Part 6: Chapter 31

The textbook Successful Writing introduces strategies that will help you locate good information for any college-level paper. While you were choosing a paper topic and determining your research questions, you conducted preliminary research to stimulate your thinking. Your research proposal included some general ideas for how to go about your research—for instance, interviewing an expert in the field or analyzing the content of popular magazines. You may even have identified a few potential sources. Now it is time to conduct a more focused, systematic search for informative primary sources and secondary sources.

Using Primary Secondary Sources

Writers classify research resources in two categories: primary sources and secondary sources. Primary sources are direct, firsthand sources of information or data. For example, if you were writing a paper about the First Amendment right to freedom of speech, the text of the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights would be a primary source.

Other primary sources include the following:

-

Research Articles

-

Literary Texts

-

Historical documents such as diaries or letters

-

Autobiographies or other personal accounts

Secondary sources discuss, interpret, analyze, consolidate, or otherwise rework information from primary sources. In researching a paper about the First Amendment, you might read articles about legal cases that involved First Amendment rights, or editorials expressing commentary on the First Amendment. These sources would be considered secondary sources because they are one step removed from the primary source of information.

The following are examples of secondary sources:

-

Magazine articles

-

Biographical books

-

Literary and scientific reviews

-

Television documentaries

Your topic and purpose determine whether you must cite both primary and secondary sources in your paper. Ask yourself which sources are most likely to provide answers your research questions. If you are writing a research paper about reality television shows, you will need to use some reality shows as a primary source, but secondary sources, such as a reviewer’s critique, are also important. If you are writing about the health effects of nicotine, you will probably want to read the published results of scientific studies, but secondary sources, such as magazine or journal articles discussing the outcome of a recent study, may also be helpful.

Once you have thought about what kinds of sources are most likely to help you answer your research questions, you may begin your search for print and electronic resources. The challenge here is to conduct your search efficiently, so writers use strategies to help them find the sources that are most relevant and reliable while steering clear of sources that will not be useful.

Finding Print Resources

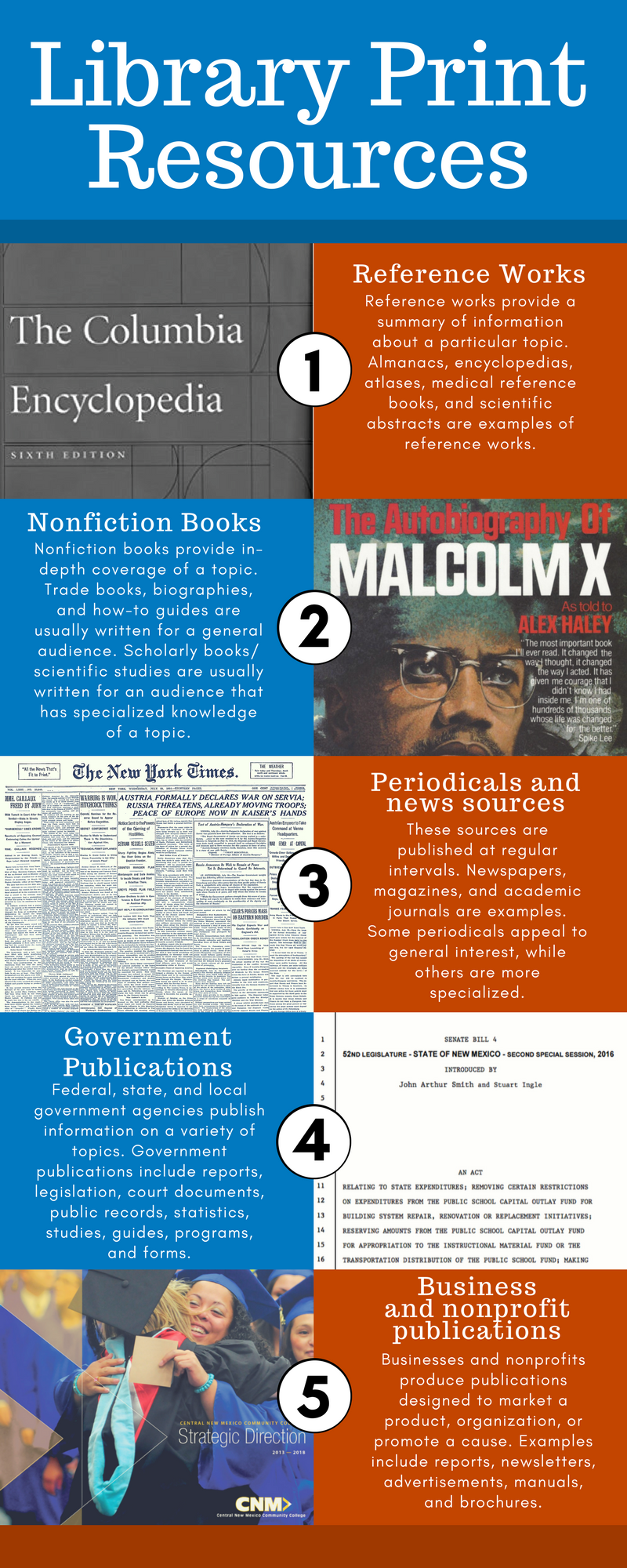

Print resources include a vast array of documents and publications. Regardless of your topic, you will consult some print resources as part of your research. (You will use electronic sources as well, but it is not wise to limit yourself to electronic sources only, because some potentially useful sources may be available only in print form.) Table 31.1 lists different types of print resources available at public and university libraries.

