The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 14: World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II

- Manhattan Project

- Site Y

- Testing the Bomb

- Impact on Local Communities

- References & Further Reading

Although historians and others have debated the overall impact of the New Deal on the U.S. economy, nearly all agree that it did not bring an end to the Great Depression. American involvement in World War II brought an unprecedented level of spending and technological development that finally pulled the nation out of the depression.

New Mexico’s economy followed the national trend. New Deal programs alleviated families’ immediate suffering but they did not rejuvenate the economy to the point that it was able to function without subsidies. The New Deal initiated a process of increasing federal intervention in New Mexico and throughout the Western United States. During World War II, the federal presence in the West shifted from economic relief to the fortification of the military-industrial complex.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

New Mexico, like many places in the American West, boasted warm seasonal temperatures and an abundance of public land. The federal government located new Air Force Bases, including Kirtland Air Force Base and Cannon Air Force Base, as well as proving grounds, like the Alamogordo Bombing Range, in the state. As had been the case in U.S. war efforts since the Civil War, nuevomexicanos and Native Americans supported the war effort on the homefront and in combat roles throughout Europe and the South Pacific.

The war effort touched New Mexico in many different ways. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps based on the unfounded suspicion that they supported the Japanese war effort. In all, about 112,000 people of Japanese descent were interned; nearly two-thirds were Nisei, or second-generation Americans, and the other one-third were Issei, or first-generation Americans. Nisei had been born in the United States and enjoyed American citizenship.

Many of those interned reported a feeling of complete betrayal and despair when “E-day,” or evacuation day, arrived. Families were forced to sell their homes, possessions, and businesses for pennies on the dollar. They were loaded onto busses and transported to makeshift facilities, which included converted animal stalls, before receiving an assignment to a specific internment camp, most of which were located in remote locations around the Western United States.

In recent years, historians who study the violation of Japanese Americans’ civil liberties have scrutinized the language used to describe their imprisonment. Government officials used terms like “internment” and “evacuation” to suggest the legality of the action and to imply that the “relocation” of Japanese Americans was for their own good—to protect their safety. Many scholars now prefer to use the term “imprisonment” to emphasize the injustice of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Not until 1983 did a Congressional Committee recognize that the mass removal of Japanese Americans from their homes was not a “military necessity,” as had been argued at the time. Instead, the committee attributed the imprisonment to “race war, mass hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”9 For most survivors of internment, however, federal attempts to recuperate their personal losses were too little, too late.

