Part 1: Chapter 1.1

Communication courses will teach students that communication involves two parties—the sender and the receiver of the communicated message. Sometimes, there is more than one sender and often, there is more than one receiver of the message. The main purpose of communication whether it be email, text, tweet, blog, discussion, presentation, written assignment, or speech is always to help the receiver(s) of the message understand the idea that the sender of the message is trying to get across. This section will focus on electronic communication in a college course.

Email or message

An email or message sent to your instructor is often the result of a question you may have. Many students think sending a message or email to their instructor shows that they are stupid or that they are the only ones not understanding something, so they keep quiet and go on trying to do work that they really do not understand. Other students think that their teacher is their own private tutor, so they email or message the teacher several times a day to ask questions that likely have answers in the syllabus and in the learning module instructions. Both of these behaviors are unhelpful and frustrating to the students and the instructor.

It is a good idea to balance these two opposite behaviors. Ask a question if you are unable to find the answer yourself. Your instructor likes hearing from her students and will have a general response time to emails and messages noted in the syllabus. Give your instructor some time to respond to your email and be sure to check your inbox for her reply.

On the other hand, avoid monopolizing your teacher’s email inbox with dozens of emails and messages per week and expecting the teacher to respond immediately. Nobody enjoys having the inbox blown up with multiple messages by the same person. Try to remember your instructor will likely have many other emails from administrators, staff, and of course other students.

Avoid sending emails and messages because when you are panicked, frustrated, or angry. Walk away from your computer and return at a later time when you feel calmer. Then re-read the instructions, or syllabus, or the course materials you find confusing, and if you still cannot find the answer because it is not there, definitely email or message your instructor.

So now that you have decided to email or message your instructor, decide if your instructor prefers a certain type of communication. Some instructors prefer emails from the college-wide email system while others prefer messages that go out from the online course shell itself. Some instructors may prefer phone calls and some may prefer texts.

Netiquette

Keep your message brief, specific, professional, and grammatically correct. Include a greeting such as “Dear Professor Alvarez”, specific details about your question, for example the name and number of the assignment, and a close, such as “Best regards” followed by your name. Include a subject line for your email or message that is not your name or “Hello” but a short description of your question. Some instructors even give you instructions as to how they want emails or messages formatted. For more information about how to write an email or message to your instructor, watch this video from Learning to Learn by Kwantlen Polytechnic Institute.

It is never wrong to be formal and professional with your college instructor who is trying to prepare you for a work environment where professional and formal messages and emails need to be written and sent. Remember that your instructor is not your friend and that an email or message is not a text message. The opposite of this rule, however, is wrong, which is that it is ok to send an informal or colloquial message and to assume your instructor is your friend or acquaintance and that an email or message is the same as text message.

Communication on Public Discussion Boards

Whenever you are being asked to communicate or post in a discussion forum or other communication mode, you need to ask yourself if there will be one recipient or several. In other words, who will be your readers? Is the forum private so that only your instructor or only a group of classmates or only a specific classmate can see it or is it public so that everyone, all of your classmates and your instructor can see your post? Check the forum to which you are posting for these settings.

Create a post according to the recipient(s). It is nice to address a classmate by name if you are responding to a specific person in a discussion forum. Online classes can be a solitary experience, so it can be nice when a classmate is actually responding to you, talking to you, personally. It is also advisable to use a greeting such as “Classmates” if you are addressing a discussion post to everyone in the class. Most of the time, discussions tend to be public, so you can make sure of the assignment’s settings before you post.

