by implementing research and data into your writing. In this course, you are required to create a proposal and persuade your audience that your idea is a strong option, and, in order to support your ideas, you will need to complete research, so this chapter will focus on how, as a student, you can investigate and solve a problem by researching the problem, reporting the data, and offering solutions.

A proposal begins with a problem that you’re interested in solving; here is an overview of the proposal writing process in this course:

- First, you will identify a problem in a workplace (either where you currently work or in a hypothetical workplace).

- Second, you will brainstorm possible solutions to the problem.

- Third, you will gather external research that explains why the change or suggestion you are making supports the proposal.

- Fourth, you will compile the findings from your investigation into a Feasibility Report or Proposal on solving the problem.

- Fifth and last, you will create a presentation that outlines your research solutions.

Remember that this is not a typical research paper where you research an issue and simply report the research. Therefore, do not choose issues like changing laws, fighting wars, drug usage, or global warming, among others. While these are important issues and you can certainly offer solutions, they are too broad for you to have a personal effect on their changing. These topics would fit the definition of writing a typical research paper where you research an issue and write a paper that reports your findings.

Your problem for this course needs to be a practical problem, one in which you will have a personal effect on changing. You can create a scenario and work from that. We will develop and narrow our problems together as the course progresses.

Researching Effectively

Being a good technical writer also means being an effective researcher. This includes finding accurate information from trustworthy sources, seamlessly incorporating the information into a document, and knowing how to cite, or give credit, to the original source. You will begin applying these research skills as you begin the research process for your final proposal assignment.

The following video is a great overview of the most common college level research strategies. This video is short and provides the necessary information about how to start your research.

Required Citation

Learning how to cite your research is an important part of the research process. The required citation for your proposal is the American Psychological Association (APA). Whenever you are asked to research and then present your research in technical documents, it is imperative that you give credit to others when you use or reference their ideas. We do this by documenting sources.

There are different ways to format when documenting research. Most students have completed research papers using Modern Language Association (MLA) since this is what is most often used by English teachers. However, in this course, we use APA because it applies to business writing. This being said, MLA and APA are simply ways to format research, so don’t let the task of research be daunting. When documenting sources for this class, you don’t have to memorize how to cite a book vs. an online article; you simply have to know how to use our class textbook or an online resource to cite your information.

What to Document

There are different ways to decide whether information should be cited in the body of your paper or on the references page. Researchers document anything that is quoted, paraphrased, or summarized; this includes a phrase, sentence, paragraph, or longer section taken from a source. Make sure to place quotation marks around the material borrowed verbatim to show that it is the exact phrasing used from a source.

Paraphrased or summarized information also needs to be documented. These are ideas taken from someone else that you put into your own words. The language used needs to be original and fresh. The writer cannot simply switch a sentence around and change a few words. The writer must completely put the source’s ideas into the writer’s own words. Quotation marks are not used when you paraphrase, but the writer does need to include a textual citation to give credit to the original source.

Any visuals, graphics, and pictures taken from anywhere need to be cited. Often, individuals think they can snag an image from Google and copy and paste it into a paper or presentation without citing it; this is plagiarism. Anything that was not created in whole by the writer needs to be cited. In short, always give credit to another person’s ideas or work; never pass them off as your own.

How Citation Works

We will cover the process of creating citations in more depth in Chapter 13, but as you begin researching it is important to remember that when you take information from another source, you must give credit by:

- Using textual citations. Cite the source within the text of the document to show which section of your document was taken from the source. This is called a “textual citation,” and it is placed after the information the writer borrowed and consists of a few pieces of information in parentheses that allows the reader to locate the full source in the list of references at the end of the document. Textual citations in APA usually consist of the author’s last name, a comma, the year it was published, another comma, and a page number (if there is one). These are put within parentheses.

Examples of Textual Citations:

- This issue was identified and revealed more than 50 years ago (Abramson, 2000).

or

- Abramson (2000) identified and revealed this issue more than 50 years ago.

or

- The greenhouse effect is a controversial one that some people are not taking serious (Smith, 2014, p. 56).

- Linking every textual citation to the list of references at the end of the document. Create a references page at the end of your paper. Textual citations correspond with the bibliographic information listed in the references section of the paper. The textual citations must match the list of references. You never have a textual citation that isn’t covered in the list of references, and you usually don’t have a source cited in the list of reference that doesn’t have a textual citation. They go together. Consider them a couple.

