The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 14: World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II

- Manhattan Project

- Site Y

- Testing the Bomb

- Impact on Local Communities

- References & Further Reading

The Manhattan Project brought New Mexico into the center of national and international debates about nuclear weaponry and technology. Many historians and other analysts have written about the development of the program at Los Alamos, but as geographer Jake Kosek has pointed out, “LANL [Los Alamos National Laboratories], as an institution that has so fundamentally changed the world, is rarely situated in context” of the surrounding region and its peoples.27

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

When considered in the context of the local people who helped to construct the facility, who continue as members of its staff, and whose lands and resources were both taken away and contaminated by LANL, the colonial nature of the relationship between the laboratory and neighboring Rio Arriba County is brought into sharp relief. As one nuevomexicana put it, Los Alamos is “the white sheep of the family.”28 Its population was enumerated the 2000 U.S. Census as ninety-four percent white, and Los Alamos County is numbered as the fourth-wealthiest in the nation. By contrast, the four neighboring counties are between seventy and ninety-five percent non-white.

By some accounts, the areas surrounding Los Alamos are designated using the term “minority” instead of identifiers like “non-white,” “nuevomexicano,” or “Native American.” That the majority of a locale’s population can be deemed a “minority” speaks to the colonial nature of relations between LANL—by—extension the federal government, and northern New Mexican communities.29

About fifteen percent of Rio Arriba County adults have bachelor’s degrees or higher, compared to Los Alamos which boasts the highest number of Ph.D.s per capita in the nation. Additionally, the dropout rate in Rio Arriba is about twelve percent; in Los Alamos County nearly ninety percent of students not only graduate high school, but then go on to attend a four-year college or university. Los Alamos could not appear any more different than the rural region of northern New Mexico of which it forms a part.

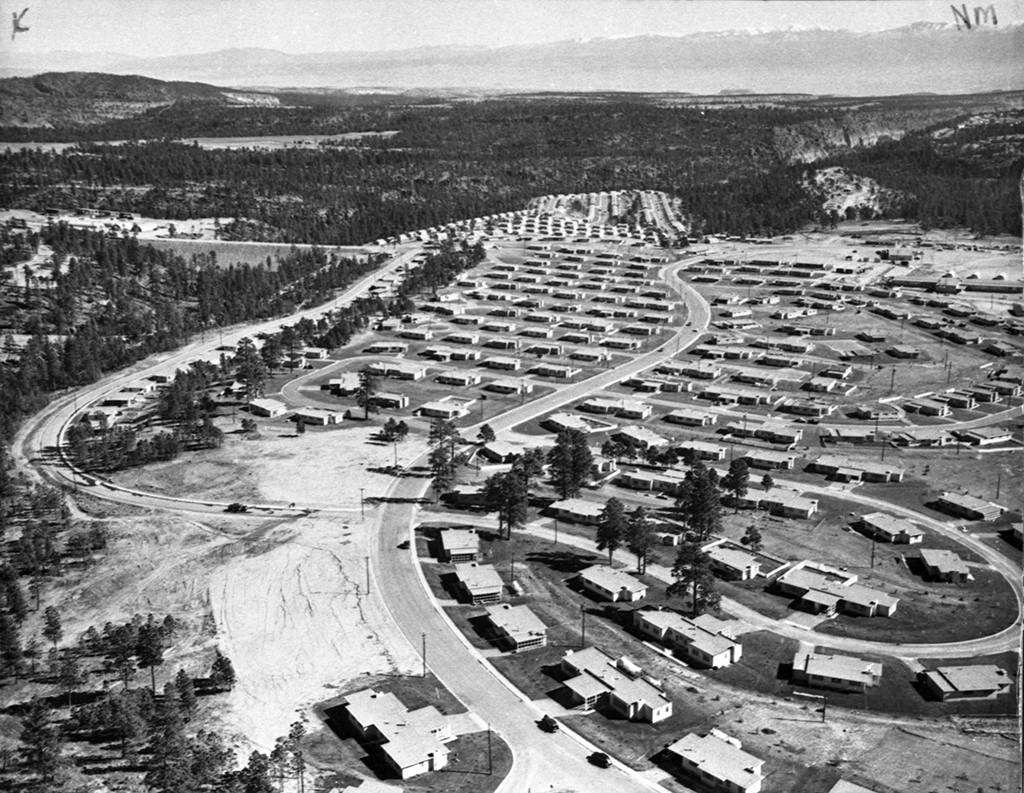

Yet the histories of Los Alamos and northern New Mexico are intimately interconnected. Kosek refers to “these often-opposed places” as “co-constituted colonial geographies.”30 LANL and its contractors supply surrounding towns with economic survival. Such was the case since the construction of Site Y in 1943. The northern New Mexican Sundt and Morgan and Sons construction companies secured the contracts to build the laboratory facilities and housing districts to serve the Manhattan Project. Most of the laborers were nuevomexicanos and Pueblos.

Courtesy of U.S. Department of Energy

Local people were employed at Site Y after the initial construction as well. They worked as maids, janitors, and technicians to maintain the facilities themselves. As a community took shape around the labs, those able to secure high-paying positions were those who held advanced degrees in physics and engineering. In the early 1940s, that distinction “excluded the working class and virtually all non-Anglos.”31 Indeed, a person’s place of residence directly corresponded with his or her job at Los Alamos.

Nuevomexicanos and Pueblos thus contributed to the construction of Los Alamos alongside Anglo American scientists and their families. Some locals, such as Popovi Da—a well-known San Ildefonso pottery artist, assisted physicists in the labs. Most, however, worked in service jobs to support the existence of Site Y. Pueblo maids from the surrounding towns of Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, and Pojoaque performed household chores to free up time for Anglo women to work at the Tech Area. They also helped new mothers care for their babies.

Bob Crooks (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 055375.

For many Los Alamos residents, the interaction with the maids was their first experience with Native American people. Wife and mother Bernice Brode marveled at the maids who “dressed in Pueblo fashion, short, loose, colorful mantas, tied with a woven belt, high deerskin wrapped boots, or just plain stout walking shoes; gay shawls over the head and shoulders, and wearing enough jewelry to stock a trading post.” Despite the fact that the Pueblo people had inhabited the area for centuries, people like Brode considered them “more guests than servants.”32 In reality, the guests were the scientists and their families.

The town of Los Alamos had been created in such haste that the water system remained above ground. During the bitterly cold winter of 1945-1946, the pipes froze and burst. Water was brought to the town by tanker trucks until the weather warmed and the problem could be permanently addressed. By the late 1940s, what had been intended as a temporary facility had become a regular town, albeit a gated community that appeared to be more a suburb of Washington, D.C., than part of rural New Mexico.

Harold D. Walter (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 053110.

By 1954, debates ensued within Los Alamos and the surrounding region about when the guard station and outer security fences might come down. Within four years of the war’s end similar fences at the atomic towns of Oak Ridge and Hanford had been dismantled. Residents of Los Alamos, however, opposed such a move. Fears occasioned by the nuclear age and the cohesiveness of the small community that had formed there over the past decade played a role in that sentiment.

People in the surrounding region saw the fences as an outward extension of the segregation that existed among workers at LANL and in the housing arrangements in Los Alamos. Those who performed the service work at the labs lived in the less desirable housing developments, while scientists and administrators lived in the newer, more luxurious homes. Residential arrangements outlined the hierarchy of race and class within the town as well as between Los Alamos and surrounding communities.

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

Carlos Vásquez was twelve years old when his family moved to Los Alamos from Santa Fe in 1956. He immediately noticed that that question “Where do you live?” served as a marker of what work a person did, and by extension, his or her level of education and wealth. Susan Tiano was also a child in Los Alamos. Her father operated one of the only private businesses in town. Even after the war, the Atomic Energy Commission maintained control over the town layout, including who lived where and who could operate commercial enterprises. Due to her father’s status as a merchant, Tiano’s family was not eligible to live in the newer homes enjoyed by the scientists—no matter his ability to pay.

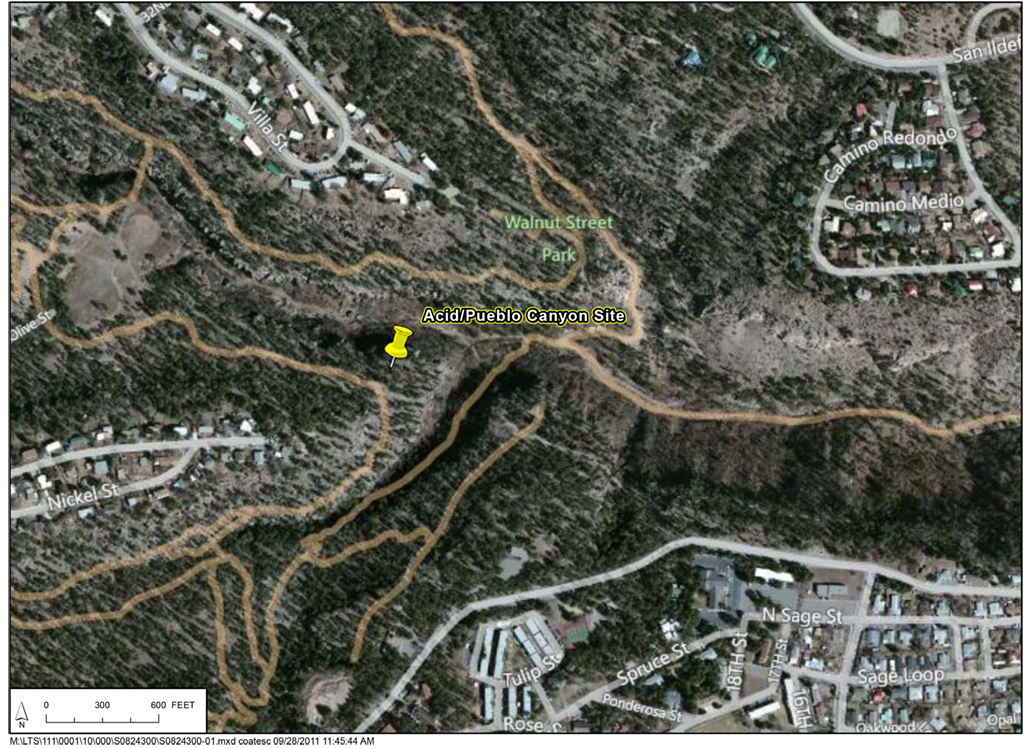

Outside of Los Alamos, hundreds of residents of towns like Española, Pojoaque, and Truchas in Rio Arriba and Santa Fe Counties secured employment at the labs in supporting roles. The vast majority maintained their existing homes and commuted to work on the Hill. As had been the case during the war, nuevomexicanos and Pueblos performed the labor required to maintain day-to-day operations at LANL. Their work included the disposal of nuclear waste, which was initially dumped into the environment at places like Bayo Canyon and many others.

Nuclear contamination in local landscapes is a well-known fact. During the 1950s and 1960s, scientists performed a series of 254 Radioactive Lanthanum (RaLa) tests which released high levels of radiation into the air. Prevailing winds carried the fallout into the valleys where Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Española, and Chimayó are located. The Pueblos and community members were never notified of such tests, and documents which evaluated the costs of the RaLa experiments predicted that the fallout would “move east into ‘unpopulated areas.’”33 But it did not.

Since that time, the residents of the region have experienced high atypical incidences of thyroid cancer and other ailments. LANL officials have initiated several different campaigns to clean the local environment, but Santa Clara and San Ildefonso tribal councils maintain their own surveys of their lands to check for nuclear contamination. Portions of the Pueblos located nearest to the test areas and disposal zones remain highly contaminated. Tribal councils prohibit community members from inhabiting such areas.

LANL has promoted its continued presence in northern New Mexico in terms of its recent positive contributions to scientific research and environmental restoration. Additionally, lab officials underscore LANL’s crucial economic contribution to the region. People like Joe Montoya, a native of Truchas and thirty-five-year LANL employee until his death from Thyroid cancer, touted the labs as “the best job in the state.”34 Without the lab, most nuevomexicanos would be unable to find jobs that provide health benefits or a regular salary.

His daughter, Paula, on the other hand, sees LANL as an industry that has taken far more from northern New Mexico than it has given its people. She is also an employee of the labs, but she feels far more conflicted about her work there. In describing Los Alamos, she uses the metaphor of a bad boyfriend:

You enter into [a relationship with] it seeing all the possibilities, but then it doesn’t live up to your expectations and even though you know it’s bad, it gives you something, you can’t get out, you can’t see another way. . . . You think it’s better than nothing, and maybe it is. That’s why I still work there. What’s worse is that he can never tell the truth and he always has an excuse, he’s never wrong, never responsible, sometimes cute, ultimately painful.35

The relationship between Los Alamos and surrounding New Mexican communities, then, is deeply conflicted, one borne of necessity and mutual, although highly unequal, reliance.

Paula Montoya is sure of LANL’s negative impact on the local environment and cultures, but her father continued his staunch support of the labs until the day he died. Early in his career, he personally dumped radioactive waste into surrounding canyons, including the one that has become known as “acid canyon.” Later in life, he realized that such actions were destructive, but reasoned, “we just didn’t know better. It was ‘out of sight, out of mind.’”36

Courtesy of U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management

His wife Flora understood the benefits and costs of work at Los Alamos, yet, like her husband, she was unwilling to deny the economic value of work at the labs. She and many others in her community know that the high rates of cancer are the result of work performed at LANL. But, in another sense, due to the invisible nature of radiation, “it’s hard to know for sure.”37

The legacy of the Manhattan Project is quite mixed in northern New Mexico. Families remain deeply divided about whether or not LANL has been a boon to their way of life. LANL’s continued presence provides the economic backbone of the New Mexican villages that were the focus of the earlier movement to preserve their unique cultures. But the Manhattan Project and the laboratory represent a different way of life. Somewhat paradoxically, LANL promises to support village economies while simultaneously altering nuevomexicano and Pueblo patterns of living.

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

More broadly, the World War II era changed New Mexico and the West in profound ways. The rise of the military-industrial complex altered western landscapes and helped to free the region from economic domination by points in the eastern United States. The war also initiated massive migration from East to West to support facilities like LANL, Sandia National Laboratories, Kirtland Air Force Base, Cannon Air Force Base, and the White Sands Missile Range.

Within New Mexico migration from rural areas to cities, like Albuquerque, Santa Fe, or Las Cruces, increased as federal funding for the war effort poured into the state. New Mexico remains among the states that receive the highest level of per-capita federal spending in the nation, a reality that helps to secure the state’s economy. Additionally, the Forest Service and Bureau of Reclamation draw federal funds to New Mexico.

Even as New Mexico became a focal point for the Cold War nuclear arms race, many of its people were estranged from the benefits of the military-industrial complex. Nuevomexicanos, Pueblos, Navajos, Apaches, African Americans, and women all participated in the various civil rights movements that began in the 1950s.