The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 14: World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II

- Manhattan Project

- Site Y

- Testing the Bomb

- Impact on Local Communities

- References & Further Reading

After months of research, development, and localized testing of hypotheses, Oppenheimer and other physicists realized that they would need to test the bomb once it had been completed. They were uncertain whether their design would detonate, and they did not fully understand what the consequences of a nuclear explosion would be.

Two different types of atomic weapons were created at Los Alamos; one used uranium and the other used plutonium. The scientists were most concerned about the detonation of the plutonium bomb because the “gun method” that they used with the uranium device would not work with plutonium. As an alternative, they developed an implosion method in which the plutonium was to be surrounded with explosives (TNT); the explosion of the TNT would theoretically compress the plutonium and ignite the nuclear chain reaction. Although they were certain the gun method would work with uranium, they were less sure about the implosion method.

Between May and November 1944 debates ensued throughout Los Alamos about whether to conduct a live test of the plutonium bomb. Oppenheimer and George B. Kistiakowsky, an explosives expert at Harvard, argued that the test was necessary but General Groves opposed the idea. His main concern was that if the test failed to produce a nuclear explosion, plutonium would be strewn across the desert.

Facilities at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington, had been established to produce the fissionable uranium isotope, U-235, and plutonium for the work at Los Alamos. U-235 is rare, however, and in 1940 scientists estimated that they would need twelve million years to extract a pound of the isotope from naturally occurring uranium. As an alternative, plutonium was created by bombarding uranium-238 with neutrons through a complex process.

The creation of plutonium, however, was not much quicker than the creation of U-235. Following the war, General Groves spoke of the teams at Oak Ridge and Hanford in the highest terms due to their ability to develop new techniques for the extraction of U-235 and the generation of plutonium. The result was the production of several pounds of each in just a few years during the war.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Groves’ opposition to the test was primarily due to his fear of losing the fissionable material, upon which the project relied, with nothing to show for the effort. In the end, Oppenheimer convinced the general to approve a field test by proposing the construction of an enormous, 214-ton tank that the team called “Jumbo” to contain the plutonium if the blast failed. If the test was successful, on the other hand, Jumbo would be incinerated.

In November 1944 Oppenheimer’s team chose a desert section of the Alamogordo Bombing Range, today the White Sands Missile Range, as the site for the test. Located in southern New Mexico’s Jornada del Muerto, the site is often associated with the town of Alamogordo which is about sixty miles distant. Socorro was the nearest population center of consequence, about thirty miles to the north. The land itself had belonged to the state of New Mexico and been leased to ranchers for grazing. When the United States entered the war, the military took control of the area.

It seems that Oppenheimer named the site Trinity based on his study of the Vedic texts, although historians continue to debate exactly how the site was named. Historian Marjorie Bell Chambers was the first to attribute the name to Oppenheimer’s study of Hindu belief.16 As historian Ferenc Szasz later explained, “the Hindu concept of Trinity consists of Brahma, the Creator; Vishnu, the Preserver; and Shiva, the Destroyer. For Hindus, whatever exists in the universe is never destroyed. It is simply transformed.”17 Given that Oppenheimer’s team produced the most destructive weapon yet known to humankind, the idea that nothing is truly destroyed might have offered some comfort.

Once the location was secured, a number of theoretical concerns remained. Among the most troubling was that the physicists were not sure whether or not an atomic explosion would ignite the earth’s atmosphere. As construction of the Trinity site proceeded in early 1945, the question was nothing new. As early as the summer of 1942 Edward Teller’s calculations suggested that the bomb could create enough heat to cause the atmosphere to flare. The result would be the eradication of all life on earth.

