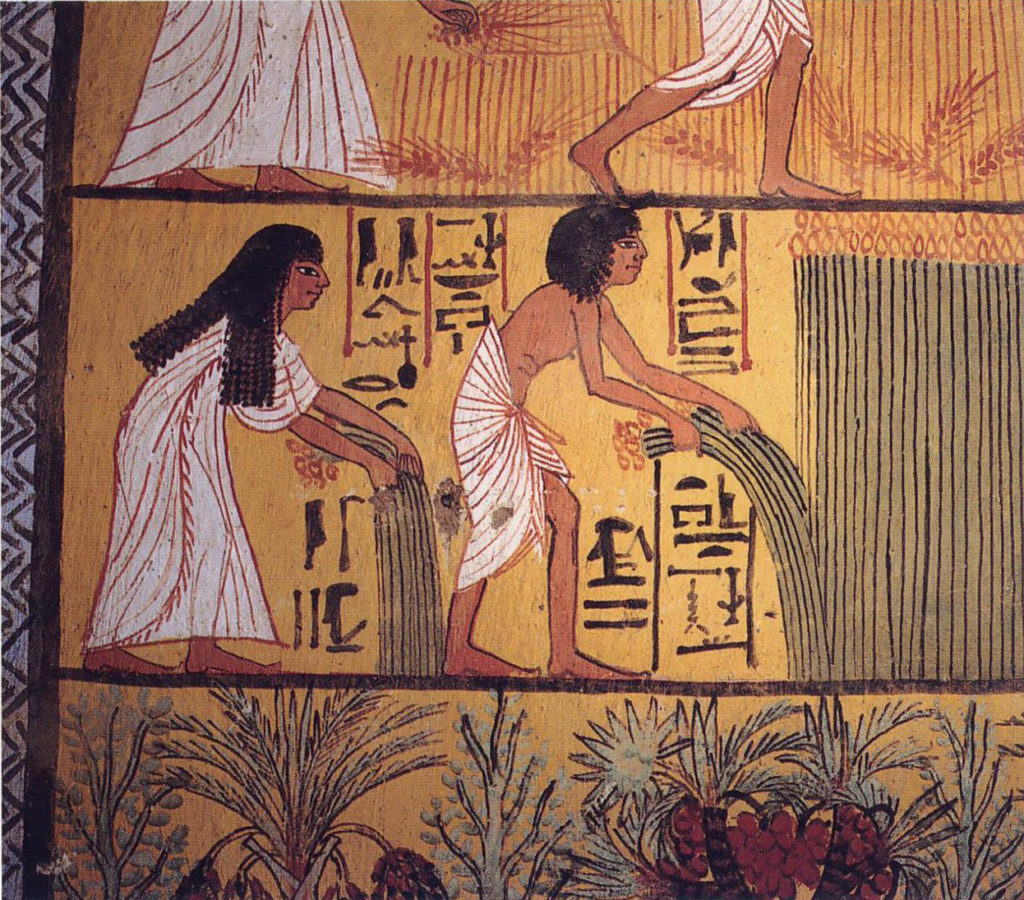

Egyptian hieroglyphic of people harvesting crops. “An early Ramesside Period mural painting from Deir el-Medina tomb depicts an Egyptian couple harvesting crops” is licensed under public domain.

‘It’s not what you find; it’s what you find out.”—attributed to archaeologist David Hurst Thomas

Domestication refers to the genetic alteration of plants or animals as a result of human control of reproduction. Agriculture refers to the reliance on domesticated plants for food. The first domestication of plants and animals developed independently in several parts of the world within a narrow window of time in the early Holocene, between 10,000 and 5,000 years ago. The Holocene refers to the geological epoch following the Pleistocene and is marked by an increasingly stable climate. Domestication of plants did not begin until after the end of the Pleistocene, suggesting that the climate stabilization that happened in the Holocene might have made the domestication of plants possible. Domestication has rightfully been seen as a major turning point in the history of the human species. One of the big questions in archaeology is: why and how does domestication occur in some areas very early on and much later or never in others?