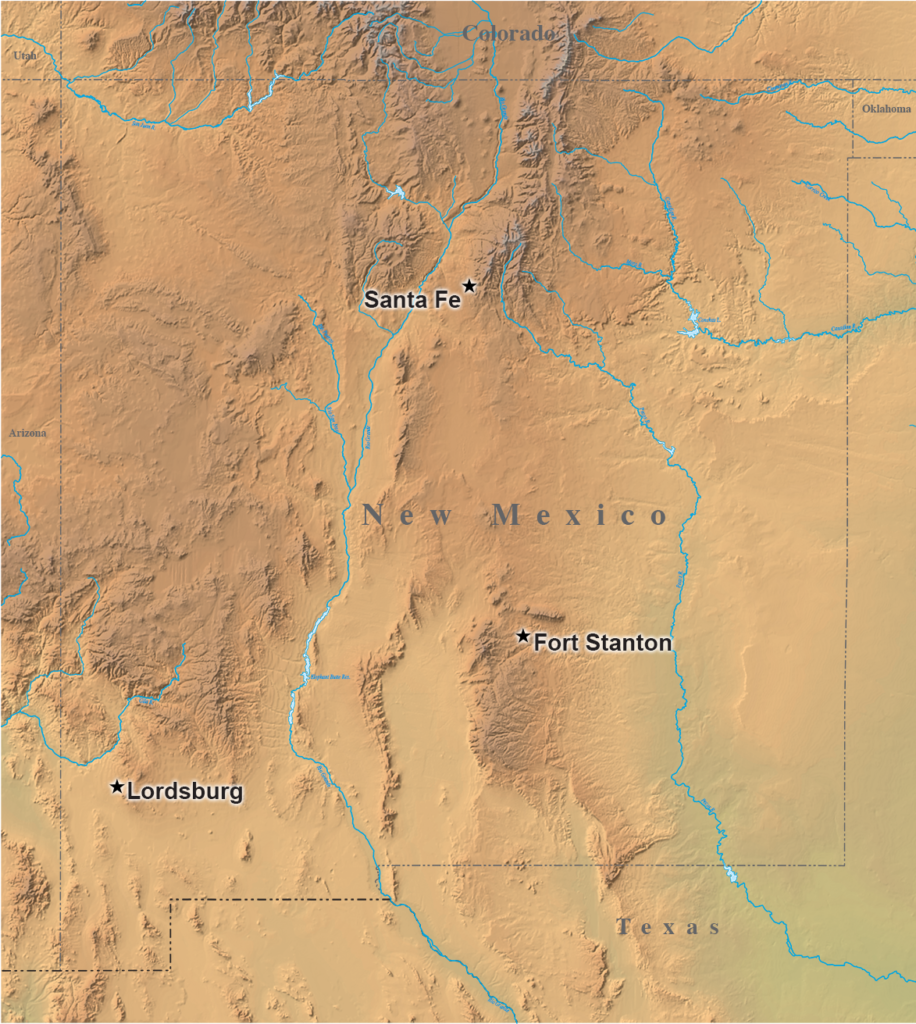

The injustice of Japanese American imprisonment has become public knowledge since the hearings of the early 1980s. Less well known were the internment facilities located near Santa Fe and Lordsburg, in the southwestern corner of the state. Italians and Germans suspected of disloyalty to the United States were imprisoned at the New Mexico facilities, along with Japanese American prisoners. At the Santa Fe camp, 4,555 men of Japanese heritage were imprisoned between March 1942 and April 1946. Far fewer Japanese Americans were sent to the Lordsburg facility, which primarily functioned as a camp for prisoners of war.

Located on a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp, 826 Japanese American prisoners entered the Santa Fe facility in March 14, 1942. Of that number, 303 were determined to be “undesirable alien enemies” following a series of hearings between March and September. The others were allowed to join their families in internment camps in other areas of the Southwest. The camps in New Mexico, then, were reserved for those who the federal government deemed to be a direct threat to the security of the United States. Other Japanese American prisoners later entered the camp between 1943 and 1945. The last group was released in April 1946.

In terms of direct participation in the war effort, New Mexican servicemen actively participated in combat roles during World War II. A group of them suffered at the hands of Japanese captors in the Philippines in what became known as the Bataan Death March. In the summer of 1941, 1,800 New Mexicans attached to the 111th National Guard Cavalry were transferred to the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment for training as the United States prepared for the possibility of entry into World War II. The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor took place while the 200th and the 515th trained at Fort Stotsenburg, 75 miles north of Manila.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

On December 8, 1941, the day following Pearl Harbor, Japanese planes attacked Manila. The members of the 200th and 515th made their best effort to employ the anti-aircraft maneuvers that they had been training to perfect, but the Japanese onslaught proved too powerful. A combined U.S. and Filipino force of nearly 80,000 men retreated to a more defensible position on the Bataan Peninsula.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

