Part 2: Chapter 9

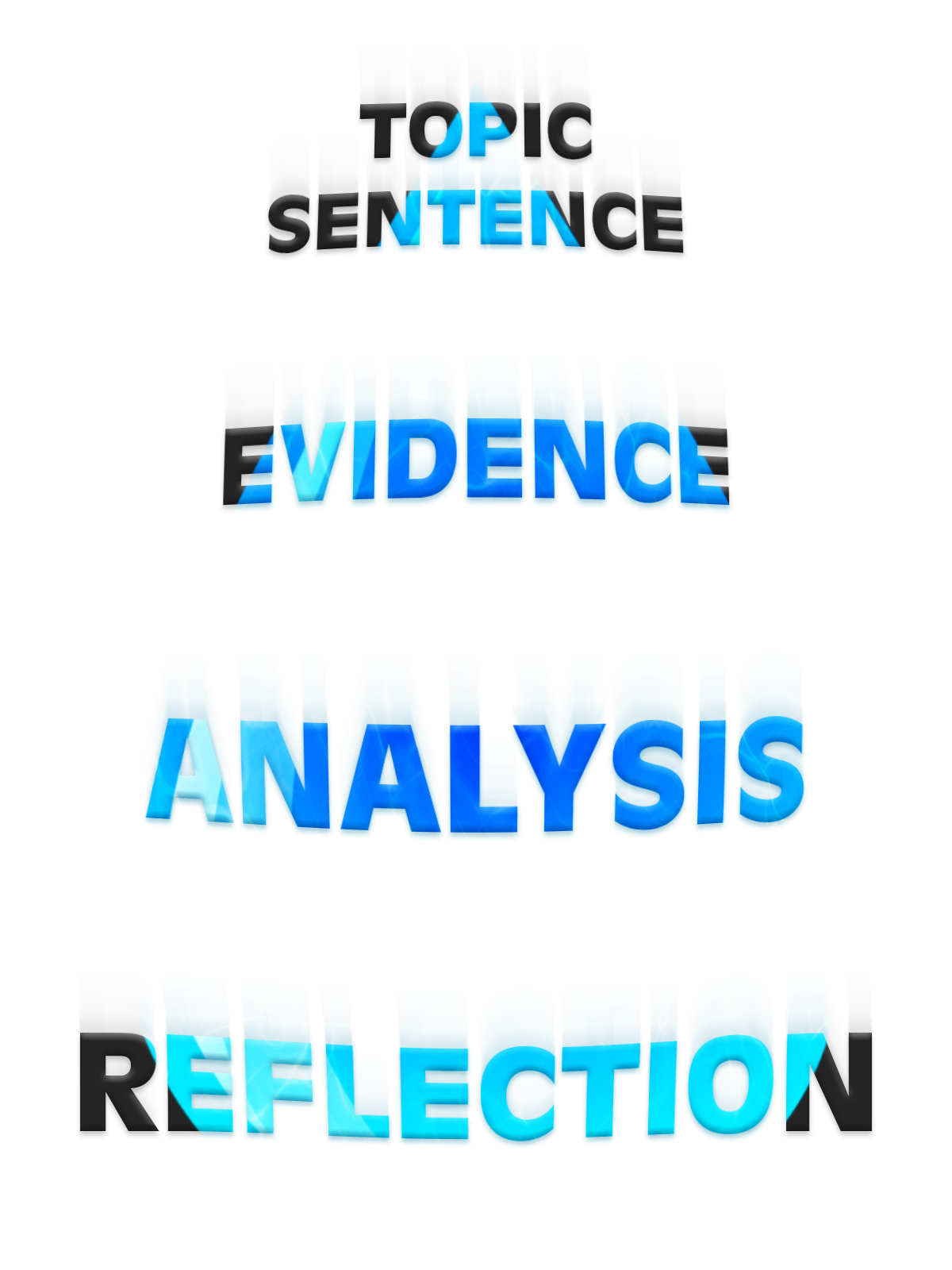

We have looked at the basic parts of your essay, and now we have a sample formula to help you expand your ideas about your evidence. Between the Introduction (and thesis) and the Conclusion (and reflection on the thesis) comes the body of the essay. For your essay’s body to be solid and focused, it needs to have clear, well-developed paragraphs. Even paragraphs need to have a beginning, middle, and end. To help you think about paragraph organization, think about TEAR:

T = Topic Sentence

This is like a little thesis for your paragraph. It tells the reader what that paragraph is all about. If your reader were only to read the topic sentences in your essay, he/or she should have a general idea of what you’re talking about. Of course, he/she can’t get a complete picture unless you provide…

E = Evidence

This is the “how do you know?” part of your paragraph. Evidence comes from the real world. You may present your evidence in the form of statistics, direct quotes, summaries, or paraphrases from a source, or your own observations. Evidence is available to us all. What your reader needs is for you to make sense of that evidence so that s/he understands what all this has to do with your thesis or claim. That is why you provide…

A = Analysis

This is the ‘so what?’ part of your paragraph. You say what is important and why. This isn’t just personal taste or opinion. You have to provide good reasons to support your conclusions. And just to make sure you’re still on track, you…

R = Reflection

This sentence concludes the paragraph, relates to the topic sentence and the thesis. Ideally, it should also prepare us for the next paragraph.

To help you think about TEAR, imagine your snarky little brother looking over your shoulder as you compose asking you:

T = “What’s all this about?”

E = “How do you know?”

A = “Why should I care?”

R = “What does this have to do with anything?”