The Idea of Diffusion

The earliest theories about the origins of domestication were strongly tied to the idea of human progress—the idea that we are constantly getting smarter and improving the human condition. These early ideas invariably emphasized discovery and invention. Since “savages”, as hunter-gatherers were referred to, did not have domestication, it must have been a difficult concept to master—kind of like prehistoric “rocket science”. Domestication was thought to be such a complicated notion that it must have been invented only once or twice by “seed geniuses” and then diffused or spread out to the rest of the world from there. Secondly, early theories of domestication tended to assume that domestication is such an obviously beneficial innovation that anyone who saw it or learned about its practice would immediately drop whatever they were doing (i.e., hunting and gathering) and start farming and herding. Basically, it was thought of as an idea waiting to happen.

This idea of cultural diffusion was taken to ridiculous extremes in the early 20th century by Grafton Elliot Smith a British anatomist-turned-anthropologist who published The Egyptians and the Origins of Civilization in 1923. Noting that, for example, the practice of embalming was found earliest in Egypt, and was now found all over the world, he decided that it had been invented there and diffused out to the rest of the civilized world. From this simple starting point, he then concluded that all the early hallmarks of civilization—agriculture, calendars, monumental architecture, metallurgy, the idea of centralized government—had been invented first by the Egyptians and diffused to the rest of the world, across the Atlantic and the Pacific, from there. William J. Perry, a British anthropologist, published several books promoting this view of civilization origins including the popular Children of the Sun (1923), in which he argued that the Polynesian practice of building monumental stone temples called heiau reflected the diffusion of the Egyptian pyramid construction to the Pacific. He also argued that European megalithic monuments like Stonehenge were a case of the same process of diffusion from Egypt.

Hyper-diffusionists thought the trappings of civilization began in Egypt and traveled the globe. The view that Egypt was the source of all civilization was strongly influenced by the finding that the Egyptians had produced the earliest known form of writing (this is almost true: The Sumerian cuneiform script is probably a little earlier). Since everybody knew that writing was the sine qua non of civilization, the idea that everything else necessary for civilized life was invented first in Egypt just logically followed. The fact that Tutankhamun’s undisturbed tomb had just been discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter and Lord Carnavon only contributed to the Egyptomania of the 1920s.

Archaeologist Glyn Daniels called this kind of “Egyptocentric” thinking hyper-diffusionism. Keep in mind that the diffusion of cultural traits does occur—there is nothing inherently wrong with the idea of diffusion as a mechanism for cultural change. But independent invention happens too. One of the most basic questions in considering any cultural innovation is whether the idea came from somewhere else, or whether it was invented or re-invented independently by chance or necessity. From what we know now, the practice of farming and herding developed independently in six or so core areas of the world, and it did so several thousand years before the development of anything we would now call “civilization”. So the focus of explanation for domestication has shifted from “how and why agriculture diffused from the centers of civilization” to “how and why domestication developed in response to local environmental and social

conditions”.

Domestication: Where and Why?

The idea that the invention of agriculture actually needed an explanation is a relatively new one. According to the Old Testament, Cain was the first human born, and he was already a metals smith

and a tiller of the earth. Domestication just came with the human package. But with the discovery of the Upper Paleolithic and the recognition of the antiquity of the earth, the question of why people began to domesticate plants and animals emerged. V. Gordon Childe, one of the great early archaeologists, suggested that as the Pleistocene ended people began to closely observe plants and animals for the first time around oases, and discovering their true nature led to their domestication. We know from studying Upper Paleolithic cave art that early humans were quite familiar with animals and cognizant of seasonal changes and migrations. Moreover, hunter-gatherers, in general, must make their living by observing wild animals and plants and figuring out the best ways to turn them into food—their lives depend on it. While Childe was right about the timing of domestication, he was probably wrong that hunter-gatherers just didn’t have a clue about plant and animal reproduction.

Investigating the beginnings of agriculture in the mid-1900s, American archaeologist Robert Braidwood showed that plant domestication in the Near East began in the hilly flanks of the Fertile Crescent, the natural habitat of the wild progenitors of the first domesticated plants. These grasses were so abundant that experimental archaeology showed that hunter-gatherers could easily live off of them without even domesticating them. This period where wild grains were harvested before domestication is called the Natufian. This point that grains could have been harvested by hunter-gatherers was brought home by a simple experiment carried out in the summer of 1967 by a member of Braidwood’s archaeological team at the site of Çayonü in Turkey. Jack Harlan was an American crop scientist who had been hired by Braidwood to consult on the growth of wild cereals. Çayonü is an early Neolithic site located in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains in the prime habitat of a wild form of wheat called einkorn (You can still einkorn cookies in some stores. They are delicious).

Harlan noticed that dense stands of wild einkorn covered the hillsides of rich volcanic soil around the site, as they had back in the early Neolithic when the site was occupied. Acting on a hunch, Harlan reconstructed a Neolithic-style hand sickle using a wooden handle with microlith blades embedded in it, using archaeologically recovered examples for models. Using the hand sickle and some locally made baskets, Harlan was able to harvest up to 2 pounds of wild cereal grain per hour from the wild stands around the site. Furthermore, since the site was located on a hillside, Harlan found he could move up the hill and harvest more newly ripened grain as the summer season progressed to higher elevations. From these results, Harlan estimated that a family of four could harvest enough wild einkorn to feed themselves for a year in the space of only three weeks, by moving up the hillside. Once again, experiment archaeology showed what was possible, but raised further questions. Jack Harlan’s wheat harvest raised the question: Why bother to

become a farmer when you can live as a hunter-gatherer off the land and let the wild plants sow themselves?

Neolithic sickle with microliths embedded. By Wolfgang Sauber (Own work). [GFDL

(http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via

Wikimedia Commons

What’s the advantage of domestication?

It is commonly thought that agriculture gives people more free time—that it is some kind of labor-saving device. It isn’t. Ethnographic research (research on modern-day people) has shown that agriculturalists generally spend more hours of work per week in subsistence activities than hunter-gatherers do. Agriculture requires clearing land, weeding, creating technology to harvest crops, hours of processing (grinding) seeds, and cooking not to mention the labor involved in making and maintaining permanent structures. This is why many archaeologists maintain that to explain why people began to domesticate animals and plants, it is first necessary to explain why people found it necessary to work harder to survive and reproduce, assuming that people will only work as hard as they have to do so. Domestication allows people to live off a smaller unit of land by putting more effort into food production. From this perspective, you can see that domestication could be a reasonable choice in the face of population growth and resource depletion, where one might have to get by on a smaller unit of land. The only option would be to intensify effort to get more out of less. In turn, sedentary life appears to promote increased population, or at least population densities. Rather than seeing domestication as a serendipitous discovery that freed humanity from the risks and privations of life as a hunter-gatherer “savage”, domestication and subsistence intensification have come to be a grim necessity. In the long scheme of things, the history of “improvements” in subsistence practices is the history of declining individual work efficiency.

The Evidence for Domestication

During the Mesolithic, changes in diet with domestication brought about changes in settlement and technology. The archaeological tool tradition or suite of tools, associated with the domestication of plants and animals is called the Neolithic, or New Stone Age. Houses (domestic structures) required increased labor to construct as villages became increasingly permanent. There was an even greater emphasis on grinding stones with an increased need to process grains. Some grinding stones at the site of Abu Hureyra in Syria were gigantic, attesting to the amount of cereal processing going on at the site. Because agriculture is a seasonal activity, grains had to be stored for future consumption. During the Neolithic, pottery, grain bins, and storage pits become common. Because domestication involves the genetic alteration of plants by selective breeding, the morphology of seeds changed during the Neolithic. For starters, they become bigger as people favor plants that produce larger seeds. Secondly, they develop a stronger rachis, the part of the plant that holds the seed onto the plant. A stronger rachis prevents the seed from doing what it does naturally to reproduce—blow away in the wind. If you look at an ear of corn, you can easily see what we’ve done to this plant. The rachis is so strong, that it can no longer reproduce without the assistance of people. The same is true of wheat. Second, the glume or seed coat of domesticated grains is weaker. The weaker seed coat is good for humans because it makes the seed softer and therefore easier to process and digest.

