The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 12: Statehood Achieved & Loyalty Questioned: the World War I Era

- Statehood Achieved & Loyalty Questioned: the World War I Era

- Statehood Finally Arrives

- "Loyalty Questioned": Revolution & War

- References & Further Reading

This chapter provides a culmination of the discussions in Chapters 9, 10, and 11 regarding territorial struggles with an eye toward statehood. Although many of the various social, economic, and political movements of the territorial period can (and should) be considered independently of the push for statehood, the desire to realize the prospect of full citizenship rights in the Union through statehood was the overarching political concern of the period between 1848 and 1912.

On its face, the statehood struggle was a painful, sixty-four year process that was tightly connected to the themes of modernization and Americanization, as well as the development of Spanish American ethnic identity and debates over the role of the Spanish language in New Mexico. Political intrigues and ethnic prejudices were the principal reasons for the delay in New Mexico’s statehood. Statehood was postponed for a variety of reasons, but the fact remains that one of the easiest ways for U.S. politicians in the East to prevent former Mexican citizens from full inclusion in the United States was to maintain New Mexico’s territorial status.

Early in the statehood struggle Major John Monroe, who served as New Mexico Territorial Governor in 1850, wrote to his superiors in Washington, D.C., that nuevomexicanos’ loyalties lay with the Mexican government. Claims like his signaled to the federal government that New Mexicans posed a threat to U.S. sovereignty in the Southwest. Following Monroe’s line of reasoning, not until New Mexicans proved their loyalty to United States would the territory be admitted into the Union.

In fact, a pro-statehood movement began almost immediately after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo solemnized New Mexico’s transfer to the United States. As the situation stood in the early 1850s, New Mexico already met the population requirement for statehood that dated back to the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. President Zachary Taylor, who gained a reputation for unswerving military discipline through his leadership during the U.S.-Mexican War, wanted to bring New Mexico and California into the Union as free states as quickly as possible in order to avoid sectional conflicts in Congress that promised to pit Northern and Southern legislators against one another.

To that end, Taylor dispatched Major George McCall to the territory with instructions to help local politicians organize a statehood convention and draft a constitution. McCall was successful on both counts by early 1850, but the politics of slavery intervened to kill New Mexico’s first statehood initiative. Southern politicians vocally opposed New Mexico’s entry as a free state, and they threatened to derail statehood for California as well until the Compromise of 1850 narrowly averted that outcome. Under the terms of the deal, New Mexico’s bid for statehood was tabled.

New Mexico’s various delegates to Congress, including Miguel A. Otero and Stephen B. Elkins (a close friend of Thomas B. Catron), clearly understood that the most pressing issue on their agenda was the promotion of statehood. The three principal requirements for a territory to become a state were a minimum population threshold (which ranged between 60,000 and 90,000 as congressional stipulations changed over the last half of the nineteenth century), the creation of a constitution at a statewide convention, and the approval of both houses of the U.S. Congress by a simple majority vote. New Mexico’s delegates knew well that congressional approval was the only element that prevented their territory from becoming a state.

Otero and Elkins worked tirelessly during their respective tenures in Washington, D.C., to amass support among as many congressmen as possible. The controversy over Otero’s support of New Mexico’s 1859 Slave Code was tied to his desire to garner statehood votes from Southern lawmakers. In 1876 Elkins unwittingly committed a faux pas that illustrated just how fickle political support could be. During one particularly heated debate, Michigan Representative Julius C. Burrows gave a fiery oration in support of a civil rights bill geared toward African Americans. Following the speech, Elkins shook hands with Burrows in congratulations for his remarks. Several Southern Representatives noticed the gesture and pulled their support for New Mexico’s statehood as a result.

During the 1870s and 1880s, the political chicanery of the Santa Fe Ring and Wild West reputation of Billy the Kid marked New Mexico as ill-prepared for statehood. Governor L. Bradford Prince’s editorials in the New York Times mentioned in Chapter 10 were intended to undo the negative press that regularly circulated regarding the territory.