Example of a reference at end of document:

References

Abramson, M. (2000). Communication mythes. Baltimore, General Press.

We will go over citation and avoiding plagiarism in future sections, but this is a good starting point as you begin researching for your final proposal assignment. The following video provides a quick overview of how textual citations work with reference pages:

Additional Resources

Purdue Owl Website

For additional tips and samples of APA textual citations, visit the Purdue OWL writing center: Purdue OWL: APA Formatting. This website works well because it is reputable, and it can be accessed when this class ends. In fact, many colleges and universities regularly use it. Save this site on your computer, and use the links on the left side of it to create textual citations and a list of references at the end of a document.

American Psychological Association Website

This is another site that can help with APA: APA: American Psychological Association. It is the official APA website.

Adapted and synthesized from three texts:

- “Chapter 5 R” of ENGL 145: Technical and Report Writing, 2017, used according to creative commons CC-BY 4.0

- Engaging With Research by Lynn Hall and Leah Wahlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Technical Writing. Authored by: Dr. Elizabeth Lohman. Provided by: Tidewater Community College. Located at: http://www.tcc.edu. Project: Z Degree Program. License: CC-BY 4.0

Strategies for Conducting Research

Now that you have a general understanding about the necessity of citing your research, it’s time to start locating research. As a CNM student, you have access to many great resources including the CNM Library and CNM Librarians. These resources cannot be understated as you begin the research process. The following sections will introduce you to the different resources you can utilize as you begin your own research process.

Getting to Know Your Library

In the 21st century, we have more information and knowledge instantaneously at our fingertips than could have been imagined 100, 50, or even 30 years ago. Figuring out how to wade through all of that information can be daunting. Research is one way we can make sense of and discuss all the information available to us. Research is the basis for strong and persuasive communication because it helps us understand what others have said, done, and written about a particular topic or issue.

In the modern library, whose shelves could be wooden, metal, or electronic, we need to school ourselves in best practices to ensure we efficiently access the best material from these shelves. We do this by overcoming the attitude that the library is a foreign country, by rapidly understanding distinctions among resources, and by using search engines effectively.

To research in the modern library, follow these basic practices:

- Take a tour. Whether self-guided, human-led, or virtual, a tour curbs the fundamental confusion about where you are within a library, which can make all the difference when you are chasing down a particular source in a hurry. A simple tour will also expose you to the different forms and locations of library resources, such as help desks, shelves for current periodicals, and reference shelves.

- Plan ahead. Especially when working on a sizeable project, it is unrealistic to expect that all the resources you need will be immediately available. You must give yourself time to physically track down resources, recall material that is checked out, research archived material, request interlibrary loans, or deal with the inevitable limitations of resources that you find.

- Recognize how libraries work together. Especially at a large college, you can encounter multiple, specialized libraries within one system, and you have access to interlibrary loan (allowing you to borrow books from other libraries). No library is or even tries to be a “one-stop shop.”

- View the library webpages as a time-saving device. Beyond their obvious aid as a research tool, library webpages are typically set up to save you time. You can usually reserve books online, renew books online, and even suggest books for purchase or e-mail specific questions to a librarian.

- When you find a hard copy of a resource, browse the nearby shelves. Frequently, while standing among the library shelves, I have discovered some of the best resources simply by looking through the related books near the one I was originally seeking. Such serendipitous, productive discovery is a lot more likely to happen at the library shelves than online.

- Do not fear the human. When in doubt, ask a real person who is paid and usually excited to help you.

Discerning Distinctions Among Resources

When choosing the best resources for a particular task, you improve and narrow your search by assessing source quality and establishing a good fit between the level of source information required and the circumstances for which you are writing. A good starting point is determining whether a resource is scholarly or popular, whether its material is more anecdotal or research-based, and whether the author’s tone is subjective or factual. When discerning which sources best fit the task at hand, keep in mind these guidelines:

- You can rapidly determine the quality and usefulness of a source without fully reading it. Consider such issues as its level of language use, its context (whether published as a single work or as part of a collection), and the sources that it cites. Popular material is often short, not technically oriented, and topical. Scholarly work tends to be longer and more structured, more technical, and concerned with adding to a body of academic work rather than just standing alone.

- The best academic resources are usually journals that are “peer-reviewed” or “refereed” (the two terms are used almost interchangeably). This means that the journal editor has had other authorities critique and approve articles that the journal publishes. Practices vary about how this review takes place, but such review affords a level of quality that other resources might not possess. If the journal is online, you can try to determine if it is peer-reviewed by reading its root pages, but the surest way is to find a print version of the journal and look at its “Information for Authors” page, typically appearing in the back or front of the journal.

