Timeline tasks

There are many steps to producing a textbook, and each of those steps involve multiple responsibilities. As you record these on your timeline, calculate how long each will take — and then add some additional time as a buffer.

Research

Track all references carefully as would be done for any academic work. If you are using openly-licensed text, images, or other resources, be mindful of the legal requirements for the license. (Research.)

Gather or create resources

Resources may include photos, illustrations, graphs, tables, figures, videos, audio files, or spreadsheets. Remember, if you’re using someone else’s work, it must be openly-licensed or in the public domain. If a resource is copyrighted and all rights are reserved, you may provide a link to it. However, linking should only be used as a last resort when an openly-licensed resource cannot be located. (Resources: Only the Open.)

Write the book outline

This includes chapters, chapter sections, front and back matter, learning objectives, exercises, key terms and takeaways, and the glossary. Outline how chapters and chapter sections will be laid out. (Textbook Outline.)

Find supplemental resources

Not all textbook authors or publishers create ancillary resources, such as test banks, for their books. However, many instructors and students find them helpful, and textbooks with ancillary resources are often highly adopted. Determine what your textbook will need in order to be most effective.

Plan each chapter

During the book-outline phase, determine the structure for each chapter in addition to the research and resources required to write it. Record these in your timeline beside the designated author. Use this information to calculate how long each chapter will take to complete. Remember to build in extra time for the beginning phase of the project, as this is when you and your team are learning to work together and with the textbook, and for any unanticipated delays. While working with many authors is a good way to incorporate expertise and multiple viewpoints, it will take extra time as you or your project manager communicate with the team and manage their work. (Textbook Outline, Contributing Authors, and Identify Support.)

Peer review

Schedule time for the peer review of your textbook by subject-matter experts. (Peer Review.)

Copy edit

Have the book copy edited. (How to Copy Edit.)

Proofread

Have the book proofread. (How to Proofread.)

Prepare for publication

Conduct a final check of your book and contact Distance Learning to place in MyText. (The Final Check )

Promote

Launch and communicate about your new book. (Communications.)

For more information, see the Authoring Open Textbooks chapter on Developing a Timeline[New Tab]. Project Charter and Timeline by Lauri Aesoph is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. https://opentextbc.ca/selfpublishguide/chapter/project-timeline/

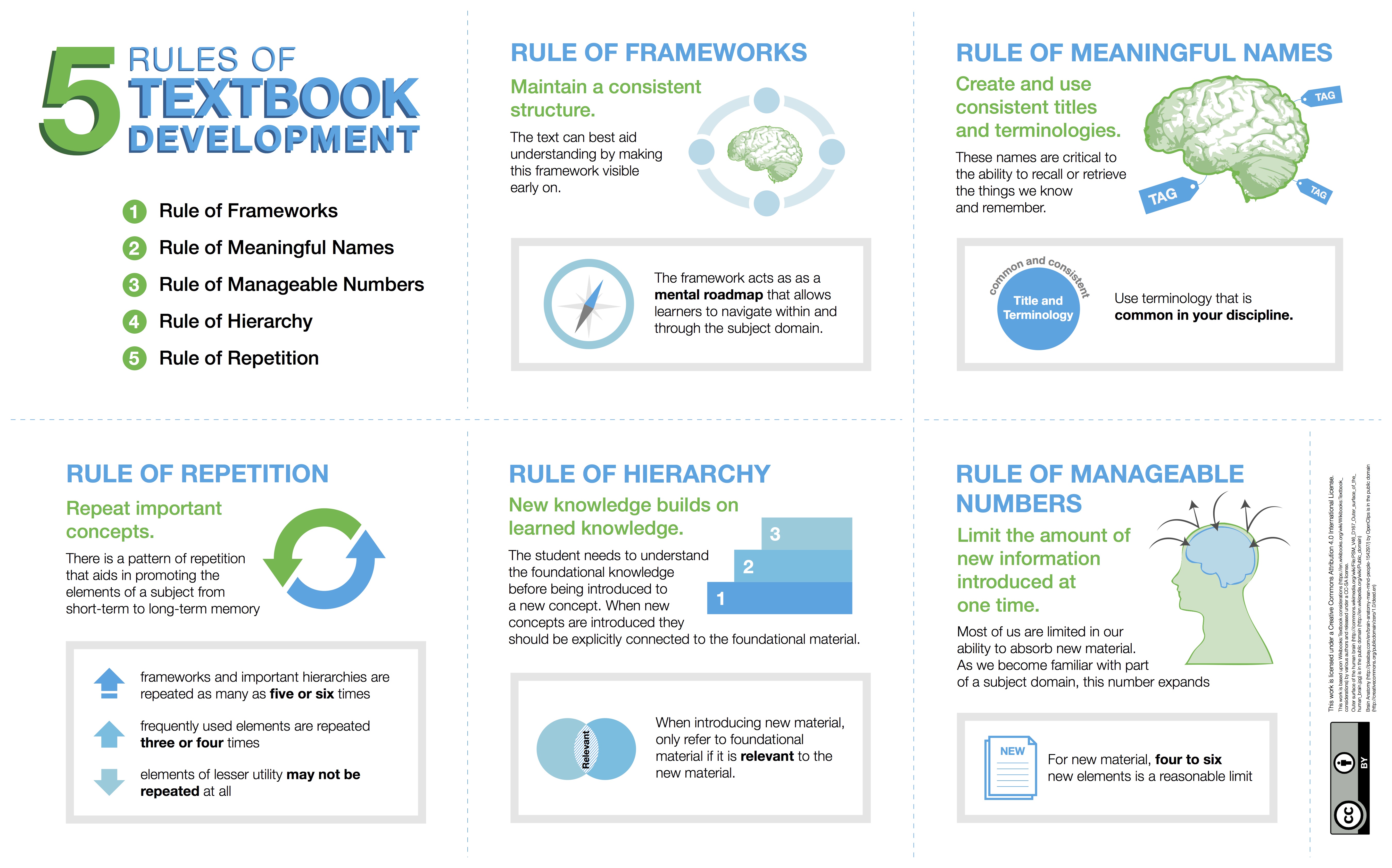

Five Rules of Textbook Development

-

Rule of frameworks

Memory and understanding are promoted by the use of a structure that mimics the structures we all use within our minds to store information. Before we can use or master a subject, we have to have a mental road map that allows us to navigate within and through the subject domain. The text can best aid understanding by making this framework visible early on within each section or topic. The extent to which the student understands that they are using a framework, and knows what that framework is, is important as they internalize and make use of the material presented.

-

Rule of meaningful names

Everything we know is tagged with an index or a title. These indices are critical to the ability to recall or retrieve the things we know and remember. Each concept, process, technique or fact presented should aid the student to assign a meaningful name for it in their own mental organization of the material. To be most useful, these names shouldn’t have to be relearned at higher levels of study. The names assigned by the text should be useful in that they support some future activities: communication with other practitioners, reference within the text to earlier mastered material, and conformity to the framework used for the subject. Each unique element of the subject domain should have a unique name, and each name should be used for only one element.

-

Rule of manageable numbers

When we learn from an outline, an illustration, or an example, most of us are limited in our ability to absorb new material. As we become familiar with part of a subject domain this number expands, but for new material four to six new elements is a reasonable limit. If a chapter outline contains twelve items, the student will have forgotten the outline before getting to the last item. When a text fails to support this rule, it requires even a diligent student to needlessly repeat material.

-

Rule of hierarchy

Our mental frameworks are hierarchical. Learning is aided by using the student’s ability to couple or link new material with that already mastered. When presenting new domains for hierarchical understanding, the rules for meaningful names and manageable numbers have increased importance and more limited application. A maximum of three levels of hierarchy should be presented at one time. The root should be already mastered, the current element under consideration clearly examined, and lower levels outlined only to the extent that they help the student understand the scope or importance of the current element. This area is supplemented by two more rules within this rule: those of Connectivity and Cohesion. Connectivity requires consideration of what the student likely knows at this point. The more already mastered elements that one can connect with a new element, the easier it is to retain. Cohesion requires that the characteristics of new elements as they are presented be tightly coupled.

-

Rule of repetition

Most people learn by repetition, and only a few with native genius can achieve mastery without it. There is a pattern of repetition that aids in promoting the elements of a subject from short-term to long-term memory. Implementations of this rule may mean that frameworks and important hierarchies are repeated as many as five or six times, while frequently used elements are repeated three or four times, and elements of lesser utility may not be repeated at all. The first repetition should normally occur within a day of first presentation, followed by a gradually decreasing frequency. Exercises and review sections are ideally contributing to a designed repetition pattern.

Attributions: The content in the above material comes from Wikibooks:Textbook considerations and is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 Licence. “Wikibooks:Textbooks considerations,” Wikibooks, https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Wikibooks:Textbook_considerations (accessed January 24, 2018).