Some of the earliest evidence for domesticated plants comes from the flanks of the Fertile Crescent on the margins of the Taurus and Zagros Mountains in the Near East in Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey. The site of Abu Hureyra in Syria, excavated in 1974 by A.M.T. Moore, is a tell, or an accumulated mound created by the continuous occupation. The site now lies beneath the Lake Assad reservoir near the Syrian border with Turkey. The site dates to the late Mesolithic/early Neolithic, around 8,000–13,500 B.P. About 11,000 B.P. the village’s inhabitants started growing cereal grains, rye being the first known domesticated grain. During the later occupation at Abu Hureyra, architecture consisted of mud-brick structures covered by mud plaster. Houses had plaster floors and were equipped with storerooms for keeping food and hearths for cooking.

Excavations at Abu Hureyra showed the expected change in morphology for seeds from wild to domesticated:

“What we expected to find from the hunter-gatherer levels at the site was lots of wild cereals. These are characteristically very skinny and we found plenty of them. But then, at higher and later levels, we found things that did not belong there. There were these whacking, great fat seeds, characteristic of cultivation. “(Gordon Hillman, University College, London, on Abu Hureyra excavations).

Another fascinating discovery for the Neolithic occupation of Abu Hureyra is that osteologist Theya Molleson could determine who was doing the laborious grinding of seeds based on skeletal abnormalities. She discovered a window into the sexual division of labor, and how people organized tasks by sex. A final tell-tale sign of domestication, especially in the New World, is dental caries, or cavities. During the Archaic period (the Mesolithic of the New World), the incidence of cavities is low. Later in the New World when populations become supported largely by maize, which contains sugars, the incidence of cavities skyrockets. The domestication of wheat, rye, and barley spread out from the flanks of the Fertile Crescent to Cyprus, Crete, mainland Greece, and Europe. Domesticated animals also came with these domesticated plants. The conversion from hunting and gathering to farming in Europe did not all happen at the same time, and some populations remained foragers for longer periods than others. A major debate in archaeology is whether people migrated to these areas with their domesticated, or whether the domesticates diffused “down the line” as well as the route into Europe that migrants took. The genetic markers (male Y chromosome and SNPS) for southeast Europe and Greece indicate ties to the Near East, while in Germany, France, and northeastern Spain there is less evidence of eastern migrants. The study of ancient DNA, which is rapidly becoming more feasible, will hopefully further clarify how domesticates spread. It is clear though that migrations of people into Europe from the Near East is not just a modern phenomenon. So while Kennewick Man is connected to Native Americans, it is less clear how modern Europeans are related to people of the Upper Paleolithic.

Agriculture began along the flanks or hill slopes of the Fertile Crescent. By Nafsadh (Map of fertile cresent.png) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Following the introduction of plant and animal domesticates to Europe, several different archaeological cultures sprang up. In western Europe, people began to build large stone monuments like menhirs, and large standing stones, in the 5th millennium B.C. (4000’s B.C) along with earthen mounds called “long mounds”. In the Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Kosovo, Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Romania), enormous villages, and even tells, formed. Copper and gold mining and the production of sumptuary goods can be found at the Bulgarian Neolithic site of Varna along the Black Sea. One male burial, 40-50 years old, contained gold beads, rings, bracelets, hair, and body ornaments (including a golden penis sheath). He also had copper axes and a stone ax scepter. Some scholars think that with the spread of domesticates to Europe came the Indo-European languages common in Europe today, including Germanic, Slavic, Italic, and Celtic languages (other Indo-European languages include Farsi, Urdu, Hindi, and Kurdish). Thus, the English in which this text is written may have had its roots in the spread of agriculture from the Near East. This debate continues to puzzle both linguists and archaeologists alike.