- When seeking print journal articles, narrow your search by using abstracts and indexes available on your library shelves. This helps you find resources across disciplines, and abstracts and indexes provide a form of quality control by listing established journals.

What is Research?

Research begins with questions. Before you begin to find sources, you must determine what you already know and what you hope to learn. Do you want first-person reflections and commentary? Statistics and facts? News reports? Scientific analyses? History?

For example, if you are interested in a recent piece of legislation then you would want to locate the full-text of the bill as well as commentary about the legislation from reliable news organizations such as The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times. If you are interested in statistics about the U.S. population, you might go to the U.S. Census Bureau or the Pew Research Center. Perhaps you are interested in the experiences of veterans returning from active duty. In this case you may turn to blogs or op-eds written by vets, official U.S. military records from agencies such as the Department of Defense, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, or organizations such as the RAND Corporation.

Primary vs Secondary Research

There are two basic kinds of research—primary and secondary. Often, primary and secondary research are used together.

Primary research is often first-person accounts and can be useful when you are researching a local issue that may not have been addressed previously and/or have little published research available. You may also use primary research to supplement, confirm, or challenge national or regional trends with local information. Primary research can include:

- Interviews

- Surveys

- Questionnaires

- Observations and analysis

- Ethnography (the study and description of people, cultures, and customs)

Secondary research is what many students are most familiar with as it generally requires searching libraries and other research institutions’ holdings. Secondary research requires that you read others’ published studies and research in order to learn more about your topic, determine what others have written and said, and then develop a conclusion about your ideas on the topic, in light of what others have done and said. Some examples of source types that might be used in secondary research include:

- Academic, scientific, and technical journal articles

- Governmental reports

- Raw data and statistics

- Trade and professional organization data

Primary and secondary research often work together to develop persuasive arguments. Let’s say, for example, you are interested in using STEM knowledge to improve the quality of life for the homeless population in Columbus, Ohio. The most successful project would use both secondary and primary research. First, the secondary research will help establish best or common practices, trends, statistics, and current research about homelessness both broadly in the U.S. and state, and more narrowly in the county and city.

Your brainstorming would likely lead to questions regarding the following:

- Issues facing homelessness and combating homelessness in the U.S.

- Issues concerning the homeless population and demographics for Columbus, Ohio

- Services currently available for the homeless in Columbus

- Services available in other cities and the state

The above information would likely be available through secondary research sources. Useful information would likely be available through city and state government agencies such as U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; local and national homeless advocacy groups such as the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio, Columbus Coalition for the Homeless, National Alliance to End Homelessness, and the National Coalition for the Homeless. You would also need to search relevant research databases in subject areas such as engineering, sociology and social work, and government documents.

Additionally, primary research, such as interviews or surveys can provide more in-depth and local bent to the numbers and details provided in secondary sources. Some examples of groups to interview or survey include local homeless advocates; shelter and outreach employees and volunteers; people currently or previously experiencing homelessness, such as the vendors or writers for the street newspaper Street Speech; researchers or university-affiliated groups, such as OSU’s STAR House, that conducts, compiles, and applies research on homelessness. Often, the strongest research blends primary and secondary research.

Where do I begin?

Research is about questions. In the beginning the questions are focused on helping you determine a topic and types of information and sources; later in the research process, the questions are focused on expanding and supporting your ideas and claims as well as helping you stay focused on the specific rhetorical situation of your project.

Questions to get started

- What is my timeline for the project? You will likely want to set personal deadlines in addition to your instructor’s deadlines.

- What do I want to know or learn about? This helps you determine scope or the limits of your research. If you’re writing a dissertation or thesis, then your scope will generally be larger because those types of projects are often 100+ pages. For a term paper, the scope will be more narrow. For example, if you’re interested in NASA funding and research, you may limit yourself to the past 10-15 years because NASA has been around for nearly 60 years. Further, you may limit your focus to research that has transitioned into technologies or resources used outside of NASA and the space program.

- What do I already know about this topic?

- What biases might I have about this topic? How might I combat these biases?

Questions to determine methodology

- Where might I find useful, reliable information about this topic? For academic and workplace research, you can generally focus on library, technical, scientific, and governmental resources. It is fine if you are not quite sure exactly where you should look; your instructor or college librarian should be able to help you determine some places that would be appropriate.