Table 31.1 Library Print Resources

Some of these resources are also widely available in electronic format. In addition to the resources noted in the table, library holdings may include primary texts such as historical documents, letters, and diaries.

When going about your research, you will likely use a variety of sources—anything from books and periodicals to video presentations and in-person interviews.

Your sources will include both primary sources and secondary sources. As you conduct research, you will want to take detailed, careful notes about your discoveries. These notes will help trigger your memory about each article’s key ideas and your initial response to the information when you return to your sources during the writing process. As you read each source, take a minute to evaluate the reliability of each source you find.

Using Periodicals, Indexes, and Databases

Library catalogs can help you locate book-length sources, as well as some types of nonprint holdings, such as CDs, DVDs, and audio books. To locate shorter sources, such as magazine and journal articles, you will need to use a periodical index or an online periodical database.

These tools index the articles that appear in newspapers, magazines, and journals. Like catalogs, they provide publication information about an article and often allow users to access a summary or even the full text of the article.

Print indexes may be available in the periodicals section of your library. Increasingly, libraries use online databases that users can access through the library website. A single library may provide access to multiple periodical databases. These can range from general news databases to specialized databases. Table 31.2 describes commonly used indexes and databases.

| Resources | Format | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| eLibrary Academic (ProQuest) | Online | Database that archives content from newspapers, magazines, and dissertations |

| Psychology Collection (Gale) | Online | Database that archives content from journals in psychology and psychiatry |

| Business and Company ASAP (Gale) and Business Insights Essentials | Online | Database that archives business-related content from magazines and journals |

| CINAHL Complete, Health Reference Center Academic | Online | Databases that archive articles in medicine and health |

| EBSCOhost | Online | General database that provides access to articles on a wide variety of topics |

Reading Popular and Scholarly Periodicals

When you search for periodicals, be sure to distinguish among different types. Mass-market publications, such as newspapers and popular magazines, differ from scholarly publications in their accessibility, audience, and purpose. Consult your instructor because they will often specify what resources you are required to use.

Newspapers and magazines are written for a broader audience than scholarly journals. Their content is usually quite accessible and easy to read. Trade journals that target readers within a particular industry may presume the reader has background knowledge, but these publications are still reader-friendly for a broader audience. Their purpose is to inform and, often, to entertain or persuade readers as well.

Scholarly or academic journals are written for a much smaller and more expert audience. The creators of these publications assume that most of their readers are already familiar with the main topic of the journal, and the use of jargon is acceptable. The target audience is also highly educated. Informing is the primary purpose of a scholarly journal. While a journal article may advance an agenda or advocate a position, the content will still be presented in an objective style and formal tone. Entertaining readers with breezy comments and splashy graphics is not a priority.

Because of these differences, scholarly journals are more challenging to read. That doesn’t mean you should avoid them. On the contrary, they can provide in-depth information unavailable elsewhere. Because knowledgeable experts carefully review the content before publication, scholarly journals are far more reliable than much of the information available in popular media. Seek out academic journals along with other resources. Just be prepared to spend a little more time processing the information.

Consulting a Reference Librarian

Sifting through library stacks and database search results to find the information you need can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack. If you are not sure how you should begin your search, or if it is yielding too many or too few results, you are not alone. Many students find this process challenging, although it does get easier with experience. One way to learn better search strategies is to consult a reference librarian.

Reference librarians are intimately familiar with the systems libraries use to organize and classify information and are skilled at assisting searchers find just what they are looking for, and helping you improve your research skills at the same time. The library home page can be found below.

Research Librarians at CNM can be found on six campuses. Table 31.3 “CNM Library Contact Information lists contact information for each branch.

| Campus | Contact |

|---|---|

| Main Campus | (505) 224-3274 |

| Westside Campus | (505) 224-4953 |

| South Valley Campus | (505) 224-5016 |

| Montoya Campus | (505) 224-5721 |

| ATC Learning Commons | (505) 224-5152 |

| Rio Rancho Campus | (505) 224-4953 |

CNM’s librarians can help you locate a particular book in the library stacks, steer you toward useful reference works, provide tips on how to search databases and electronic research tools, or help you break down a complex research question. Take the time to see what resources you can find on your own, but if you encounter difficulties or just want to learn more, ask a librarian. CNM’s librarians can be accessed via an online chat function under “Get Help” on the library homepage or you can email reference librarians at [email protected].

There is also a research guide through the CNM library that is intended for English students specifically: English Subject Guide