Oppenheimer was deeply troubled by Teller’s findings, and he interrupted Arthur H. Compton, head of the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, for a second opinion while he was vacationing with his family in Michigan. The pair conversed for long hours on the banks of Oswego Lake. Ultimately, Compton concluded that if calculations “showed that the chances of igniting the atmosphere were more than approximately three in one million . . . he would not proceed with the Manhattan Project.”18

Back in Los Alamos, several different teams of scientists examined the question over the course of 1943 and 1944. Teller revised his initial figures to account for the presence of cooler air that would occur near the explosion itself, but as late as the fall of 1944 the question had yet to be settled to anyone’s satisfaction. Ultimately, Hans Bethe, head of the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos, calculated that the Trinity test explosion would not ignite the atmosphere. His figures seemed to account for all variables, and, as Kenneth Bainbridge recalled, “We all put our faith in Bethe.”19 An added comfort was that Teller’s revised calculations jibed with those of Bethe.

Several other questions were never fully resolved as the Los Alamos team prepared for the Trinity test. They were not completely sure whether or not the blast would set off earthquakes, although their calculations suggested that the probability of tremors was low. Additionally, they did not fully comprehend the nature of nuclear fallout until years after the Trinity test and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In that regard, the weather—specifically the winds—would be the key to ensuring that the fallout remained relatively contained at the site. Among the ideal weather conditions for the test were visibility greater than forty-five miles, humidity less than eighty-five percent, stable temperature lapse rate, little to no atmospheric inversion, and light winds to the northeast. With winds to the northeast, fallout would travel over the most sparsely populated ranch lands and avoid populated areas like Socorro, Alamogordo, Las Cruces, or El Paso. During the summer months, thunderstorms would be the major weather concern.

Jack Hubbard served as chief meteorologist for the Trinity test. His job was perhaps one of the most stressful. Given the paucity of weather records for the Jornada del Muerto, his task of predicting when the ideal conditions would occur was quite difficult. He successfully forecasted the date of May 7, 1945, for the “100 Ton Shot,” a preliminary test detonation of TNT to help calibrate the instruments at the Trinity site. In June, he made a long-range forecast for the summer that indicated July 18-21 as the best weather window. July 12-14 would be the second best chance for ideal conditions.

The team never addressed the issue that if they opted for Hubbard’s first choice, his second would have already passed. International politics intervened following Germany’s surrender in May of 1945. President Roosevelt had died on April 12, and his vice president, Harry S. Truman became the leader of the United States. Truman had been largely kept in the dark about the Manhattan Project and he was quickly debriefed about its progress and status not long after taking the oath of office.