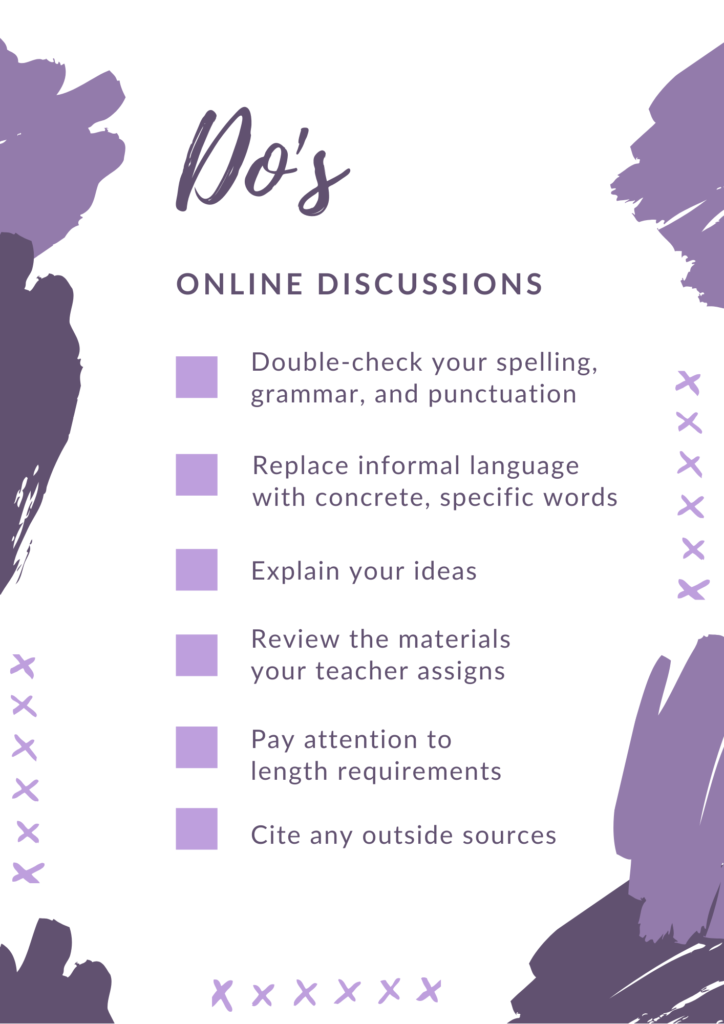

Do’s: Discussions usually have specific guidelines for posts. Most require you to use college English and write in complete sentences. This chapter from CNM’s grammar OER covers appropriate language. Avoid text language, capitalize “I”, and check your spelling, grammar, and punctuation before submitting your posts. Sometimes there is a certain number of sentences required. Avoid short posts, such as “I agree” because it is too general and not specific enough. Explain what you agree with and why. Then there may be questions that your instructor is asking that need to be answered, so make sure you answer your instructor’s questions. Often, there is a reading that needs to be completed before you post. Make sure you read the required text before posting instead of just “winging it” because your classmates and teacher can tell.

Don’ts: Avoid copying and pasting your own post to respond to several of your classmates so that they all receive the same post from you. Your instructor who will be viewing and grading your posts can tell that your posts are identical and is unlikely to give you full credit for identical posts. Second, avoid copying and pasting your classmates’ posts to present as your own. There is a timestamp on your posts in an online classroom, and your instructor will have physical evidence of who posted a response first. Also, your classmates and instructor will notice your copied post, and you will be guilty of plagiarism. The discussion board is a public forum. Last, do not post unrelated ideas; for example, if you are asked about the main idea of a text you read, make sure to read the text, and respond by giving what you think is the main idea, not by posting that you liked the text because of a personal experience you had. It isn’t wrong to include personal things such as that you liked the text, but be sure to answer the instructor’s questions first to earn full credit.

Peer Reviews

Peer reviews can be tricky to navigate. When students are asked to provide peer feedback to each other, it is an activity intended to improve everyone’s writing, not an opportunity to give each other unwarranted compliments or bash each other. Peer feedback activities have an educational purpose which is putting the writer into the position of the reader and with this switch, reflecting on and improving one’s own writing. Read more about the peer review process in Chapter 10 of this OER.

Giving Feedback

When giving feedback, try to answer your instructor’s questions, but of course, you should carefully read your classmates’ writing first. For example, if you are supposed to identify the main idea of your classmate’s writing, be sure to look for the main idea. If you can’t find it, say, “I looked but couldn’t find it”, instead of “You didn’t include one.” Both may mean the same thing, but the former sounds less aggressive and accusatory, and the reason for that is that you state that you as the reader tried to accomplish the given task of finding the thesis statement.