Domestication also began independently in China with millet and rice at around 9,000 BP. Settlements and pottery begin to become prevalent (though there is evidence for even earlier pottery in China). At the site of Banpo (ca. 6,000 BP) near Xi’an in China, houses are circular and excavated deeply into the earth. Pits were excavated into the structures for the storage of food. The Neolithic of China also contains evidence for the world’s earliest alcohol dating to around 9,000 years ago. Patrick McGovern is a biomolecular archaeologist who specializes in ancient alcohol made from rice, fruits, and other ingredients. McGovern uses techniques like infrared spectrometry to analyze residues on pottery fragments to determine the ingredients of ancient alcohol. This technique bombards a sample with infrared light, and the absorption of the light reveals what kinds of bonds are present in the sample. Each organic compound will respond differently and can potentially be identified.

Domestication in the New World

The first New World domesticate was squash, ca. 8,000-10,000 B.P. in southern Mexico and South America. Domestication is marked by increased seed length, increased peduncle (stem) diameter, and changes in overall shape compared to wild species. While there were other domesticates, the big story of domestication in the New World revolves around maize. Among modern Pueblos, for example, corn is life, corn is mother. While the Old World has several cereal crops, maize was the New World’s one major native grain. Other native grains, such as chenopodium and quinoa, were also domesticated, but are not as productive as maize. Guilá Naquitz, in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico, is the site of the earliest evidence of maize cobs dating to ca. 6,200 B.P. Other evidence on grinding stones from Xihuatoxtla Shelter in Mexico indicates an early form of maize around 8700 BP. These remains called phytoliths a kind of “plant fossil” made from silicon dioxide (SiO2) provided direct evidence for maize. Plants take up SiO2, which gets incorporated into their cell structures. Phytoliths are used extensively in archaeology to infer diet. (Phytoliths can be found in dental calculus as a direct index of what an individual ate). Most biologists agree that teosinte, a wild grass that grows in the vicinity of Guilá Naquitz today in the Balsas River Valley, is the wild ancestor of maize. To begin, maize was tiny, and artificial selection (traits selected by people, not nature) produced slow increases in maize productivity over time. Only around 4,000 B.P. was maize large enough to support village life.

Maize spread from southern Mexico northward into what is today the U.S. and southward into South America. So, maize ultimately comes from Mesoamerica, from central Mexico through Central America, an area we will discuss later in this book. This is a legitimate case of diffusion. It arrived first in the American Southwest ca. 3,000 B.P. reaching the eastern woodlands of the U.S. by around AD 1-200. Like the flanks of the Fertile Crescent, the Valley of Oaxaca was the source of a major domesticate that spread far and wide. Ultimately, maize became the basis for major civilizations throughout the Americas: Olmec, Maya, Aztec, Moché, Inca, Ancestral Pueblo, and Mississippian, which we will discuss in more detail in future chapters.

Ground stone

As we saw in the Mesolithic and Archaic, archaeologists use the term ground stone to refer to stones used in the processing of grains. In the Old World, the grinding slabs are called querns rather than metates. These slabs and stones become increasingly larger and more elaborate with the emergence of the domestication of cereals (the grains of grasses). The making of ground stone is labor-intensive and the grinding of cereals could take hours each day. Processing like this increases the number of calories that are available to humans to eat, which helps explain why someone might spend hours a day processing grains. Early in the domestication process, people were likely parching grains or even making popcorn rather than spending time making flour. In many cases around the world, there is evidence that women were largely responsible for this task, especially as the importance of domesticates in the diet increased.

Animal Domestication

Like plants, animals undergo morphological changes with domestication as well. We have already discussed some of the changes from wolf to dog. In addition to morphological changes, the population structure of animals can change. Female animals may be kept for breeding purposes, while males might have been used for labor or food. Male cattle or oxen might show wear and tear on their skeletons from the plow. By identifying male and female animals and their ages from the skeletal record, along with wear skeletal abnormalities, archaeologists can see how animals were used. Of course, not every animal is conducive to domestication, which explains why some animals were originally domesticated and continue to be used as food today. The following outlines the factors influencing animal domestication:

- The animal’s diet should not compete with the human diet.

- The animals’ growth rate should be rapid (e.g., great apes have slow growth).

- The animal should not be too aggressive (e.g., bears, hippos, rhinos, African buffalo).

- The animal should not tend to panic (e.g., deer, antelope).

- The animal should live in permanent herds and have a well-developed dominance structure. Humans can then assume the top position in the hierarchy.

Cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep have qualities that make them amenable to domestication by humans. Grazing animals like cattle are especially productive domesticated animals because they digest cellulose and convert it to energy and protein “on the hoof”. They can also eat the stalks and leaves of grasses, while humans harvest and use the seeds.

Today, domesticated animals have now reached epic proportions with around 1 billion cattle in the world. Beef production is a billion-dollar industry. Animal husbandry is not what it used to be in the Neolithic; they are now raised on a massive scale. Cattle take up a huge amount of land to raise along with a huge amount of water. In the U.S. they eat mostly soy and corn, which they are not built to eat, causing additional problems like the production of methane and the use of antibiotics. While wild (non-domesticated) animals grace the pages of children’s books, in the real world wild animals pale in comparison to the number of domesticated animals. Domestication has changed not only how humans eat and live, but affected all the earth’s animals. F. Dalton prophesied in 1865 in “The First Steps Towards the Domestication of Animals”:

It would appear that every wild animal has had its chance of being domesticated, that those few which fulfilled the above conditions were domesticated long ago, but that the large remainder, who fail sometimes in only one particular, are destined to perpetual wildness. As civilization extends they are doomed to be gradually destroyed off the face of the earth as useless consumers of cultivated produce.

Consequences of Domestication

We know one consequence of agriculture is the ability to live off a smaller area of land by increasing the energy put into production. Agriculture can support more people per unit of land, and so population size or density tends to increase. This has consequences. First, trash builds up and attracts vermin and bacteria, which are vectors for disease, and can also pollute water sources. Secondly, domesticating animals brings animal tissues and feces in contact with humans spreading zoonotic, or animal-born, diseases. Examples of zoonotic diseases include chickenpox, hantavirus, mad cow disease, swine flu, yellow fever, ebola, hantavirus, and many, many more. Another consequence of agriculture is that people become very concerned about land rights because even very small areas of land are a family’s lifeline.

People become sedentary, investing more in houses and storage units. At Catalhoyuk in Turkey, people live near a source of plaster and become what Ian Hodder calls “plaster freaks”, constantly refurbishing and remodeling their houses. As populations increase, there are few other options but to defend one’s land rights or migrate to a completely new area. As people become more sedentary and reliant on one area of land, they begin formulating ways of justifying land rights, often through the establishment of ancestral ties to an area. At Abu Hureyra and other Neolithic sites in the Near East, the interesting phenomena of plastered skulls occur. These are actual skulls that were covered in plaster to resemble a face, not so different from a forensic reconstruction. A combination of realistic and caricature-like modeling of facial features on the skulls suggests individual identities remained with the skulls of the deceased. The skulls may have been modeled and decorated in a manner that captured the essence of a personal trait or quality that reminded the living of the deceased. After burial or excarnation (removal of flesh), skulls were retrieved and used in other contexts. These plastered skulls have been found buried separately from bodies and sometimes they occur in “caches.” The murals of vultures and heads at Catalhoyuk in Turkey may represent the defleshing process, following which the skull could be retrieved for use. The plastered skulls appear to represent a form of ancestor veneration a common phenomenon in agricultural societies. Modern people sometimes retain portions of dead individuals to retain an association with that individual, especially if he or she held power. Retaining the skulls of powerful ancestors may have legitimized and reinforced claims to land and other resources, particularly as populations grew and land became scarcer. In a way, this practice of displaying important social figures after death is not so removed from modern life. Vladimir Lenin’s body is on display in a mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square. The mausoleum incorporates elements of ancient burial monuments such as the Temple of Inscriptions in Honduras (see Chapter ** The Classic Maya) and the Egyptian Step Pyramid (see chapter ** Dynastic Egypt). The preserved remains of Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), for example, are on display at the University College in London at his own request. He has even “attended” council meetings where he is listed as “present,” but not voting. Bentham serves as a kind of totemic ancestor for the university.

Neolithic skulls may have been on display or buried in homes. “The three plastered skulls in situ at Yiftahel” by Viviane Slon, Rachel Sarig, Israel Hershkovitz, Hamoudi Khalaily, Ianir Milevskiis licensed under CC BY 2.5