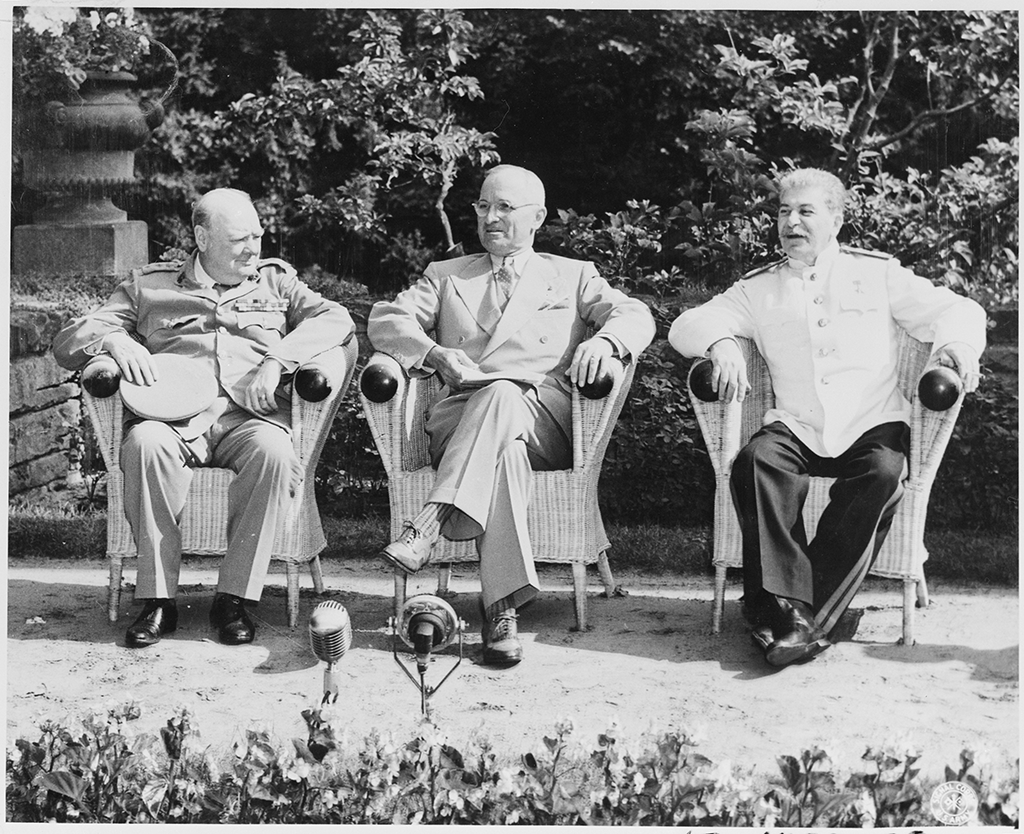

Upon learning of the project, Truman pushed General Groves to hold the test to correspond with his conference at Potsdam, a suburb of Berlin, with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin. He believed that news of a successful atomic test would provide the upper hand in negotiations between the “Big Three” regarding the shape of the postwar world. Under pressure from above, Groves set July 16 as the date for the test.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Hubbard was tasked with watching the weather in the hours leading up to the test, and he was to make the call of whether or not to go ahead. On the evening of July 15 he predicted light, variable west-to-southwest winds for the next morning. Violent thunderstorms developed in the area overnight. At 2 a.m., Hubbard advised the team to postpone the test by one hour; he predicted that, by that time, the winds would change and the storms would dissipate.