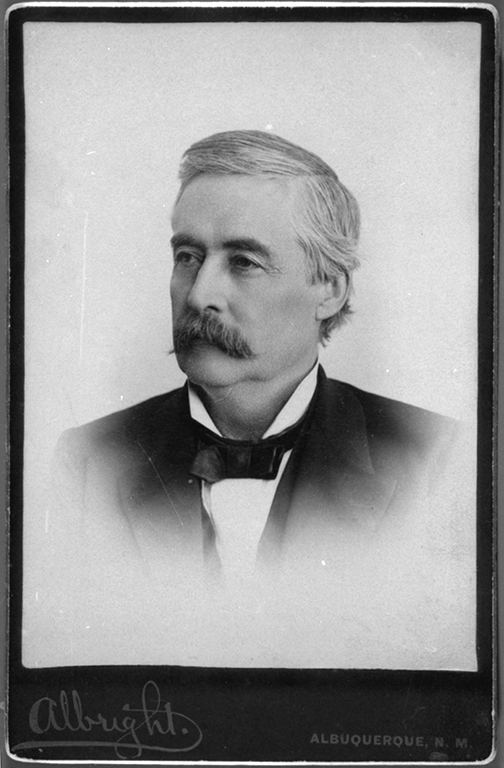

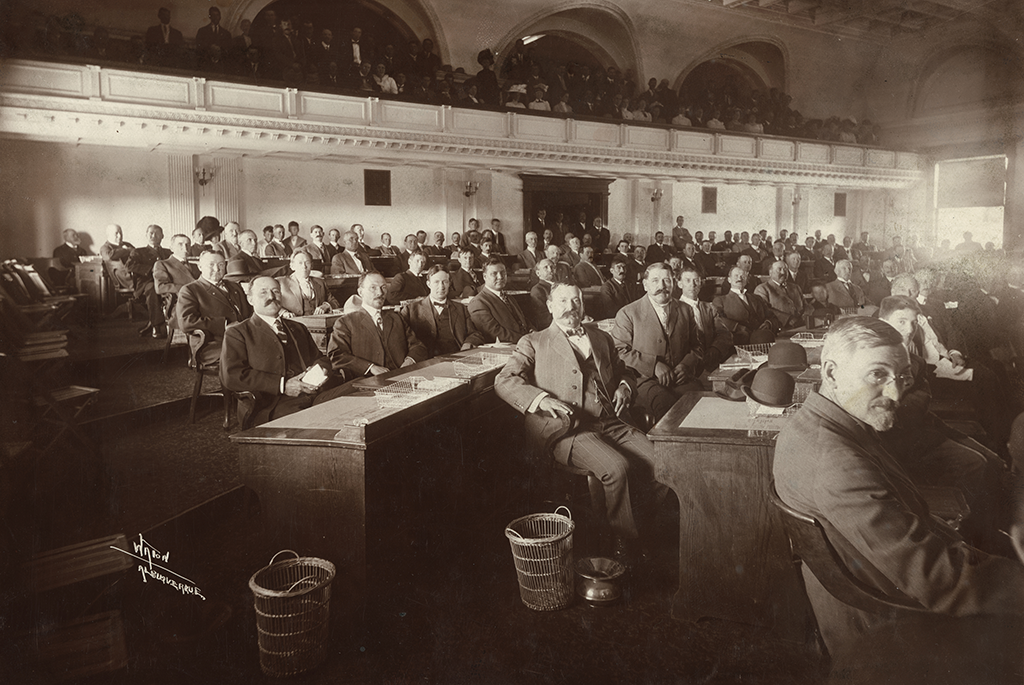

Albright Art Parlors (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 049253.

Prince’s tenure as governor followed Democrat Edmund G. Ross, who dedicated his governorship to limiting the power of the Santa Fe Ring. Despite his best efforts, including a plan to gerrymander territorial voting districts, Ross’ tenure resulted in legislative gridlock as the Ring asserted its political power. In 1889, Republican President Benjamin Harrison appointed Prince as the replacement for Ross. Although there are no strong indications that Prince was in the pocket of the Ring, his politics were more acceptable for their intense focus on capitalist development and business interests.

Due to his visibility in the national press, Prince served as an important statehood advocate. In 1889 he supported a new constitutional convention that was held in Santa Fe. As had so often been the case, the convention was dominated by delegates tied to the Ring and the group drafted a highly conservative constitution. Among its provisions were extremely low property taxes (never to exceed one percent), state funding for secular schools (at the expense of Catholic-run parochial schools), and an article that required all court proceedings to be carried out in English. All of those measures promised to promote Catron’s control over territorial lands and resources.

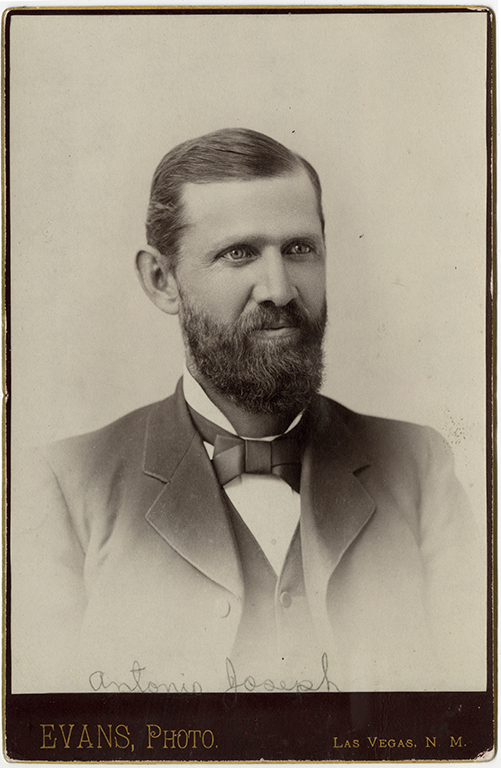

Evans (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 009915.

Residents of the territory opposed the proposed constitution when it was put to a vote. Despite Governor Prince’s dedication and his close association with congressional delegate Antonio Joseph to advocate for statehood at the national level, Congress generally maintained the belief that New Mexicans were anything but unified in their support of statehood. Residents of the territory were divided along partisan and ethnic lines over the terms under which New Mexico would become a state. Among the most prominent sticking points was a provision in the 1889 constitution that prohibited the use of Spanish in official matters, including court cases, primary schooling, and voting.

Anglo Americans, particularly large landholders in southeastern New Mexico, refused to accept a state constitution unless it specified the exclusive use of English in state political and legal business. Most of them were supporters of the Democratic Party, whose platform reflected their views. Republicans, on the other hand, countered that no such provision was needed because statehood would naturally bring new immigrants from the Eastern United States and the widespread use of English would eventually develop on its own.

Territorial Republican officials might have secured the votes of nuevomexicanos (only men were permitted to vote at the time) for a constitution without the language stipulations, but their views on public education prevented such an outcome. Republicans supported an initiative to teach nuevomexicano children to speak English through the proposed state-run primary education system. Catholic officials, who had presided over education in the region since Spanish-colonial times, opposed any such measure and most devout hispanos sided with them. When the 1889 was put to a territorial vote, then, it was handily defeated 16,180 votes to 7,493.2

Delegate Joseph spearheaded several different attempts at statehood during the 1890s, but the idea that nuevomexicanos were incapable of self-government persisted among many congressmen. In an effort to revise their understanding of New Mexico and its peoples, La Voz del Pueblo (Las Vegas) published a series of Spanish-language articles penned by hispano men and women across the territory and in southern Colorado who held a very different understanding of New Mexico’s readiness for full inclusion in the United States.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 050461.

Colorado legislator Casmiro Barela and Santa Fe constitutional delegate José D. Sena led the editorial charge. In response to the claim that nuevomexicanos were “easily manipulated” and “ignorant” by virtue of their mixed ethnic background, Barela wrote, “I reject that accusation with disdain.” He continued, “Since 1848, the Mexican population has advanced in education, in independence, in mental vigor, and in firm loyalty to the American government.”3 To further his arguments, Barela emphasized the territory’s 2,000 miles of railroads, various mines, large-scale agricultural production, and educational advances.

Similarly, Sena touted the ways in which New Mexico had embraced the project of modernization. Taking a unique approach in the era of Spanish-American Ethnic Identity, he also drew upon the precedents of the history of Mexican independence to show that nuevomexicanos were no strangers to systems of representative government. Sena argued, “It is an insult to the descendants of Hidalgo, Morelos, and Iturbide when the opponents of statehood say ‘we’ are not fit to govern ourselves.” As he and other nuevomexicanos knew well, their forebears had a long tradition of independent local governance through ayuntamientos. The often-cited idea that they were incapable of self-governance, therefore, made no sense.

In Washington, D.C., delegate Antonio Joseph attempted to draw the distinction that nuevomexicanos were ethnically “Spanish” in an effort to diminish the widely held belief that New Mexicans were unfit for republican governance. Such notions can be traced back to the comments made by Senator John C. Calhoun, as mentioned in Chapter 8, but also to the remarks of Daniel Webster. Although a staunch opponent of slavery, like most other Northerners Webster was convinced that Mexicans were racially inferior to Anglo Americans. By adding them to the Union, he feared that the foundations of representative government would be eroded.

Accordingly, historian David V. Holtby frames his recent study of New Mexico’s statehood struggle in terms of the larger political and economic context of the United States.4 Such an approach is particularly valid because, in the end, the concerns of territorial officials and residents were eclipsed by the agenda of the U.S. Congress. In other words, no matter what New Mexicans did to promote statehood, ultimately the decision to admit the territory to the union lay with Congress and the President.

Holtby’s analysis does not minimize the very real battles waged in the territory over issues such as Spanish-language instruction in primary schools, a continued political role for nuevomexicanos, and competing images of New Mexico as the center of the Wild West and a burgeoning site of modern enterprise. Such conflicts shaped the type of constitution that was finally accepted by Congress in 1910, and they influenced the ways in which New Mexicans understood their place in the United States. Yet the reality was that without the approval of the federal government, territorial debates over the shape that the state would take were meaningless.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, the reality that statehood was the purview of Congress was indelibly etched in the minds of New Mexican powerbrokers. At the national level, political divisions were rife. Advocates of federal power competed against those who promoted states’ rights, Progressives sought to root out political corruption and rise above political mudslinging, and the emergence of competing forms of capitalism (including mercantile—or small-scale, finance, and corporate capitalism) altered the terms by which New Mexico became a state. Indeed, statehood was finally achieved in smoky rooms behind closed doors in an anticlimactic way, especially to those who had dedicated so much of their blood and sweat to the cause at the regional level.

Between 1900 and 1912, New Mexico’s policy makers made the final, successful push for statehood. The separate campaigns for New Mexico’s and Arizona’s inclusion in the Union were the longest in U.S. history. As Holtby, Robert W. Larson,5 and many others have illustrated, the political scene in the first decade of the twentieth century further complicated matters. On the heels of the Spanish-Cuban-American War, Eastern politicians often conflated New Mexico and Arizona with the newly acquired territory of Puerto Rico. All were considered foreign and ill-prepared for inclusion in U.S. governance at best, and potentially traitorous at worst.

Despite the prevailing attitudes in the Eastern United States, nuevomexicanos like Aurora Lucero, quoted in Chapter 11, continued to advance the argument that New Mexico’s people had always been loyal citizens. New Mexicans had indeed proven their loyalty to the United States in various conflicts dating back to the Civil War. Hundreds of nuevomexicanos had enlisted with Teddy Roosevelt’s’ Rough Riders. Still, the loyalties of nuevomexicanos remained suspect.

New Mexico’s final push for statehood came at the height of the Progressive Era in U.S. national politics. Progressives advocated for diverse political, social, and economic concerns, and figures who considered themselves part of the movement belonged to both political parties and generally heralded from the middle-class. “Reform” was the Progressive mantra, and its supporters believed that principles of science and efficiency would bring about the correction of the greatest excesses of the Gilded Age. Among Progressives’ varied projects were the eradication of graft and corruption in politics, conservation of forests and natural resources, and the regulation of monopolized industries. As far as where immigrants were concerned, Progressives generally supported Americanization and assimilation measures.

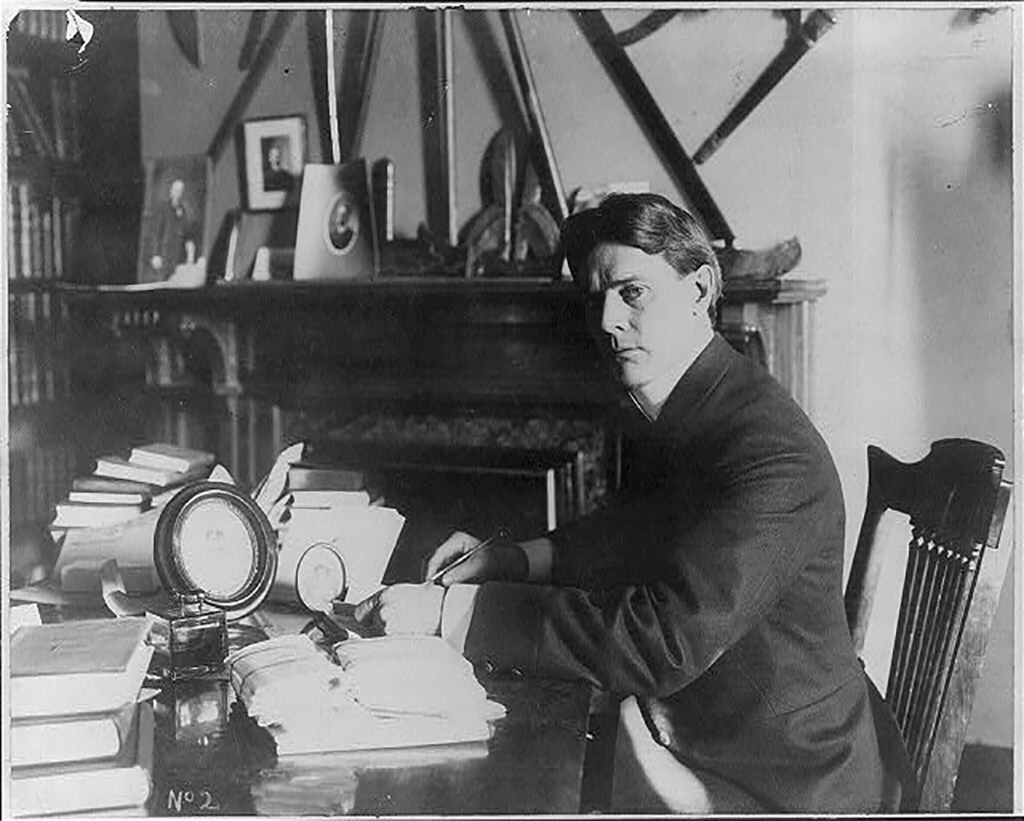

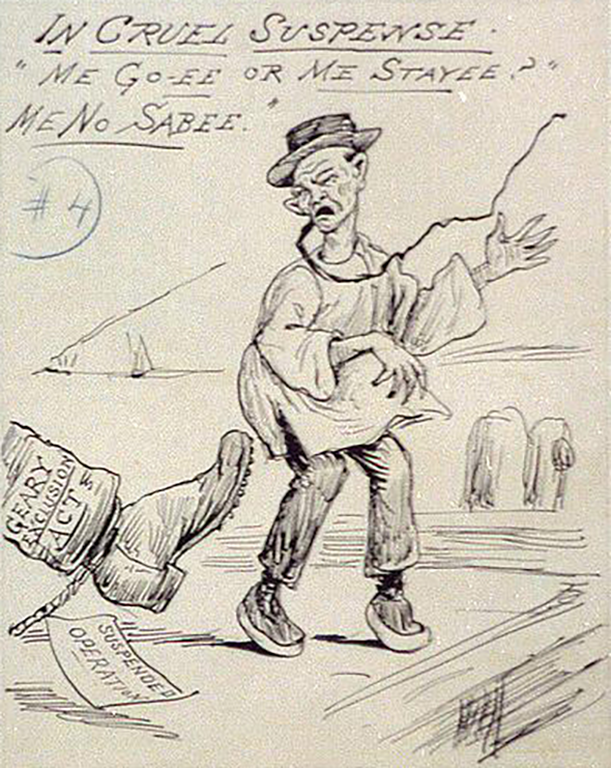

Courtesy of Library of Congress

From the perspective of many Progressives, including Indiana Senator Albert J. Beveridge who headed the Committee on Territories, New Mexico’s peoples and politics disqualified it from statehood.6 Despite a very active period which saw the introduction of more than twenty different statehood bills between 1890 and 1903, New Mexico still remained a territory. One of the most intense periods of congressional debates over statehood thus developed during the final decade before statehood was actually achieved. Senator Beveridge emerged as one of the most strident and vocal opponents of statehood for both New Mexico and Arizona.

Beveridge was a talented orator, dedicated imperialist, and highly active member of the American Historical Association. Following his tenure in the Senate, he wrote a series of well-regarded biographies. During the Spanish-Cuban-American War, he vocally disparaged Spain and its colonies to justify the expansion of U.S. influence abroad. In the process, he promoted Anglo-American nativism at the expense of any who spoke the Spanish language or who had descended from areas formerly dominated by Spanish colonialism. He equated New Mexico’s majority hispano population with what he considered to be the most negative aspects of Spanish society.

As chairman of the Committee on Territories he stalled an omnibus statehood bill that the powerful Pennsylvania Senator Matthew S. Quay had prepared for what promised to be easy passage in 1902. Concerned that the Democratic Party would gain ground in the fledgling states of Arizona and New Mexico, Republican Beveridge tirelessly argued against the readiness of New Mexico’s largely Spanish-speaking populace for full inclusion in the United States.

Beveridge made no attempt to hide his conviction that nuevomexicanos were ill-equipped to participate as U.S. citizens because they were unfamiliar with the nation’s laws, illiterate, and ignorant. The persistence of the Spanish language was also perplexing to him. As he stated in 1910, proposed amendments in the Enabling Bill, including Article 21, were intended to end “the curious continuance of the solidarity of the Spanish-speaking people” in New Mexico. He also characterized nuevomexicanos’ “refusal” to speak English as treason.7

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 158257.

As part of his campaign to prevent the entry of New Mexico and Arizona into the Union, Beveridge proposed a personal investigation of the two territories. With three other Republican Senators, he began his tour of New Mexico in mid-November of 1902. With much fanfare and publicity, his subcommittee conducted various hearings throughout the territories within a period of about three weeks. In Las Cruces, local resident Martinez Amador testified that “his fellow Spanish-Americans were too poor and uneducated for the responsibilities of statehood.”8

Most of the testimony reflected similar ideas. Beveridge’s own correspondence just prior to his tour of the territories shows that he purposely selected witnesses who would support his line of thinking. In a letter to his close friend Albert Shaw, he admitted that he hesitated to call anyone “before his Committee, unless he knew beforehand what their testimony would be.”9 Additionally, all of the hearings were conducted privately—none were open to the public. Beveridge’s questions were disproportionately directed toward issues of literacy, Spanish-language usage, and racial composition of the territory. Such evidence challenged the Senator’s repeated claims of impartiality toward New Mexico.

As usual, nuevomexicanos did not take lightly the accusation that they were not fit for statehood. In the territorial press, statehood proponents retorted that Beveridge’s inquiry was slanted toward painting an unfavorable picture of New Mexico and its people rather than attempting to learn the real state of affairs on the ground.

Back in Washington, D.C., Beveridge published the majority report of his series of hearings and continued to push the argument that New Mexico and Arizona were ill-prepared for statehood. Although he never directly defeated Senator Quay’s attempt to bring Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona into the Union, Beveridge’s efforts were enough to delay statehood in seemingly endless Congressional debates.

Just before his death in late May of 1904, Quay helped to orchestrate a compromise measure by which Arizona and New Mexico would be welcomed into the Union as one large state rather than two separate ones. The proposal was known as jointure, and it gained the support of few people in either territory. Jointure was considered a great compromise in Congress, however. Quay believed that by offering to bring the two territories into the Union as one large state, Beveridge would be forced to end his opposition to statehood.

When Quay issued the jointure compromise, Beveridge was in the middle of a filibuster to prevent a vote on the earlier measure to bring Arizona and New Mexico into the Union as separate states. Although Beveridge was entrenched in his resolve not to compromise on the issue, he also realized that the filibuster could prove a political liability by painting him as intransigent. He also understood that jointure would resolve his central reasons for opposing individual statehood. “Greater Arizona,” as he called the proposed state, would have diminished hispano influence in political matters and all but guarantee a Republican majority there for the foreseeable future.

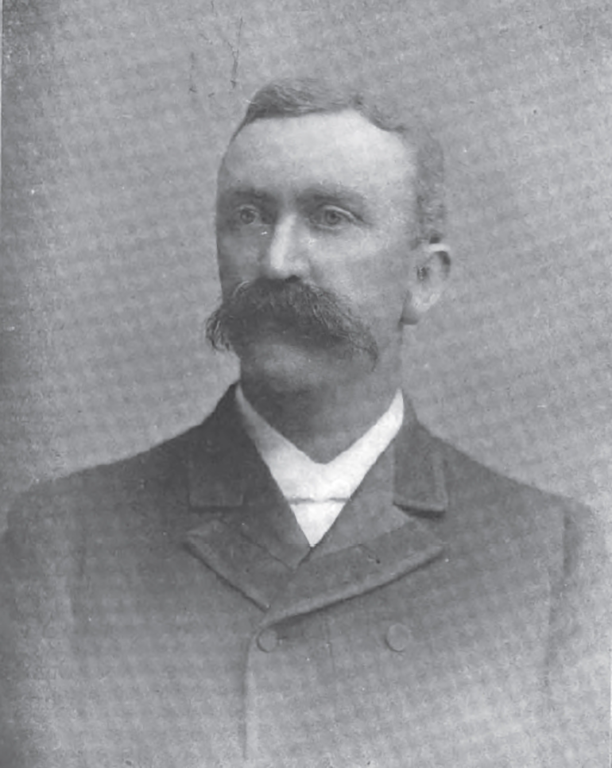

Neale, Walter (1899). “Autobiographies and portraits of the President, Cabinet, Supreme Court, and Fifty-fifth Congress”, Volume 2. Washington D.C.:The Neale Company. p. 532.

For the first time since 1848 it seemed that Congress would approve statehood for Arizona and New Mexico. Quay and his supporters believed that jointure would not be overly problematic for people in the territories because they had been a single entity prior to 1862. Yet Arizona’s Congressional delegate, Democrat Mark Smith, rallied in opposition to the proposal. According to his declaration, residents of Arizona would prefer territorial status for another fifty years to statehood joined with New Mexico.

Smith’s efforts killed the bill in the Senate for the time being as a weary Quay conceded defeat rather than endure the filibuster threatened by Democratic senators. Over the next few years, new bills were introduced and considered in Beveridge’s Committee on Territories, and in 1906 jointure was once again the proposed solution. As a compromise supported by President Theodore Roosevelt and Senate Democrats, the question of jointure was to be put to a vote in each territory. Along with the government initiative and recall, the referendum was a hallmark of Progressive-Era electoral reform. Within the context of the times, support was strong for the idea that jointure go to the voters.

In a clear illustration of his willingness to set Progressive ideals aside for political ends, Beveridge opposed the referendum. In a two-and-a-half hour speech before the Senate, he argued that statehood involved the general welfare of the nation as a whole. For that reason, the desires of the residents of the respective territories were unimportant. What mattered most was that jointure would be best for the nation at large. Still making no secret of his disdain for New Mexicans, Beveridge backed up his arguments with the claim that the territory’s people were “not of the blood and speech that is common to the rest of us.”10 The population of Arizona was too sparse, by his count, to warrant statehood. The only reasonable solution was jointure—no matter the opinions of Arizonans or New Mexicans.

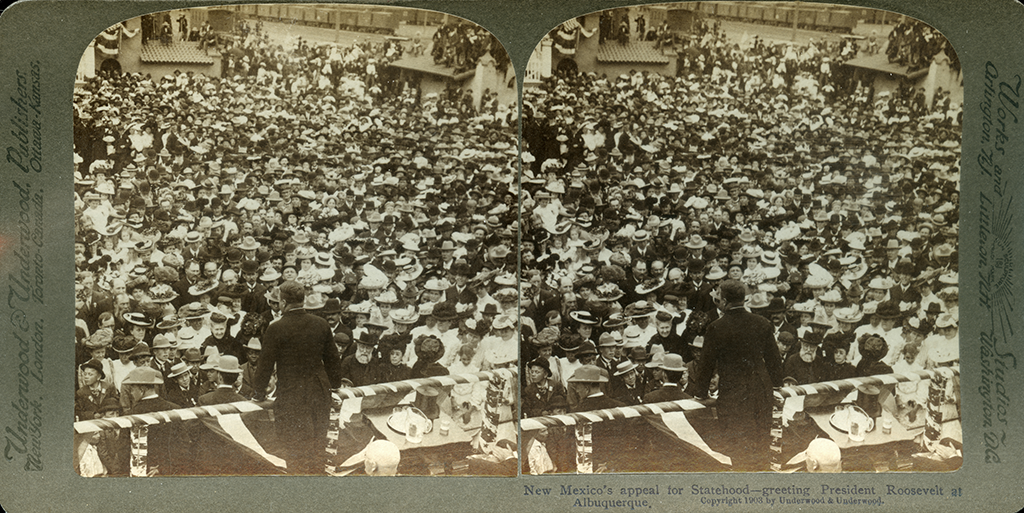

Underwood and Underwood (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 133280.

Beveridge was unable to stop the referendum despite his best efforts, but he used other avenues to ensure a favorable outcome. He persuaded President Roosevelt to replace New Mexico’s governor, Miguel A. Otero, Jr., with someone favorable to jointure. In January 1906, Roosevelt complied when he appointed Herbert J. Hagerman as governor. After only a year in office, Hagerman became entangled in accusations of electoral irregularities and land fraud; Roosevelt then replaced him with George Curry, another ally of jointure. Fraud accusations surfaced throughout the first decade of the twentieth century and they painted New Mexico as a place rife with political corruption and, as such, unfit for statehood.

Despite the continued vocal opposition to the proposal by key territorial figures like Miguel A. Otero and Thomas B. Catron (who typically were opposed to each other), Governor Hagerman, delegate William H. “Bull” Andrews, and Holm O. Bursum united New Mexico’s Republicans in support of the measure. Even L. Bradford Prince, still a vital voice in the territory, decided that joint statehood was better than none.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 002309.

President Theodore Roosevelt also exerted a great deal of influence on the shift in public opinion in New Mexico toward support for jointure. Roosevelt had pledged his aid for statehood to many of the nuevomexicano Rough Riders a decade earlier, and he continued to participate in regular Rough Riders reunions in the territory. Many nuevomexicanos saw him as one of their strongest allies and advocates, so when he publicly argued that jointure was their best option, his opinion carried great weight.

Arizona continued to present the strongest opposition to jointure, based heavily on racist feeling toward the idea of including New Mexico’s hispanos and Pueblos among their ranks. To help turn the tide, President Roosevelt wrote an open letter to Arizonans that was distributed widely in both territories. He asked that those who stood against jointure give it “their sober second thought.” He also emphasized the reality that if they passed this opportunity by, “they will have to wait very many years before the chance again offers itself, and even then it will very probably be only upon the present terms—that is upon the condition of being joined with New Mexico.”11

Although New Mexicans supported jointure in the November 1906 vote with 26,195 in favor and 14,735 against, the measure was soundly defeated in Arizona, 3,141 for and 16,265 against. As Holtby notes, Arizonans believed that a resounding defeat was necessary because Congress might decide to ignore a narrow defeat of jointure. Interestingly, if the votes of both territories were combined, the jointure measure still narrowly failed by a margin of 1,664 votes. Much to the relief of Arizonans, the idea of joint statehood was dead, never again to be revived in Congress.12

William Walton (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 008119.