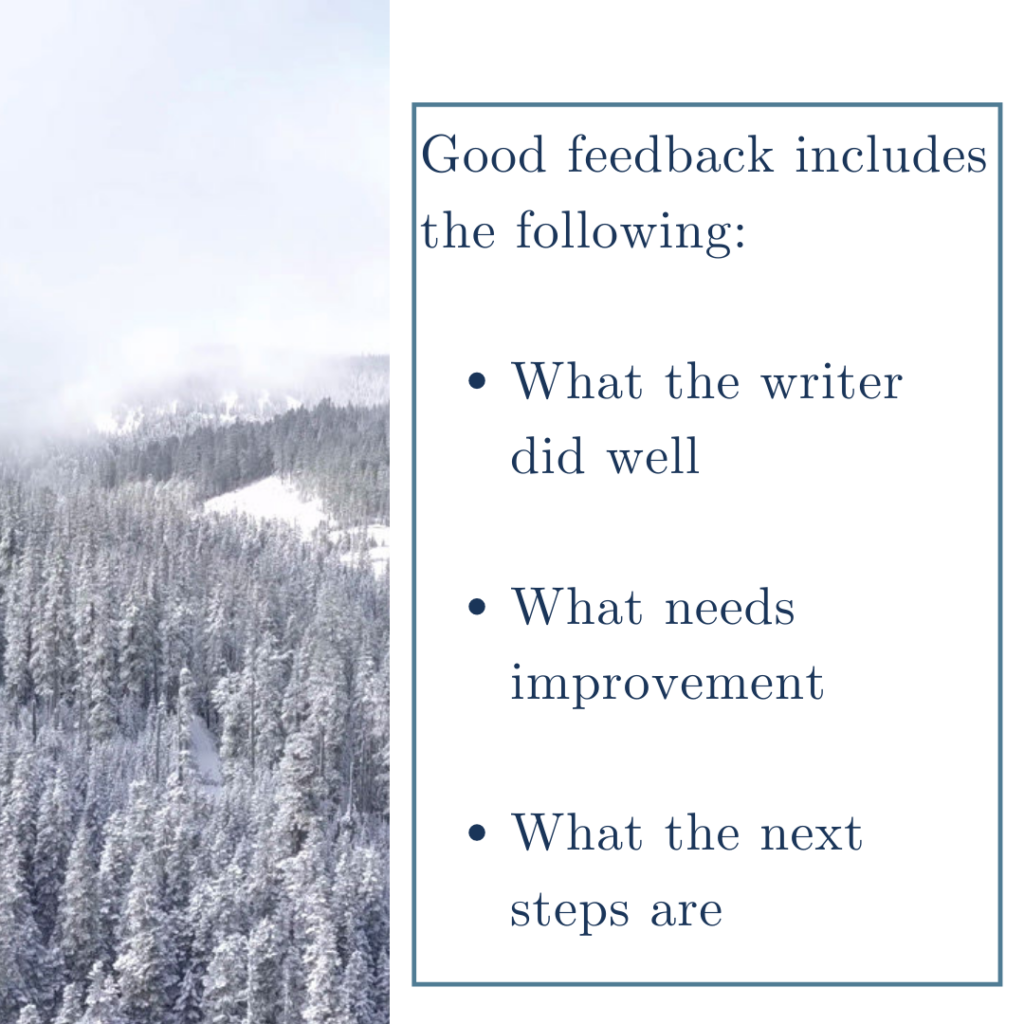

Good peer reviews should begin with something that the writer did well, but they should be honest in stating what needs improvement.

According to Alice Macpherson and Christina Page (Learning to Learn), good feedback should include the following:

- What the writer did well

- What needs improvement

- What the next steps are

Receiving Peer Feedback

When receiving peer feedback, remember that your classmates are being asked to perform a task and that they, just like you, are just trying to perform the task the teacher asked them to perform. With repeated practice you and your classmates will get better and better at giving each other peer review. Some of your classmates will give you great feedback and others might not have actually read your paper so their feedback might not be useful to you.

Avoid the “Ugly Baby Syndrome” that some writing teachers talk about. Someone who gives you constructive criticism on your writing may come across as someone who is calling your baby ugly. Perhaps your baby just needs a haircut. Or maybe your baby needs a diaper change. Your baby is still your creation, and you have opportunities to make your ideas shine. Fortunately, you can improve your writing, which takes us to the next point. Should you change your writing?

If two or several of your classmates make the same comment about your writing, the likely answer to that question is yes. If your teacher or a tutor has in the past commented on the same point, again the answer is yes. If the feedback is specific to the questions that your instructor asked, the answer is also yes.

If, however, your classmate’s feedback is off the topic and commenting on points not included in the peer review questions, I suggest you take a step back and return to your paper with an objective view to see if you indeed need to take action on your classmate’s feedback. And if your peer gives you feedback on grammar, and you are not certain the feedback is correct, ask for a second opinion.

Lastly, thanking your classmates for feedback is a gracious way to acknowledge that your classmates attempted to complete the assignment and took the time and care to read and comment on your writing.

This chapter is a synthesis of two texts:

- Some sections of this chapter written by Angelika Schwamberger, published by Central New Mexico Community College, and licensed using Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Some sections adapted from Learning to Learn Online by Alice Macpherson and Christina Page, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.