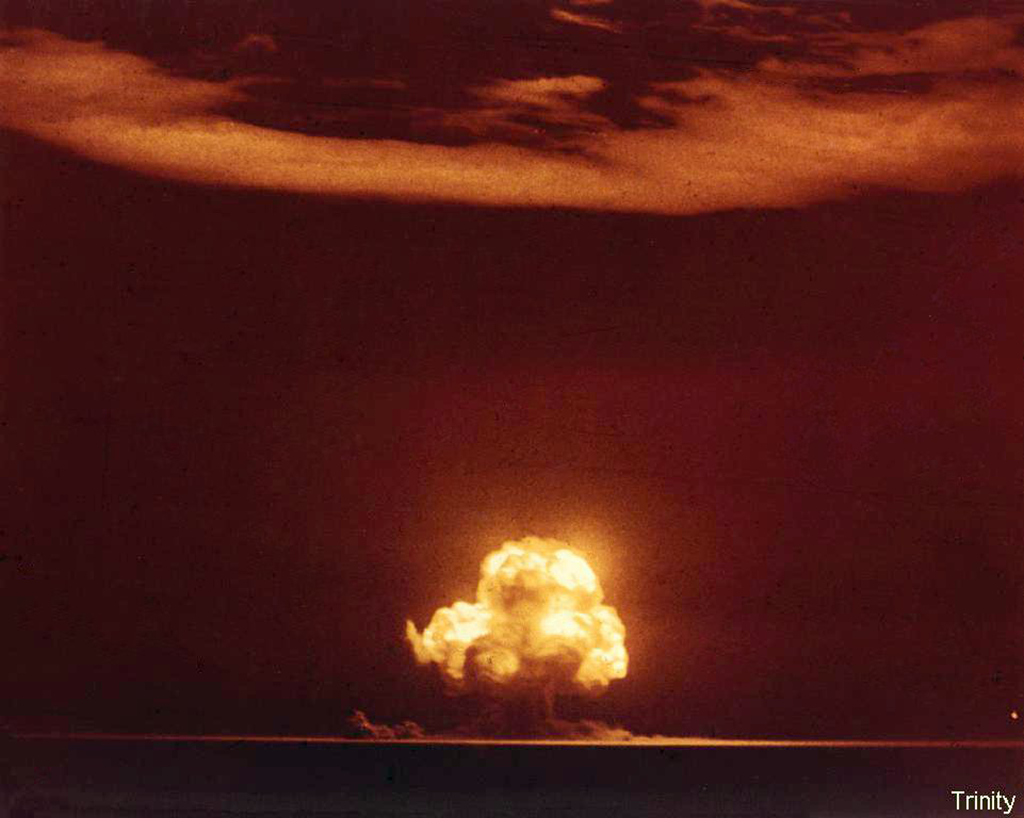

When the test occurred at 5:30 on the morning of July 16, 1945, almost none of the ideal weather conditions were met—except the winds. They had changed direction as Hubbard had predicted. The blast exceeded all expectations. By several reports, it lit up the entire area like the sun. Heat at its core was comparable to that of the center of the sun, and the fireball created a half-mile crater. People in at least three states saw the light from the explosion, which projected a mushroom cloud 38,000 feet into the atmosphere. Every living thing was destroyed within a mile radius.

Photograph by Jack Aeby, courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

Members of the Los Alamos team witnessed the blast from several vantage points around the site, all at a safe distance from the bomb. Enrico Fermi experienced the explosion from 10,000 feet away. Just before the bomb ignited, he tore up a piece of paper. Immediately after the explosion, he let go of the papers to see how far the blast wave carried them. Based on his calculations, the bomb’s force was equal to about 10,000 tons of TNT.

Forest Ranger Ray Smith was on duty near Lookout Mountain, northwest of Silver City when the test occurred. He reported feeling an earthquake, as did residents of the small town of Carrizozo. Santa Fe Railroad engineer Ed Lane was on a train near Belen that morning, and he later commented that “he had a front seat for the greatest fireworks show he had ever witnessed.”20

According to many New Mexicans in the southern half of the state, the sun rose and then went down again at 5:30 on the morning of July 16. Reportedly, Georgia Green, a blind woman living near Socorro, even knew that something major had occurred. The bomb produced more than visual effects.

The Trinity test intensified General Groves’ efforts to maintain secrecy because so many people in the region knew that something of a great magnitude had occurred—even if they did not understand what had happened or who was responsible. As had been the case throughout the work of the Manhattan Project, Groves even instructed the scientists to keep the truth from their wives.

The official press release explained that “a remotely located ammunition magazine containing a considerable amount of high explosives and pyrotechnics” had been accidentally set off. No one was injured, no property damaged. People removed from the Trinity site by distance, such as the inhabitants of Albuquerque, accepted the official explanation. Locals nearer the blast were more skeptical, however.

Alamogordo resident Beatrice McKinley, for example, reported, “Everybody knew something had happened. The stories they told were very clumsy.” Indeed the Alamogordo News printed both the official press release as well as accounts from locals that “some experimentation was going on in explosives which required an isolated terrain such as the explosion occurred on.”21 Similar reactions characterized the responses of Lincoln and Doña Ana County residents. New Mexicans understood well that the federal government had used their home state as a proving ground for an awesome new weapon.

Although President Truman had insisted upon the July 16 test date in order to gain bargaining position at the Potsdam Conference, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin was not surprised. Information from Klaus Fuchs through Soviet informants had not yet apprised him of the magnitude of the weapon’s power, however. A Soviet nuclear program had been in motion since the 1930s, and it intensified in 1942 when its primary scientists alerted Stalin that publications on nuclear developments in the United States had ceased.

In a brief and awkward exchange on July 24, Truman mentioned in passing to Stalin that U.S. scientists had successfully tested a new and powerful weapon. Stalin briefly responded with approval and he urged President Truman to use the atomic weapon against the Japanese. Truman believed that his Soviet counterpart had missed the gravity of his remark.

Following the Trinity field test, the central question that was debated among high-level military officials and U.S. policymakers was whether or not to use the atomic bomb. Indeed, the ongoing debates about atomic weapons and energy have gravitated back to that question in one way or another ever since 1945.

Many different lines of reasoning for and against the use of atomic weapons have been proffered since the close of World War II. The cliché that “hindsight is twenty-twenty” seems to fit subsequent debates about nuclear weapons. Those involved in the conversation at the time had no such luxury. Some argued that the U.S. military should not use the atomic bomb because to do so would open Pandora’s Box—all other nations would race to create the same destructive technology.

Other voices clamored for the use of the weapon. Some argued that the use of the atomic bomb would not only end the war against Japan, it would also intimidate Stalin and the Soviet Union. The wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviets was strained at best; the end of the war led to increased polarization as Truman and Stalin each made opposition to the other nation a specific, nationalist goal.

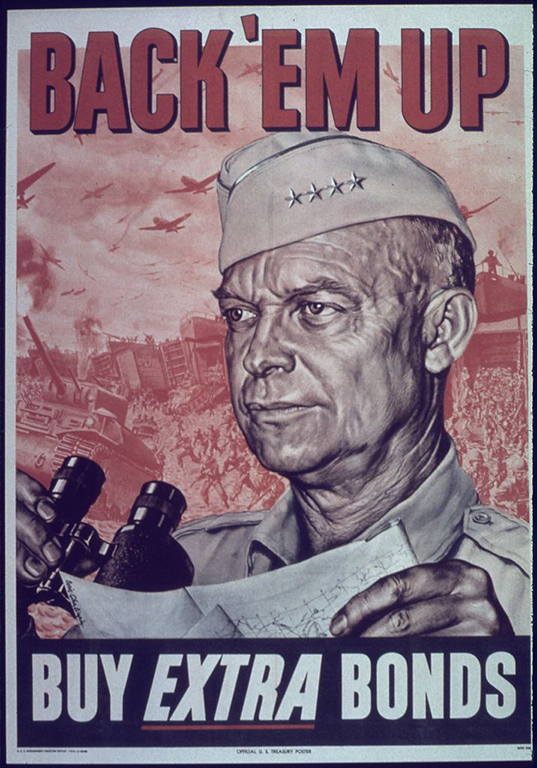

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

President Truman also felt pressure from the American electorate to end the war as soon as possible in order to save the lives of U.S. servicemen and women. One of the other lines of reasoning in support of using the bomb centered on the idea that to do so would preserve the lives of American soldiers. Revisionist historians after 1945 painted Truman as something of a villain regarding the use of atomic weapons at the close of the war. By taking that action, they asserted, he appeased those who wanted to project strength to the Soviets and he simultaneously used the lives of U.S. servicemen and women for political ends.

A significant contingent of Americans and U.S. military leaders opposed the use of atomic weapons based on the idea that nuclear bombs were unnecessary. Among those who voiced this opinion were Dwight D. Eisenhower, top military official in the European theater. Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in the Pacific theater, and General George C. Marshall, overall commander of the U.S. military effort in World War II, shared this view. Eisenhower argued that Japan was already on the verge of defeat whether or not the bomb was used. Nimitz argued that the U.S. military did not need to open Pandora’s Box through the use of nuclear weapons. And, after the fact, Marshall publicly declared that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki only shortened the war by a few months at most.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Debates over the decision to use atomic weapons at the close of World War II will certainly continue in historical and public forums. In The Day the Sun Rose Twice, historian Ferenc Szasz placed Truman’s decision in its political and social context. He emphasized the enormous pressure placed on the president to save U.S. lives and end the war at the earliest date possible. Additionally, scientists, politicians, and military officials did not fully recognize the potential ramifications of the use of atomic weapons in 1945. Teams from Los Alamos and certain U.S. and European universities traveled to Trinity, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, to study the effects of the devastating explosions and fallout.