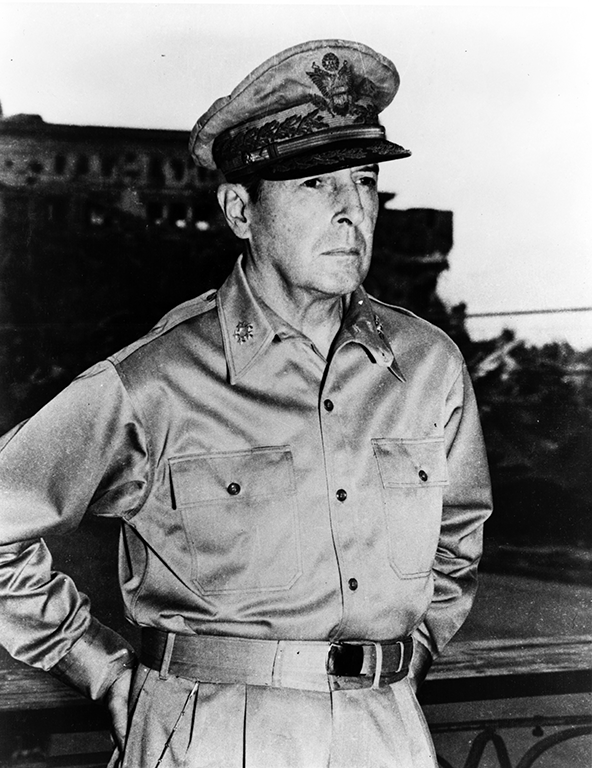

Over the next four months, they struggled to hold off the Japanese. General Douglas MacArthur initially believed that the men would be able to maintain their position for at least six months without additional supplies or reinforcements. On March 11, 1942, as food and medical supplies dwindled, MacArthur fled Bataan in order to secure aid. He stood by his famous parting words, “I shall return,” but he was delayed for a period of two years.

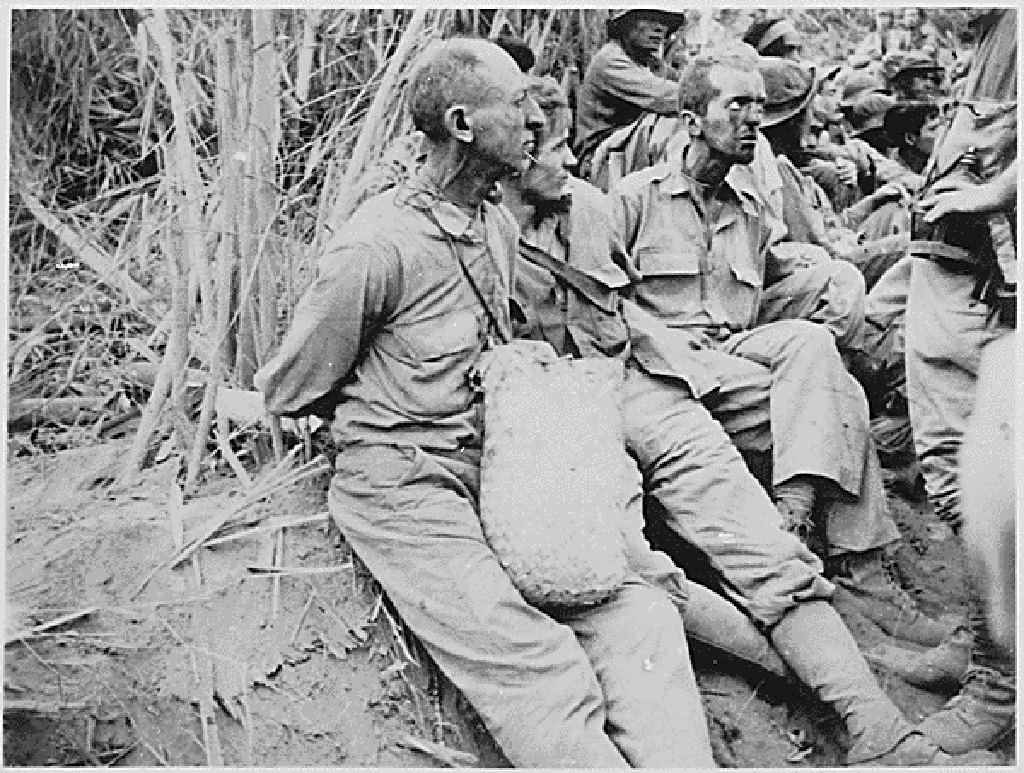

The combined U.S. and Filipino contingent surrendered on April 9. Along with about 20,000 Filipino civilians, the captives were forced to march a distance of sixty miles to the Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in sweltering heat. Many were wounded or weakened from the prior months of combat and shortage of food and supplies. The Japanese had horribly underestimated the number of men who had held out on the Bataan peninsula, and they were unprepared to evacuate all of them. Those who were unable to keep the pace, or who collapsed along the way, were summarily executed by their captors.

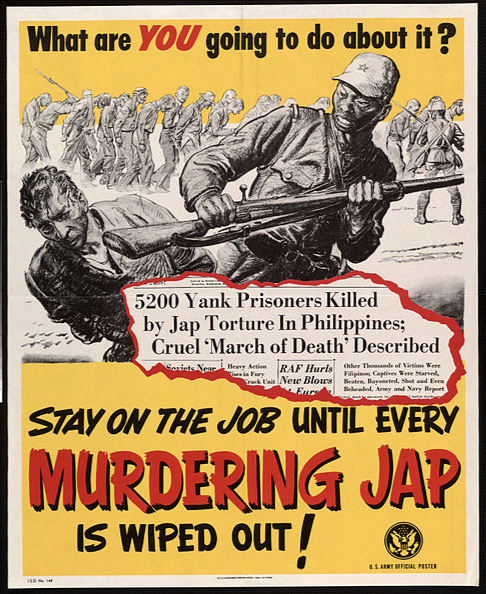

News of Japanese brutality at Bataan created outrage back in the United States. In all, about 10,000 men (1,000 Americans and 9,000 Filipinos) were either killed or died on the march. A propaganda campaign in the United States focused on the atrocities of the death march to call on Americans to support the war effort. Not until the late summer of 1945 were the surviving prisoners of war liberated. All were emaciated and some were unable to walk.

Nearly one-third of those rescued died of complications from the poor conditions in which they were held. About half of the 1,800 New Mexicans who served in the 200th died at Bataan. Memorials to the 987 survivors have been constructed in New Mexican towns across the state, and each March a Bataan Death March Memorial takes place at the White Sands Missile Range.

Navajo Code Talkers’ experience in the Pacific theater was markedly different. Even as Navajo people coped with federal livestock reduction programs on their lands, hundreds of them served with dignity in the U.S. military, as did thousands of other Native Americans across the country. Although not publicly known at the time, Navajos created an unbreakable code using their own language that facilitated communications and intelligence gathering. The Code Talkers’ crucial service was not made known until years after the fact because military officials believed that their services might be needed again as relations broke down between the United States and the Soviet Union in the years immediately following the war.

During World War I, a company of Choctaw men became the first to use their own language as a code for wartime radio communications. In 1940, prior to U.S. entry into the Second World War, the War Department approached the Bureau of Indian Affairs about the possibility of recruiting Native Americans for service in the Signal Corps. The Army program was somewhat small in scale. About fifty Comanche men served in the 4th Signal Company, but their services were only used sporadically. Most of their time was spent in regular combat operations.