After so many heated battles on the floor of Congress, in the backrooms of Washington, D.C. and Santa Fe, across the pages of the territorial press, and throughout New Mexico, the actual arrival of statehood in 1912 came as something of an anticlimax. None of the key disputes changed or were definitively resolved. Jointure had been defeated, but it was the waning political influence of Senator Beveridge combined with the campaign promises of new President William Howard Taft that resulted in the Enabling Act that passed Congress in 1910.

On October 3, 1910, a group of 100 delegates from across the territory met in Santa Fe for the purpose of drafting a new state constitution. They were a diverse group with myriad competing interests: seventy-nine Republicans and twenty-one Democrats reflecting the strength of the Grand Old Party in the territory. Regardless of party, one-third were nuevomexicanos and two-thirds Anglo Americans. Reportedly, several delegates kept guns in their desks at the convention, highlighting the extremely tense atmosphere of the negotiations.

Democrat Green Barry Patterson represented Chaves County at the convention and he wielded great power and influence in his sector of the territory. He walked out of the convention when delegate Albert B. Fall (who later became one of the new state’s first senators along with Thomas B. Catron) refused to retract a statement that Patterson found offensive. Additionally, Patterson signed his name to the completed constitution, and then carefully crossed it out in a demonstration of his opposition to the convention’s work.

In many ways, the constitution drafted in 1910 resembled the one penned at the 1889 convention, despite Democrats’ efforts to include Progressive measures, such as initiative, recall, and referendum. Although such measures were not included in the final draft, the constitution did include some vaguely Progressive elements. For example, it allowed women to participate in school-board elections without fully granting them the right to vote. Democrats sought to empower citizens’ role in governance through the constitution. Yet as Holtby has shown, “Republicans, who were in the majority on all the committees, generally opposed such efforts and heeded President Taft’s advice to eschew citizen-driven reforms.”13

On January 21, 1911, New Mexican voters approved the constitution and it was passed on for the approval of Congress and the President. Both took issue with only one passage, Article 19, which made future amendments virtually impossible. A revision titled the Smith-Flood resolution made amendments possible, but still quite difficult. Taft accepted New Mexico’s constitution after the change was made. Arizona’s highly progressive constitution met with more resistance from the conservative Taft. Although territorial officials there altered the document to appease the President, the state’s residents amended their constitution within a year to allow for provisions such as female suffrage, referendum, recall, anti-lobbying clauses, and anti-child labor measures.

Just less than a year after the territorial vote, on January 6, 1912, President Taft was joined by thirteen guests from New Mexico to formally acknowledge statehood. With no fanfare or ceremony, Taft signed the document that welcomed New Mexico into the Union. After signing, he uttered only two sentences: “Well, it is all over, I am glad to give you life. I hope you will be healthy.”14

Harris and Ewing (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 089760.

What Taft said is noteworthy, not only for its patronizing tone but also for what his comments omitted. Even today, statehood is often heralded as the culminating event of New Mexico’s past. That viewpoint, however, negates the centuries-long histories of the peoples who have inhabited the area and built their lives in New Mexico. Celebratory photographs that show the thirteen citizens invited to the White House on that cold January day only depict Anglo-Americans, and of that group only three women were present.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

As Holtby emphasizes, missing are representatives of four groups enumerated in the 1910 Census: nuevomexicanos (155,155), Native Americans (20,575), African Americans (1,628), and Asian Americans (504). Many of the Asian residents of New Mexico had migrated stealthily across the U.S.-Mexico border because the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act expressly forbade their entry into the nation. Additionally, the group of invitees does not reflect the gender composition of New Mexico at the time: of those age fourteen and older, 114,295 were men and 92,257 were women.15

Holtby’s demographic analysis is important because it reminds us that, despite Taft’s wish that the new state “be healthy,” it remained more diverse and troubled than national debates suggested. Despite the benefits of statehood, including the end of second-class citizenship for New Mexicans, it was not a cure-all for ongoing issues. The new state had to confront difficult problems, such as endemic poverty and illiteracy. Corruption in politics continued and outside corporations still exploited New Mexico’s natural resources at the expense of local residents.