As debates ensued in U.S. political and military circles about whether or not to use nuclear weapons in Japan, the arguments were overshadowed by the reality that the nation had poured a massive level of resources and funding into the Manhattan Project. Szasz argues for a middle-ground interpretation of events based on “the simple question of momentum of the Manhattan Project.” Oppenheimer once remarked that “the decision [to drop the bombs] was implicit in the project.”22 Several of the physicists involved in the project were deeply conflicted as they witnessed the Trinity test because they knew that the intention had always been to use atomic bombs in combat.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

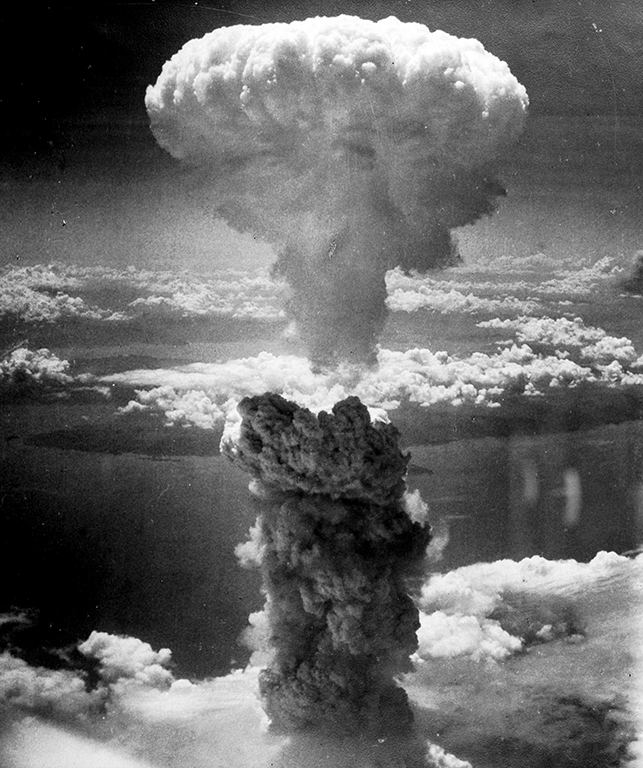

The historical context involving the Manhattan Project’s momentum is important for understanding the use of atomic weaponry in World War II, but that context does not minimize the destruction wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Only three weeks after the Trinity test, on August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, a city of about 320,000 people at the time. Between 70,000 and 80,000 were killed instantly and another 100,000 or so died over the next few years due to burns and radioactive fallout.

Three days later, the Bockstar dropped another nuclear bomb on the city of Nagasaki. With an estimated population of just over 260,000 people, casualties there were even more extensive than had been the case at Hiroshima. In central Hiroshima, the mortality rate per square mile was 15,000; in Nagasaki 20,000. By comparison, the firebombing of Tokyo in March of 1945 caused a casualty rate of 5,300 people per square mile.23 The initial number of casualties in Nagasaki numbered about 100,000.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Many survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki have shared their accounts of the experience of living through an atomic attack. Their accounts detail the intense human suffering caused by the blasts. Among publicly available accounts are these:

Photographer Yosuke Yamahata was present in Nagasaki during the bombing, and he took a series of photographs to document the destruction and loss of life. An online gallery of his work, along with brief commentary, is located at Nagasaki Journey. As Yamahata poignantly reminds us:

Human memory has a tendency to slip, and critical judgment to fade, with the years and with changes in lifestyle and circumstance. But the camera, just as it seized the grim realities of that time, brings the stark facts . . . before our eyes without the need for the slightest embellishment. Today, with the remarkable recovery made by both Nagasaki and Hiroshima, it may be difficult to recall the past, but these photographs will continue to provide us with an unwavering testimony to the realities of that time.24

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Whether intended or not, the Manhattan Project marked a major turning point in world history. Human beings had constructed a weapon that was powerful enough to potentially destroy all of humankind, if used in combat without restraint. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced the surrender of Japan on August 10, 1945. As famed television journalist Edward R. Murrow remarked following the end of the war, “Seldom if ever has a war ended leaving the victors with such a sense of uncertainty and fear, with such a realization that the future is obscure and that survival is not assured.”25

Within a few years the Cold War ignited an arms race that pitted the United States and its allies against the Soviet Union and its allies. Even more powerful weapons with wider range were created, such as the hydrogen bomb developed under the direction of Edward Teller and ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads. Historian Jon Hunner reminds us that New Mexico, and specifically Los Alamos, “was a nucleus of this atomic future.”26

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory