Part 4: Chapter 25

After discussing general strategies for analysis and applying these strategies to specific examples in class, students often ask questions like the following:

“This has all been well and good, but when are we going to actually learn how to write?”

A student’s confusion most likely emerges from how (s)he was taught in the past. In most school assignments, writing does not require thinking so much as the stuffing of obvious considerations or memorized material into formulated structures, like a five-paragraph essay or a short answer exam. However, in less restrictive writing situations the specific way we articulate our analysis emerges from what we think of it, and thus our best writing comes through our most careful considerations. While there is no easy formula for organizing an analytical essay, successful analytical writers use general strategies we can examine, though the specific way you enact these strategies will depend on the ideas that you have already discovered.

Focusing Your Analysis

After examining your subject thoroughly and reading what others have written about it, you might have so much to write that you will not be able to cover your perspective adequately without turning your essay into a book. In such a case you have two options: briefly cover all the aspects of your subject or focus on a few key elements. If you take the first option, then your essay may seem too general or too disjointed. A good maxim to keep in mind is that it is better to say a lot about a little rather than a little about a lot; when writers try to cover too many ideas, they often end up reiterating the obvious as opposed to coming up with new insights. The second option leads to more intriguing perspectives because it focuses your gaze on the most relevant parts of your subject, allowing you to discern shades of meaning that others might have missed.

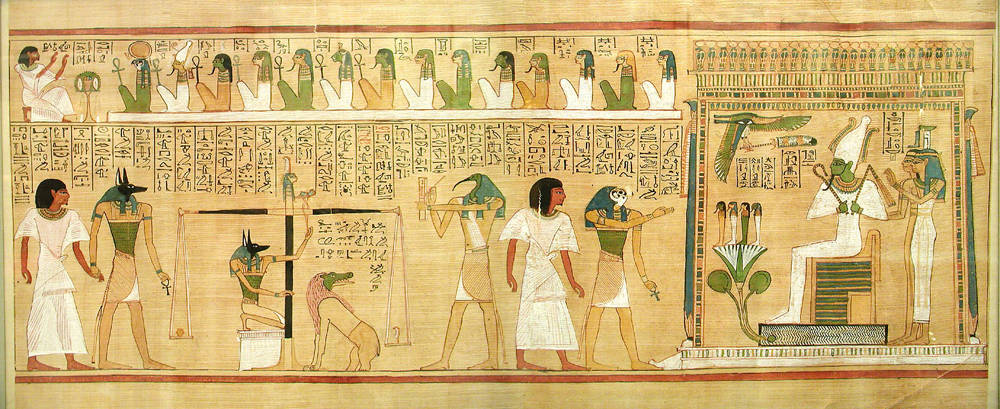

To achieve a stronger focus, you should first look again at your main perspective or working thesis to see if you can limit its scope. Consider whether you can concentrate on an important aspect of your subject. For instance, if you were writing an essay for an Anthropology class on Ancient Egyptian rituals, look over your drafts to see which particular features keep coming up. You might limit your essay to how they buried their dead, or, better, how they buried their Pharaohs, or, even better, how the legend of the God Osiris influenced the burial of the Pharaohs.

Next, see if you can delineate your perspective on the subject more clearly, clarifying your argument or the issue you wish to explore. This practice will help you move from a working thesis, such as

“Rituals played an important function in Ancient Egyptian society,”

to a strong thesis:

“Because it provided hope for an afterlife, the legend of Osiris offered both the inspiration and methodology for the burial of the Pharaohs.”

Once you have focused the scope of your thesis, revise your essay to reflect it. This practice will require you to engage in what is usually the most painful part of the writing process—cutting. If something does not fit in with your perspective, it has to go, no matter how brilliantly considered or eloquently stated. But do not throw away the parts you cut. You never know when you might find a use for them again. Just because a particular section does not fit well with the focus of one essay does not mean that you won’t be able to use it in another essay down the road. Create a second document where you can paste all the text you cut from your draft document. This allows you to go back and review the text as you continue to work on your writing.

Expanding

After cutting your essay down to the essential ideas, look it over again to make sure that you have explored each idea adequately. At this point it might help to ask yourself the following questions:

-

Do your assertions clearly reveal your perspectives on the subject?

-

Do you provide the specific examples that inspired these assertions?

-

Do you explain how you derived your assertions from a careful reading of these examples?

-

Do you explore the significance of these assertions as they relate to personal and broader concerns?

If any long sections seem lacking in any of these areas, you might explore them further by taking time out from your more formal writing to play with one of the heuristics recommended in various sections throughout this book (freewriting, brainstorming, clustering, metaphor extension, issue dialogue, and the Pentad). You can then incorporate the best ideas you discover into your essay to make each section seem more thoughtful and more thorough.

Now that we’ve looked at each of these areas of analysis more carefully, let’s go back to the main example from Chapter 19, the passage from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. At the end, there is an example of a paragraph that includes each aspect of analysis, but while these aspects are all present, none of them are developed fully enough for even a brief essay on the passage. Beginning with the examples, the paragraph makes brief reference to the “baseless fabric of the vision of cloud capped towers” and to the “great globe itself,” pointing out how these phrases refer to items associated with Shakespeare’s theater as well as the world outside of it. But we could also discuss other terms and phrases that appear in the quote. For instance, we could discuss the implications of the word revels in the first line. These days we probably wouldn’t say revels but instead celebrations, or, less formally, partying, but the word clearly refers back to the play within the play that comes to an abrupt end. In this context, the implication is that above all, the purpose of plays should be for enjoyment, a sentiment reflected in the epilogue when Prospero speaks directly to the audience:

“gentle breath of yours my sails/Must fill, or else my project fails, Which was to please.”

As we further consider the implications, we might be reminded of past teachers who made reading Shakespeare feel less like a celebration and more like a task, as something to be respected but not enjoyed. We could then explain how the word revels serves as a reminder to enjoy his plays, and not because they are “good for us” like a nasty tasting vitamin pill, but because if we’re willing to take the effort to understand the language, the plays become deeply entertaining. Looking back over the passage and seeing how plays are equated to our lives outside the theater leads to an even more significant insight. We should try to see life as a celebration, as something to be enjoyed before we too disappear into “thin air.” In discussing the significance of this, we wouldn’t simply wrap it up in a cliché like “I intend to live only for today,” but explore more responsible ways we can balance fulfilling our obligations with enjoying the moments that make up our lives.

Now we can go back and expand the main assertion.

Instead of simply writing, In The Tempest, Shakespeare connects plays, lives, and dreams by showing that while each contains an illusion of permanence, they’re all only temporary,

we might also add,

But this does not mean that we should waste the time we have on earth or in the theater lamenting that it will all soon be over. Instead we should celebrate, in a responsible manner, our remaining moments.

And because all of these insights came about from examining the implications of only one word, revels, the essay will continue to expand as we consider more details of the passage and consult related research. Eventually, however, we will need to stop expanding our analysis and consider how to present it more deliberately.