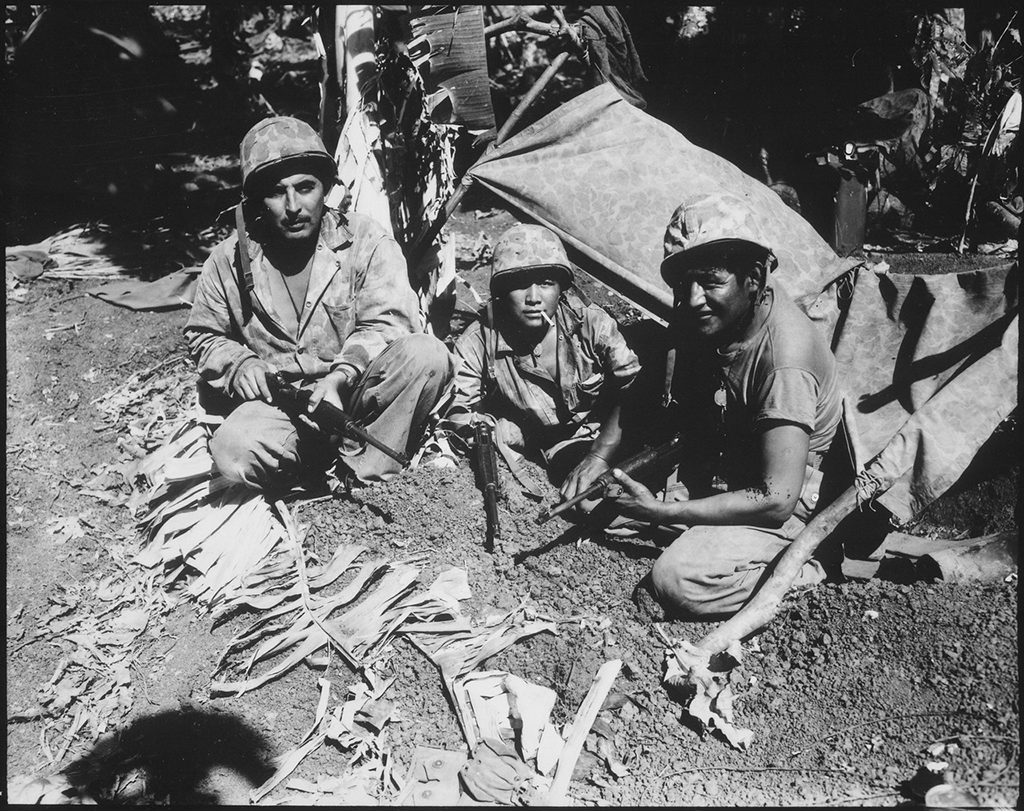

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

The Navajo Code Talkers recruited by the Marines played a far more significant role in the Pacific theater. Although not all Marine commanders were initially convinced of the wisdom of the program, the first thirty Navajo recruits entered boot camp at Camp Elliott, California, in May of 1942.10 Their first assignment was Guadalcanal, where their test transmissions initially caused American radio operators, unaware of the Navajos’ mission, to believe that Japanese soldiers had taken control of U.S. radio equipment.

Once the confusion was resolved, the Code Talkers took the lead in the transmission of both mundane and highly sensitive communications. Unlike African American soldiers who served in segregated units, Navajo marines (and all Native American servicemen) were integrated into existing units. Still, some Marines initially mistook them for Japanese soldiers. In one case, William McCabe was detained by a sentry when attempting to eat with other members of his platoon. The provost marshal nearly ordered him shot, but finally realized that he was indeed an American citizen. After a few such experiences, bodyguards were assigned to the Code Talkers. They were ordered “to never leave their sides.”11

In the present age of encryption technology, the voice code employed by the Code Talkers seems somewhat antiquated. During World War II, however, the Navajo Code Talkers boasted the only unbroken communications system in the Pacific theater. Their efforts greatly aided the war effort, but they were not recognized for their service for over a quarter-century. Security measures remained in place to ensure that the Navajo code would not become public knowledge.

As a result of continued secrecy, many Navajo servicemen felt abandoned by the military following their years of service. By the close of the war, 420 Navajo men had been trained by the Marines as Code Talkers. Upon returning home, many suffered the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in silence because they were unable to share the details of their wartime missions with family or friends. Ritual dances, such as the Nidaa’ or Enemy Way Ceremony, helped some to overcome their strife.

Code Talkers also faced difficulties rejoining civilian life due to its limitations on their civil rights. Despite equal treatment during their tenure in the Marines, members of the Navajo Nation were prohibited from voting in either Arizona or New Mexico and the continued restrictions on grazing meant that veterans were unable to reestablish their former herds.

Courtesy of U.S. Department of Defense

In other ways, the war provided the Code Talkers with new avenues for personal and economic growth. They led Diné efforts to address economic, political, and social inequity. Several, including Carl Gorman, obtained advanced degrees. They also supported lawsuits against the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the states of New Mexico and Arizona, and local municipalities, to gain rights they were denied. By the mid-1950s, Navajos had asserted their right to vote in all elections, from the local to the federal level.

At the 1969 reunion of the Fourth Marine Division held in Chicago, the organizers of the event decided to honor the Code Talkers. Despite the continuation of secrecy measures at higher levels of the military, for the first time their crucial contribution to the war effort became public knowledge. Over the next two decades, oral history projects and official ceremonies publicized the Code Talkers’ service. In 1981, for example, the Marines formed another Navajo platoon with twenty-nine members in honor of the original group of Code Talkers. The following year, Congress declared August 14 to be National Navajo Code Talkers Day. In 1993 an exhibit to honor the Code Talkers opened at the Pentagon.

During the early 2000s, the small group of surviving members of the original group of Code Talkers recounted their histories to biographers and conducted lectures in various places around the Southwest. On June 4, 2014, at age 93, Chester Nez was the last of that original group to pass away. A few of the Code Talkers who belonged to subsequent recruitment cycles are still alive, and they receive public honors from time-to-time, like those discussed by David Patterson in his video interview.