- Will I need to perform primary research, secondary research, or both?

Next you will have to develop a research question. By this point you should have a general idea of your topic and some general ideas of where you might find this information.

Research Questions

Research questions generally form the basis for your project’s main argument. Research questions are not about facts, but are about opinions, ideas, or concerns.

Which of these is a research question?

- What is NASA’s budget for 2016?

- What is the impact of NASA’s budget on scientific breakthroughs and contributions to non-space-related fields?

The former can be answered quickly and easily (NASA’s 2016 budget was about $19.3 billion), but the latter requires detailed analysis of multiple sources and considerations of various opinions and facts. The second question requires critical thinking as well; therefore, response two is a research question.

Where do I look?

In the 21st century, we generally turn to the internet when we have a question. For technical, scientific, and academic research, we can still turn to the internet, but where we visit changes. We will discuss a few different places where you can perform research including Google, Google Scholar, and as a CNM student, you can reference the CNM library at https://www.cnm.edu/depts/libraries.

Google.com and Scholar.google.com

The default research site for most students tends to be Google. Google can be a great starting place for a variety of research. You can use Google to find news articles and other popular sources such as magazine articles and blog posts. You can use Google to discover keywords, alternative terms, and relevant professional, for-profit, and non-profit businesses and organizations. The most important idea to remember about using Google is that search results are organized by popularity, not by accuracy. Further, because Google customizes search results based on a user’s search history, searches performed by different people or on different browsers may provide slightly different results.

For many technical, scientific, and scholarly topics, Google will not provide access to the appropriate and necessary types of sources and information. Google Scholar, however, searches only academic and scientific journals, books, patents, and governmental and legal documents. This means the results will be more technical and scholarly, and, therefore, more appropriate for much of the research you will be expected to perform as a student. Though Google Scholar will show academic and technical results, that does not mean that you will have access to the full-text documents. Many of the sources that appear on Google Scholar are from databases, publishers, or libraries, which means that they are often behind paywalls or password-protected. In many cases, this means you will have to turn to a college, university, or other library for access, and if CNM college does not have access to a specific journal, you can request an article or book through Interlibrary Loan or ILL. You have to activate your ILL account before requesting a text that the library does not own. Google Scholar can help streamline your searching, but you can turn to the expertise of CNM librarians to help you access those items for free.

College and University Libraries

Library resources such as databases, peer-reviewed journals, and books are generally the best bet for accurate and more technical information. A Google search might yield millions and millions of results and a Google Scholar search may yield tens or hundreds of thousands of results, but a library search will generally turn up only a couple thousands, hundreds, or even dozens of results. You may think, “Isn’t fewer results a bad thing? Doesn’t that mean limiting the possibilities for the project?” The quick answers are yes, fewer results means fewer options for your project, but no, this does not mean using the library limits the possibilities for a project.

Overall, library resources are more tightly controlled and vetted. Anyone can create a blog or website and post information, regardless of the accuracy or usefulness of the information. Library resources, in contrast, have generally gone through rigorous processes and revisions before publication. For example, academic and scientific journals have a review system in place—whether a peer-review process or an editorial board—both feature panels of people with expertise in the areas under consideration. Publishers for books also feature editorial boards who determine the usefulness and accuracy of information. Of course, this does not mean that every peer-reviewed journal article or book is 100% accurate and useful all of the time. Biases still exist, and many commonly accepted facts change over time with more research and analysis. Overall the process for these types of publications require that multiple people read and comment on the work, providing some checks and balances that are not present for general internet sources.

So what are common types of library sources?

- Databases: databases are specialized search service that provide access to sources such as academic and scientific journals, newspapers, and magazines. An example of a database would be Academic Search Complete.

- Journals: journals are specialized publications focused on an often narrow topic or field. For example, Computers & Composition is a peer-reviewed journal focused on the intersection of computers, technology, and composition (i.e. writing) classrooms. Another example is the Journal of Bioengineering & Biomedical Science.

- Books: also called monographs, books generally cover topics in more depth than can be done in a journal article. Sometimes books will contain contributions from multiple authors, with each chapter authored separately.

- Various media: depending on the library, you may have access to a range of media, including documentaries, videos, audio recordings, and more. Some libraries offer streaming media that you can watch directly on the library website without having to download any files.

