Part 4: Chapter 23.2

Although at its most basic level a synthesis involves combining two or more summaries, synthesis writing is more difficult than it might at first appear because this combining must be done in a meaningful way and the final essay must generally be thesis-driven. In composition courses, “synthesis” commonly refers to writing about printed texts, drawing together particular themes or traits that you observe in those texts and organizing the material from each text according to those themes or traits. Sometimes you may be asked to synthesize your own ideas, theory, or research with those of the texts you have been assigned. In your other college classes you’ll probably find yourself synthesizing information from graphs and tables, pieces of music, and art works as well. The key to any kind of synthesis is the same.

Synthesis in Every Day Life

Whenever you report to a friend the things several other friends have said about a film or CD you engage in synthesis. People synthesize information naturally to help other see the connections between things they learn; for example, you have probably stored up a mental data bank of the various things you’ve heard about particular professors. If your data bank contains several negative comments, you might synthesize that information and use it to help you decide not to take a class from that particular professor. Synthesis is related to but not the same as classification, division, or comparison and contrast. Instead of attending to categories or finding similarities and differences, synthesizing sources is a matter of pulling them together into some kind of harmony. Synthesis searches for links between materials for the purpose of constructing a thesis or theory.

Synthesis Writing Outside of College

The basic research report (described below as a background synthesis) is very common in the business world. Whether one is proposing to open a new store or expand a product line, the report that must inevitably be written will synthesize information and arrange it by topic rather than by source. Whether you want to present information on child rearing to a new mother, or details about your town to a new resident, you’ll find yourself synthesizing too. And just as in college, the quality and usefulness of your synthesis will depend on your

accuracy and organization.

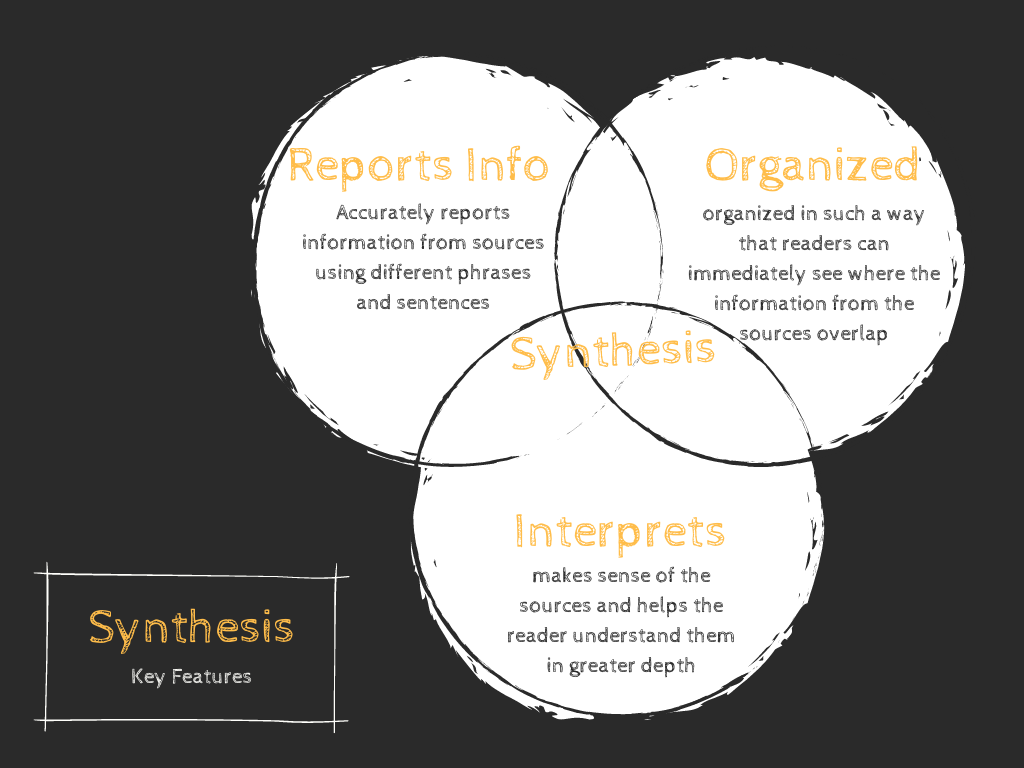

Key Features of a Synthesis

(1) It accurately reports information from the sources using different phrases and sentences;

(2) It is organized in such a way that readers can immediately see where the information from the sources overlap;.

(3) It makes sense of the sources and helps the reader understand them in greater depth.

The Background Synthesis

The background synthesis requires that you bring together background information on a topic and organize it by topic rather than by source. Instructors often assign background syntheses at the early stages of the research process, before students have developed a thesis–and they can be helpful to students conducting large research projects even if they are not assigned. In a background synthesis of Internet information that could help prospective students select a college, for example, one paragraph might discuss residential life and synthesize brief descriptions of the kinds of things students might find out about living on campus (cited of course), another might discuss the academic program, again synthesizing information from the web sites of several colleges, while a third might synthesize information about co-curricular activities. The completed paper would be a wonderful introduction to internet college searching. It contains no thesis, but it does have a purpose: to present the information that is out there in a helpful and logical way. In the process of writing his or her background synthesis, the student explored the sources in a new way and become an expert on the topic. Only when one has reached this degree of expertise is one ready to formulate a thesis. Frequently writers of background synthesis papers develop a thesis before they have finished. In the previous example, the student might notice that no two colleges seem to agree on what constitutes “co-curricular,” and decide to research this question in more depth, perhaps examining trends in higher education and offering an argument about what this newest trend seems to reveal.

A Thesis-driven Synthesis

Sometimes there is very little obvious difference between a background synthesis and a thesis-driven synthesis, especially if the paper answers the question “what information must we know in order to understand this topic, and why?” The answer to that question forms the thesis of the resulting paper, but it may not be a particularly controversial thesis. There may be some debate about what background information is required, or about why, but in

most cases the papers will still seem more like a report than an argument. The difference will be most visible in the topic sentences to each paragraph because instead of simply introducing the material for the paragraph that will follow, they will also link back to the thesis and assert that this information is essential because… On the other hand, all research papers are also synthesis papers in that they combine the information you have found in ways that help readers to see that information and the topic in question in a new way. A research paper with a weak thesis (such as: “media images of women help to shape women’s sense of how they should look”) will organize its findings to show how this is so without having to spend much time discussing other arguments (in this case, other things that also help to shape women’s sense of how they should look). A paper with a strong thesis (such as “the media is the single most important factor in shaping women’s sense of how they should look”) will spend more time discussing arguments that it rejects (in this case, each paragraph will show how the media is more influential than other factors in that particular aspect of women’s sense of how they should look”).

A Synthesis of the Literature

In many upper level social sciences classes you may be asked to begin research papers with a synthesis of the sources. This part of the paper which may be one paragraph or several pages depending on the length of the paper–is similar to the background synthesis. Your primary purpose is to show readers that you are familiar with the field and are thus qualified to offer your own opinions. But your larger purpose is to show that in spite of all this wonderful research, no one has addressed the problem in the way that you intend to in your paper. This gives your synthesis a purpose, and even a thesis of sorts. Because each discipline has specific rules and expectations, you should consult your professor or a guide book for that specific discipline if you are asked to write a review of the literature and aren’t sure how to do it.

Preparing to Write Synthesis

Regardless of whether you are synthesizing information from prose sources, from laboratory data, or from tables and graphs, your preparation for the synthesis will very likely involve comparison. It may involve analysis, as well, along with classification, and division as you work on your organization. Sometimes the wording of your assignment will direct you to what sorts of themes or traits you should look for in your synthesis. At other times, though, you may be assigned two or more sources and told to synthesize them. In such cases you need to formulate your own purpose, and develop your own perspectives and interpretations. A systematic preliminary comparison will help. Begin by summarizing briefly the points, themes, or traits that the texts have in common (you might find summary-outline notes useful here). Explore different ways to organize the information depending on what you find or what you want to demonstrate (see above). You might find it helpful to make several different outlines or plans before you decide which to use. As the most important aspect of a synthesis is its organization, you can’t spend too long on this aspect of your paper!

Writing The Synthesis Essay

A synthesis essay should be organized so that others can understand the sources and evaluate your comprehension of them and their presentation of specific data, themes, etc. The following format works well.

The introduction of a synthesis essay:

I. The introduction (usually one paragraph)

1. Contains a one-sentence statement that sums up the focus of your synthesis.

2. Also introduces the texts to be synthesized:

(i) Gives the title of each source (following the citation guidelines of whatever style

sheet you are using);

(ii) Provides the name of each author;

(ii) Sometimes also provides pertinent background information about the authors,

about the texts to be summarized, or about the general topic from which the

texts are drawn.

The body of a synthesis essay:

I. The introduction (usually one paragraph)

1. Contains a one-sentence statement that sums up the focus of your synthesis.

2. Also introduces the texts to be synthesized:

(i) Gives the title of each source (following the citation guidelines of whatever style

sheet you are using);

(ii) Provides the name of each author;

(ii) Sometimes also provides pertinent background information about the authors,

about the texts to be summarized, or about the general topic from which the

texts are drawn.

This should be organized by theme, point, similarity, or aspect of the topic. Your organization will be determined by the assignment or by the patterns you see in the material you are synthesizing. The organization is the most important part of a synthesis, so try out more than one format.

Individual Paragraphs

1. Begin with a sentence or phrase that informs readers of the topic of the paragraph;

2. Include information from more than one source;

3. Clearly indicate which material comes from which source using lead in phrases and in-text citations.

[Beware of plagiarism: Accidental plagiarism most often occurs

when students are synthesizing sources and do not indicate where the synthesis

ends and their own comments begin or vice versa.]

4. Show the similarities or differences between the different sources in ways that make

the paper as informative as possible;

5. Represent the texts fairly–even if that seems to weaken the paper! Look upon

yourself as a synthesizing machine; you are simply repeating what the source says,

in fewer words and in your own words. But the fact that you are using your own

words does not mean that you are in anyway changing what the source says.

Conclusion

When you have finished your paper, write a conclusion reminding readers of the most significant themes you have found and the ways they connect to the overall topic. You may also want to suggest further research or comment on things that it was not possible for you to discuss in the paper. If you are writing a background synthesis, in some cases it may be appropriate for you to offer an interpretation of the material or take a position (thesis). Check this option with your instructor before you write the final draft of your paper.

Checking your own writing or that of your peers

Read a peer’s synthesis and then answer the questions below. The information provided will help the writer check that his or her paper does what he or she intended (for example, it is not necessarily wrong for a synthesis to include any of the writer’s opinions, indeed, in a thesis-driven paper this is essential; however, the reader must be able to identify which opinions originated with the writer of the paper and which came from the sources).

- What do you like best about your peer’s synthesis? (Why? How might he or she do more of it?

- Is it clear what is being synthesized? (i.e.: Did your peer list the source(s), and cite it/them correctly?)

- Is it always clear which source your peer is talking about at any given moment? (Mark any places where it is not clear

- Is the thesis of each original text clear in the synthesis? (Write out what you think each thesis is)

- If you have read the same sources,

- did you identify the same theses as your peer? (If not, how do they differ?)

- did your peer miss any key points from his or her synthesis? (If so, what are they?)

- did your peer include any of his own opinions in his or her synthesis? (If so, what are they?)

- Were there any points in the synthesis where you were lost because a transition was missing or material seems to have been omitted? (If so, where and how might it be fixed?)

- What is the organizational structure of the synthesis essay? (It might help to draw a plan/diagram)

- Does this structure work? (If not, how might your peer revise it?)

- How is each paragraph structured? (It might help to draw a plan/diagram)

- Is this method effective? (If not, how should your peer revise?)

- Was there a mechanical, grammatical, or spelling error that annoyed you as you read the paper? (If so, how could the author fix it? Did you notice this error occurring more than once?) Do not comment on every typographical or other error you see. It is a waste of time to carefully edit a paper before it is revised.

- What other advice do you have for the author of this paper?

Adapted from “Synthesis Writing,” written By Sandra Jamieson, published by Drew University, and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 1.0 License