You may be thinking, I’ve heard this before, but it wasn’t called TEAR. It was called….

PIE

What does PIE stand for?

P = Point. This is the point of the paragraph, or the topic sentence.

I = Illustration. This is where you illustrate your point with evidence

E = Explication. This is where you explain how that evidence supports your point. This is your analysis.

Why give you two ways to think of this? Because you may find that to fully develop your paragraph, you’ll need to add a little more evidence and analysis. And it looks a little funny to write TEAEAR. So, you can think of PIE-IE-IE will always love you.

Take a look at the picture above. Notice anything? No two slices are the same. So it should be in your essay. Each paragraph should do its own job, have its own focus. Sure, your essay may feature a variety of related paragraphs grouped in sections; however, to avoid repeating information or losing focus in your essay, remember that each slice of PIE should serve a unique purpose.

–the above writing was adapted from a handout created by the talented and brilliant CNM English instructor, Patricia O’Connor.

Varying Sentence Structure

Argumentation isn’t just about what you say, it’s also about how you say it. Even the most solid argument won’t get far with a reader if the text isn’t engaging. But how do we make it so?

Perhaps the biggest secret to creating captivating writing is variation. Without it, your reader might fall asleep from boredom.

If you’ve ever been in a vibrant debate with someone you respected about beliefs you hold dear, you’ve got a sense of just the kind of life we want to capture when we’re writing. Learning, debating ideas, digging for the truth: these things are all fun! No need for “anyone” to be drooling on his desk.

If variation is key, what can we vary? We’ve discussed the importance of structure. Readers need to depend on the paper’s structure to be able to follow the argument. So, introduction, conclusion, body paragraphs with topic sentences and transitions—yes to all of these. Within the structure, though, you can vary the following:

-

sentence length

-

sentence structure

-

sentence type

-

tone

-

vocabulary

-

transition words and categories

-

types of evidence

You’ll want to have reasons for the choices you make. Adding random rhetorical questions will sound strange, but if you ask the right question at the right time, it will make the reader think. The same will be true of all variation. There must be a good reason to choose a particular sentence structure or a new type of evidence.

There are no codified rules on how to vary sentence structure, nor are there lists of all the different types of phrasing you can use. The English language allows for so much flexibility that such a list would be never-ending. However, you should consider certain aspects of writing when looking for different sentence formats.

Clauses: The easiest way to vary sentence length and structure is with clauses. Multi-clause sentences can connect related ideas, provide additional detail, and vary the pattern of your language.

Length: Longer sentences are better suited for expressing complex thoughts. Shorter sentences, in contrast, are useful when you want to emphasize a concise point. Clauses can vary in length, too.

Interrogatives: When used sparingly, questions can catch your reader’s attention. They also implicate your reader as a participant in your argument by asking them to think about how they would answer the question.

Tone: If you want a sentence to stand out, you can change the tone of your writing. Using different tones can catch the reader’s attention and liven up your work. That means you can be playful with your reader at times, sound demanding at times, and cultivate empathy when that feels appropriate. Be careful that the tone you choose is appropriate for the subject matter.

Syntax variation cultivates interest. Start playing with structure. Try changing a sentence’s language to make it sound different than the ones around it.

Syntactical Variation

Here is an example of what a paragraph with a repetitive syntax can sound like:

“Looking Backward was popular in the late nineteenth century. Middle-class Americans liked its vision of society. The vision appealed to their consumption habits. Also, they liked the possibility of not being bothered by the poor.”

Choppy? Uninteresting? Here’s the rewritten version, with attention paid to sentence variation:

“The popularity of Looking Backward among middle-class Americans in the late nineteenth century can be traced to its vision of society. The novel presents a society that easily dispels the nuisance of poverty and working-class strife while maintaining the pleasure of middle-class consumptive habits.”

What’s different here? The rewrite simply combines the first two and the last two sentences and adds a bit of variation in vocabulary, but the difference is powerful. Of course, if all the sentences were compound like these, the paper would begin to sound either pretentious or exhausting. If this were your paper, you might want to make the next sentence a short one and get to your thesis statement relatively soon.

Varying Vocabulary

One way to avoid appearing overly repetitive is to consult a thesaurus and use synonyms. However, when using synonyms, you should make sure that the word you choose means exactly what you think it means. (“Penultimate,” for example, does not mean “the highest,” and there’s a difference between “elicit” and “illicit.”) Check the connotations of synonyms by looking up their definitions.

Varying Transitions, Signal Words, Pointing Words, and Pronouns

Writers familiar with their own habits will sometimes do a “word search” on a word or phrase they typically overuse (“however,” “that said,” “moreover,”) and replace some of those words with another transition. Or they might rework a sentence to avoid using any transition words in that spot, if they feel they’re overdoing it. Nouns, too, are often overused when pronouns would sound more natural. Don’t worry about this too much in the writing phase; you just want to get your thoughts on the page. But as you revise, keep an eye out for repetitiveness and vary your sentence constructions to keep your paper interesting.

Introducing variation benefits not only your reader, but also you, the writer. Conceiving of different ways to communicate essential elements of your argument will allow you to revisit what makes these elements essential, and to consider the central argument you are making. Each variation is a chance to introduce nuance into your writing while driving your point home. However, variation should never be your main goal—don’t sacrifice audience comprehension to achieve stylistic virtuosity. You’ll just sound silly. The argument is the point.

Adapted from “Chapter Seven” of Boundless Writing, 2015, used under creative commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Adapted from “Chapter 7” of Writing, 2015, used under creative commons CC-BY-SA 4.0