Consulting a Reference Librarian

Sifting through library stacks and database search results to find the information you need can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack. If you are not sure how you should begin your search, or if it is yielding too many or too few results, you are not alone. Many students find this process challenging, although it does get easier with experience. One way to learn better search strategies is to consult a reference librarian.

Reference librarians are intimately familiar with the systems libraries use to organize and classify information and are skilled at assisting searchers find just what they are looking for, and helping you improve your research skills at the same time. The link to CNM’s library home page can be found below.

Research Librarians at CNM can be found on six campuses. Table 1: “CNM Library Contact Information” lists contact information for each branch.

|

Campus |

Contact |

|

Main Campus |

(505) 224-3274 |

|

Westside Campus |

(505) 224-4953 |

|

South Valley Campus |

(505) 224-5016 |

|

Montoya Campus |

(505) 224-5721 |

|

ATC Learning Commons |

(505) 224-5152 |

|

Rio Rancho Campus |

(505) 224-4953 |

CNM’s librarians can help you locate a particular book in the library stacks, steer you toward useful reference works, provide tips on how to search databases and electronic research tools, or help you break down a complex research question. Take the time to see what resources you can find on your own, but if you encounter difficulties or just want to learn more, ask a librarian. CNM’s librarians can be accessed via an online chat function under “Get Help” on the library homepage or you can email reference librarians at [email protected].

How do I perform a search?

Research is not a linear process. Research requires a back and forth between sources, your ideas and analysis, and the rhetorical situation for your research. The research process is a bit like an eye exam. The doctor makes a best guess for the most appropriate lens strength, and then adjusts the lenses from there. Sometimes the first option is the best and most appropriate; sometimes it takes a few tries with several different options before finding the best one for you and your situation.

Once you decide on a general topic, you will need to determine keywords that you can use to search different resources. The importance of this step cannot be underrated; having strong key terms will help you create a more successful research experience. Databases categorize information using specific terms, and the keywords you use will change the results you receive. For example, databases like Academic Search Complete or Academic OneFile categorize articles about the death penalty using the term capital punishment. If you have search for a topic that you believe has been written and published about, brainstorm synonyms for the keywords you use to yield more results.

Adapted and synthesized from three texts:

- “Chapter 5 Using Sources” of Style for Students Online: Effective Technical Writing in the Information Age, used according to creative common (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US)

- “Gathering Reliable Information” from Introduction to College Writing by Jennifer Schaller and Tammy Wolf, CC-BY 4.0

- “Strategies for Conducting Research” by Lynn Hall and Leah Wahlin is licensed under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 license, except where otherwise noted.

Evaluating Types of Sources

The different types of sources you will consult are written for distinct purposes and with different audiences in mind. This accounts for other differences, such as the following:

- How thoroughly the writers cover a given topic.

- How carefully the writers’ research and document facts.

- How editors review the work.

- What biases or agendas affect the content.

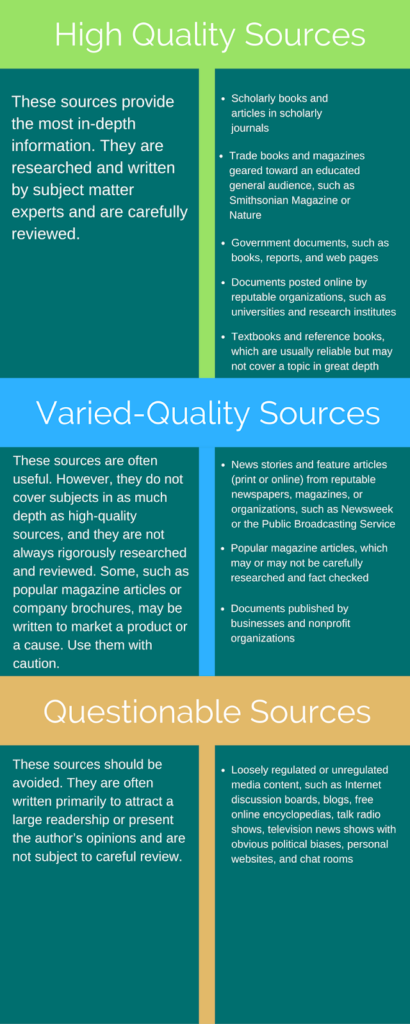

A journal article written for an academic audience for the purpose of expanding scholarship in a given field will take an approach quite different from a magazine feature written to inform a general audience. Textbooks, hard news articles, and websites approach a subject from different angles as well. To some extent, the type of source provides clues about its overall depth and reliability. Table 2: “Source Rankings” ranks different source types.

Evaluating Credibility and Reputability

Even when you are using a type of source that is generally reliable, you will still need to evaluate the author’s credibility and the publication itself on an individual basis. To examine the author’s credibility or ethos—that is, how much you can believe of what the author has to say—review their credentials. What career experience or academic study shows that the author has the expertise to write about this topic?

Keep in mind that expertise in one field is no guarantee of expertise in another, unrelated area. For instance, an author may have an advanced degree in physiology, but this credential is not a valid qualification for writing about psychology. Check credentials carefully.

Just as important as the author’s credibility is the publication’s overall reputability. Reputability refers to a source’s standing and reputation as a respectable, reliable source of information. An established and well-known newspaper, such as The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal, is more reputable than a college newspaper put out by comparatively inexperienced students. Furthermore, a website that is maintained by a well-known, respected organization and regularly updated is more reputable than one created by an unknown author or group.

If you are using articles from scholarly journals, you can check databases that keep count of how many times each article has been cited in other articles. This can be a rough indication of the article’s quality or, at the very least, of its influence and reputation among other scholars.

Checking for Biases and Hidden Agendas

Whenever you consult a source, always think carefully about the author’s or authors’ purpose in presenting the information. Few sources present facts completely objectively. In some cases, the source’s content and tone are significantly influenced by biases or hidden agendas.

Bias refers to favoritism or prejudice toward a particular person or group. For instance, an author may be biased against a certain political party and present information in a way that subtly—or not so subtly—makes that organization look bad. Bias can lead an author to present facts selectively, edit quotations to misrepresent someone’s words, and distort information.

Hidden agendas are goals that are not immediately obvious but influence how an author presents the facts. For instance, an article about the role of beef in a healthy diet would be questionable if it were written by a representative of the beef industry—or by the president of an animal-rights organization. In both cases, the author would likely have a hidden agenda.

Using Current Sources

Be sure to seek out sources that are current or up to date. Depending on the topic, sources may become outdated relatively soon after publication, or they may remain useful for years. For instance, online social networking sites have evolved rapidly over the past few years. An article published in 2002 about this topic will not provide current information. On the other hand, a research paper on elementary education practices might refer to studies published decades ago by influential child psychologists and are still relevant.

When using websites for research, check to see when the site was last updated. Many sites publish this information on the homepage, and some, such as news sites, are updated daily or weekly. Many non-functioning links are a sign that a website is not regularly updated. Do not be afraid to ask your professor for suggestions if you find that many of your most relevant sources are not especially reliable—or that the most reliable sources are not relevant.

Evaluating Overall Quality by Asking Questions

When you evaluate a source, consider the criteria previously discussed as well as your overall impressions of its quality. Read carefully, and notice how well the author presents and supports his or her statements. Stay actively engaged—do not simply accept an author’s words as truth. Ask questions to determine each source’s value. See Table 3: Source Evaluation Checklist below for a list of evaluative criteria.

-

Is the type of source appropriate for my purpose? Is it a high-quality source or one that needs to be looked at more critically?

-

Can I establish that the author is credible and the publication is reputable?

-

Does the author support ideas with specific facts and details that are carefully documented? Is the source of the author’s information clear? (When you use secondary sources, look for sources that are not too removed from primary research.)

-

Does the source include any factual errors or instances of faulty logic?

-

Does the author leave out any information that I would expect to see in a discussion of this topic?

-

Do the author’s conclusions logically follow from the evidence that is presented? Can I see how the author got from one point to another?

-

Is the writing clear and organized, and is it free from errors, clichés, and empty buzzwords? Is the tone objective, balanced, and reasonable? (Be on the lookout for extreme, emotionally charged language.)

- Are there any obvious biases or agendas? Based on what I know about the author, are there likely to be any hidden agendas?

-

Are graphics informative, useful, and easy to understand? Are websites organized, easy to navigate, and free of clutter like flashing ads and unnecessary sound effects?

- Is the source contradicted by information found in other sources? (If so, it is possible that your sources are presenting similar information but taking different perspectives, which requires you to think carefully about which sources you find more convincing and why. Be suspicious, however, of any source that presents facts that you cannot confirm elsewhere.)

Adapted and synthesized from two sources:

- “Chapter 5 Using Sources” of Style for Students Online: Effective Technical Writing in the Information Age, used according to creative common (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US)

- “Chapter 11” of Successful Writing, 2012, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 3.0