The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 12: Statehood Achieved & Loyalty Questioned: the World War I Era

- Statehood Achieved & Loyalty Questioned: the World War I Era

- Statehood Finally Arrives

- "Loyalty Questioned": Revolution & War

- References & Further Reading

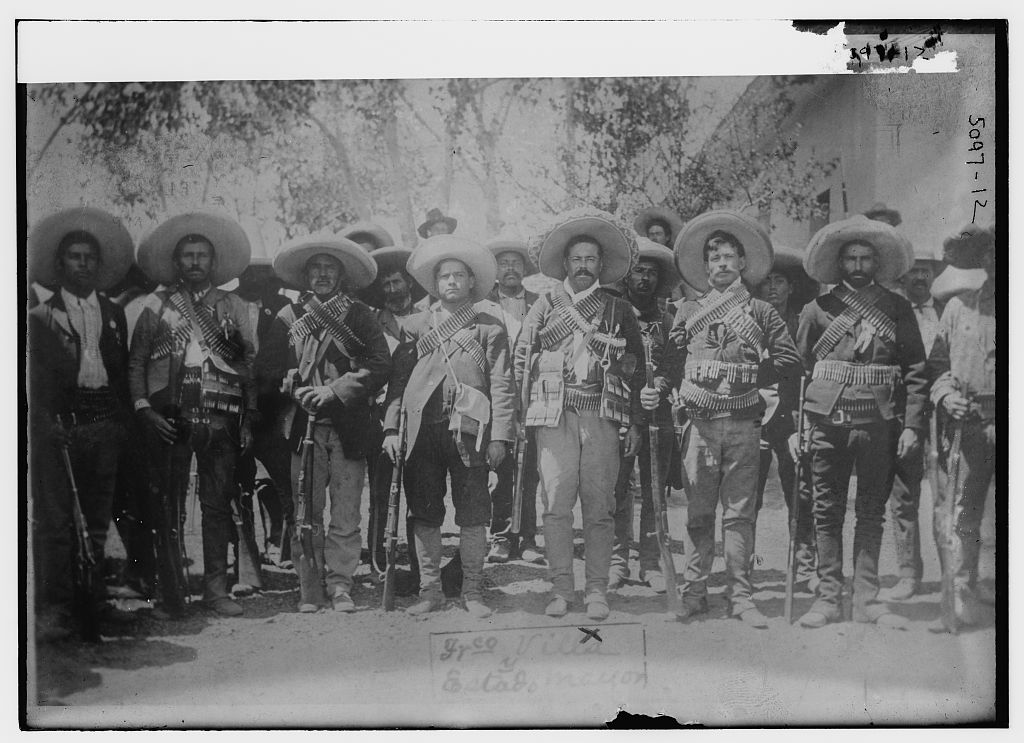

At sundown on the evening of March 1, 1916, Maud Wright rushed outside of her ranch home about thirty miles distant from the American-dominated town of Pearson, Chihuahua, in the Sierra Madres. She had expected to see her husband, Ed, and his business-partner Frank Hayden. Instead, she found a group of nearly fifty Mexican soldiers associated with the infamous General Francisco “Pancho” Villa. The Mexican Revolution, a decade-long civil war that reconfigured political leadership and social relations, was at high pitch, so she may not have been surprised. Still, the band of soldiers was disconcerting.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Just a few years earlier, Maud had left her family’s ranch at Pinos Altos, New Mexico—located in the heart of Chiricahua ancestral homelands—with Ed. Lacking her father’s blessing, the pair eloped to El Paso and were married on January 10, 1910. They made their home at Pearson (today the village of Juan Mata Ortíz), where Ed operated a ranch. With Hayden and a large number of local chihuahuense (residents of Chihuahua) laborers, he opened a sawmill.

Due to the violence of the Mexican Revolution, which had begun in November 1910 with the most intense fighting near the border with the United States, the Wrights and over 1,000 other Americans (mostly Mormon colonists who also lived in the Sierra Madres) fled across the border in the summer of 1912. Ed found work on sawmills and cattle ranches in southern New Mexico for the period of a little over a year. During their self-imposed exile, in the spring of 1914, Maud gave birth to a son, Jonnie. That fall, the family returned to their lands in Chihuahua, as did a small group of the Mormon colonists.

Violence between various revolutionary factions continued as the Wrights attempted to reestablish their ranch and mill. By early 1916, Villa retreated to Chihuahua in response to a series of devastating defeats at the hands of erstwhile revolutionary ally, Alvaro Obregón who led the forces of de-facto President Venustiano Carranza. The previous November had marked Villa’s most devastating defeat yet at the Battle of Agua Prieta on the Arizona-Sonora border. On that occasion, President Woodrow Wilson had allowed carrancista troops (those allied with Carranza) to travel between El Paso, Texas, and Douglas, Arizona, on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Wilson had previously made positive overtures to Villa, and the battered general considered his actions a calculated betrayal.

Clifford Berryman’s editorial cartoon published in U.S. newspapers following Villa’s raid on Columbus in March 1916. The cartoon illustrates the Wilson administration’s decision to dispatch troops into Mexico in pursuit of Villa.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

The villista (forces under Pancho Villa) unit that congregated outside of the Wright’s home on March 1, therefore, had been tempered by their general’s call to kill all Americans. Maud tried to pacify the hungry soldiers by offering them food, but when her husband and Hayden returned with loaded pack mules the villistas looted and sacked the house. After forcing Maud to hand her toddler son over to a Mexican domestic servant, she mounted a horse and followed the party, along with her husband and Hayden, as a captive.

After two days of marching, soldiers took Ed Wright and Frank Hayden aside, out of Maud’s view, where they were executed. Despite the compounded hardships of her husband’s murder and traveling with the villistas who scarcely had enough food for themselves, much less a captive, Maud remained resilient. Shortly after the party of soldiers joined the main body of villistas, which included a total of nearly five hundred men, General Villa ordered one of his captains to keep watch over Maud. He gave the captain specific instructions that she not be harmed. Her guard, Juan Ramón Ruíz, spoke fluent English and abided by Villa’s command. Ruíz even reprimanded and threatened to report any men who so much as swore in Maud’s presence.

Over the next several days, Maud silently endured the loss of her husband and the separation from her son, as well as her hunger pains. The villistas rode continuously. From her observations, most of the men seemed to fear Villa. Their conversations immediately hushed any time that he rode near. Since Villa’s string of defeats in 1915, many of his famed Dorados (the Golden Ones, his elite fighting unit), had either been killed or abandoned his cause. Now, those under his command, with the exception of a few captains, had been forced into service at the threat of physical harm to themselves or members of their families.

As the group passed through lands controlled by the Palomas Land and Cattle Company, less than fifty miles south of the New Mexico-Chihuahua border, they happened upon a group of cowboys who were engaged in a cattle roundup. Two of them were captured, and Maud witnessed their torture and execution by hanging. She often wondered why Villa had not killed her, and she asked him as much in one of the few occasions that he spoke with her. He told her that if she survived the march to their next offensive, he would set her free. By the tone of his voice, she could tell that he did not expect her to withstand the long advance on horseback with little food or water.

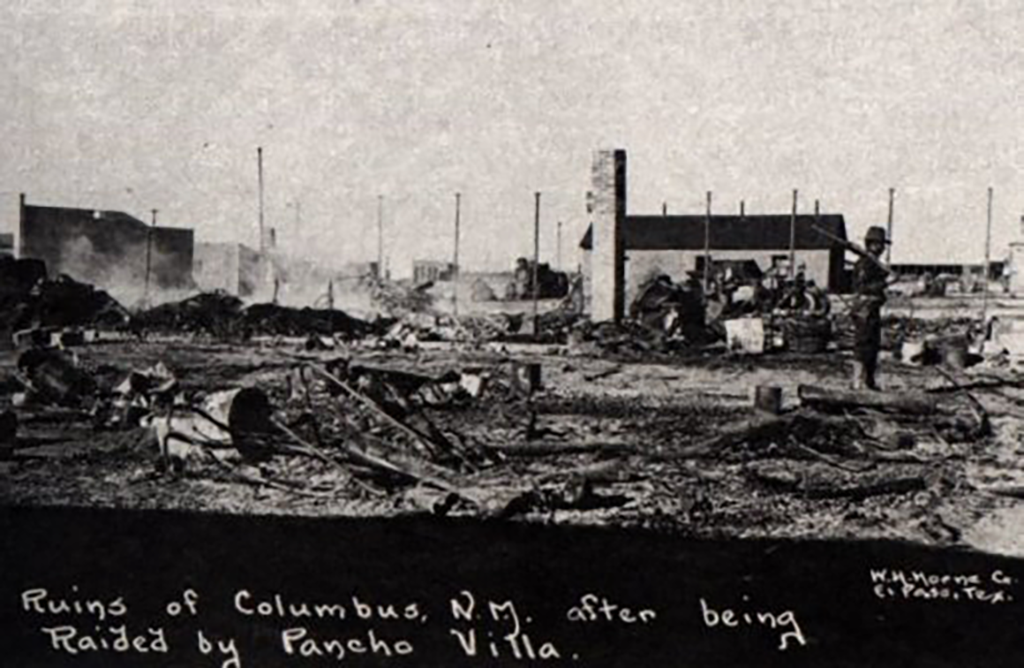

She did survive, however, and she witnessed the villistas’ infamous raid on the sleeping town of Columbus, New Mexico, in the early hours of March 9. Although the attack was a strategic victory for Villa, it was a tactical blunder. Based on faulty intelligence, his men fired on the stables rather than the barracks at the U.S. Military camp that housed the 13th Cavalry. Members of the 13th awoke to the sound of the villistas’ weapons and they scrambled to mount a defense. The advantage of darkness was lost when a group of villistas set fire to the Commercial Hotel in the Columbus business district. After only a couple hours of fighting in the streets, Villa and his men were forced to retreat into Chihuahua. Nearly one hundred villistas were killed, compared to eighteen Americans.1

Courtesy of Tatehuari

Maud Wright’s harrowing experience and Villa’s attack on the tiny border town of Columbus were part of an era in which residents of the newly minted state still struggled to prove their loyalty as American citizens, and most New Mexicans battled ongoing poverty. The Columbus raid projected New Mexico onto the national stage once again only four years after it gained brief notoriety for finally receiving admittance to the Union as a state.

Statehood was achieved through a series of political dealings in Congress, and residents of New Mexico were left to confront problems that had long-characterized their daily lives, including poverty, discrimination, lack of educational resources, and governmental corruption. In March 1916, New Mexico became a source of national outrage for Americans across the country due to Villa’s brazen attack on U.S. soil. Still, nuevomexicanos themselves remained suspect. Units of the New Mexico National Guard organized and relocated to the border in response to President Wilson’s mobilization of U.S. forces to pursue Pancho Villa into Chihuahua. They were joined by National Guard and regular U.S. Army units from around the nation. At that time, the New Mexico National Guard was about sixty-percent hispano.

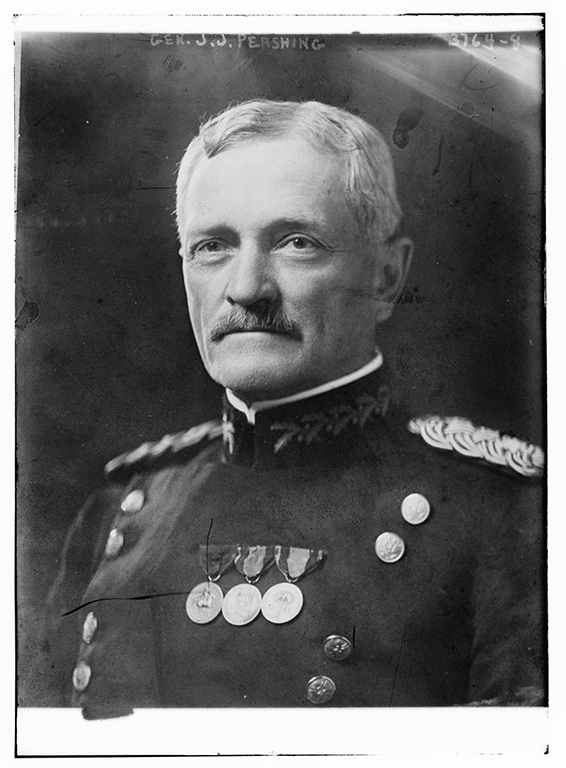

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The campaign was led by General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, and has been historically remembered as the Pershing Punitive Expedition. Although Pershing’s forces failed to apprehend Villa, their experiences comprised what historians later characterized as a “dress rehearsal” for U.S. participation in World War I. During the Punitive Expedition, it became clear that the U.S. Army was ill-prepared for war, and Pershing (who led the American Expeditionary Force in 1917 and 1918) initiated an extensive training campaign before he committed any American forces to the conflict in Europe.

Despite their willingness to serve in the conflict precipitated by the Mexican Revolution, New Mexican National Guard units faced discrimination and disparagement as they supported the U.S. military effort on the border and in Chihuahua. Participation in the World War I effort was once again a means for nuevomexicano recruits to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States, as had been the case in earlier conflicts like the Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Civil War. New Mexico’s first years as a full-fledged state were tempered by the paradox that it was still marked as not yet on par with the rest of the nation in terms of culture, religion, language, and modern capitalist modes of labor and production.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration