The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 15: Civil Rights Movements

- Civil Rights Movements

- Alianza de Mercedes Libres

- Chicano Community Organization

- African American Rights

- Indigenous Peoples' Civil Rights

- References & Further Reading

Although the national Chicano movement formed in the context of the gains made by African American civil rights activists in the early 1950s and Alianza followed some of the tactics initiated by black civil rights leaders, in New Mexico black civil rights advocates followed the lead of hispano activists. Such was the case due to the small number of African Americans in New Mexico. By some estimates, they never accounted for more than three percent of the state’s population during the period between 1950 and 1970.

Historian George M. Cooper has suggested that the 1954 Brown v. Board decision was not a significant watershed for New Mexico’s African American communities precisely because their numbers were so small. Not only were they few in number, but they were spread out in cities and towns throughout the state. Their separation meant that presenting a unified front was more difficult than was the case for nuevomexicanos or for African American activists in the Deep South.

Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico

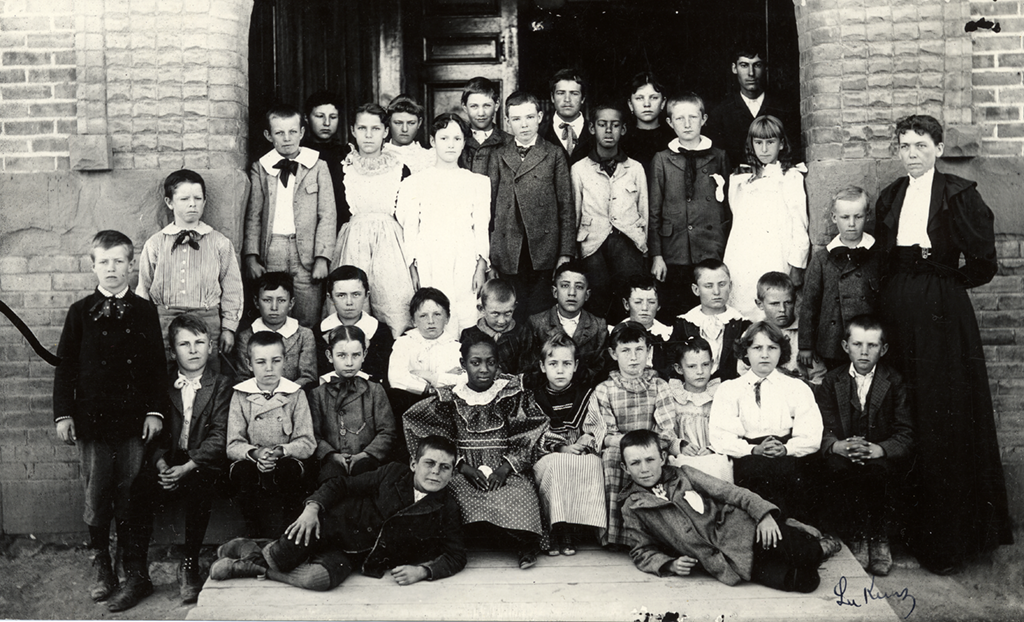

Additionally, as mentioned in the introduction, many New Mexican towns began to integrate schools prior to Brown v. Board. In Hobbs and Carlsbad, accreditation and a desire to conserve municipal funds were central to that decision.

In Albuquerque, the state’s largest city with the largest percentage of African American residents, de jure segregation of schools had never existed. In his 1969 report on blacks in Albuquerque, activist and Black Power advocate Roger W. Banks declared that the lack of segregated schools was not due to Albuquerque residents’ tendency toward integration. On the contrary, in the 1930s Albuquerque Public Schools had attempted to open a separate school for the city’s African American children but black families “refused this invitation to segregate themselves.”16

Black students in Albuquerque Public Schools sat at the back of classrooms and were forced to line up separately during commencement ceremonies. They were placed as a group at the center of the graduation procession to prevent them from leading their graduating class into or out of the arena in which the ceremonies were held.

Banks argued that Albuquerque’s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was a defensive, rather than an offensive, organization. It had been founded in 1915 to address the concerns of the local black community; access to education was among the first issues addressed. That same year, the NAACP challenged the University of New Mexico’s policy of excluding African Americans by funding Birdie Hardin’s admission application. Hardin’s application was rejected, but through the organization’s persistence, Romero Lewis became the first black student of UNM in 1921.

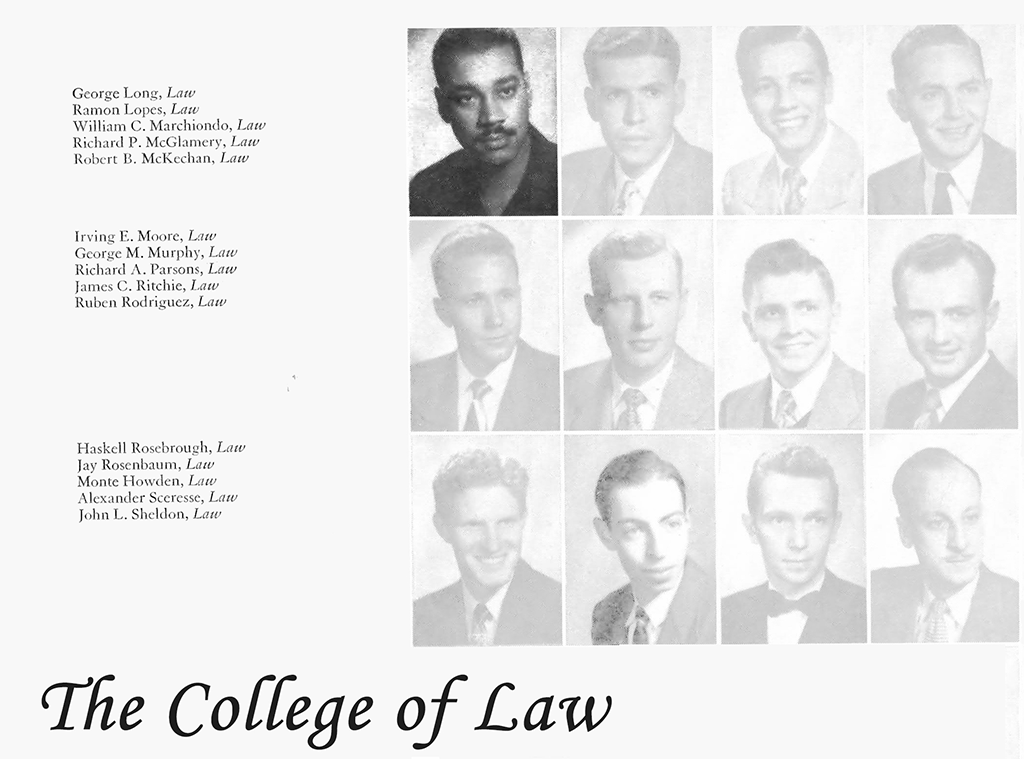

In the late-1940s, UNM became the focal point of a campaign to end racial discrimination in Albuquerque. On September 12, 1947, the editor of the student newspaper, The New Mexico Lobo, sent black student George Long and a reporter to Oklahoma Joe’s, a café near campus. The wait staff at the café refused service to the pair on the basis of Long’s race, and the Lobo published an account of the incident in its September 19 issue. The publicity given to Long’s experience, including a follow-up letter to the editor in the September 23 Lobo, initiated events that resulted in the passage of Albuquerque’s anti-discrimination ordinance in 1952.

Courtesy of University of New Mexico, Mirage Publication 1950

In the fall 1953 edition of the NAACP publication, Crisis, Long published an account of what had been dubbed “The George Long Incident.” Following the Lobo’s report, “a sizable group of irate students on campus” came together to demand that the student council convene to take action. When a special session of the student council met on September 18, the leaders declined to act on the issue of racial discrimination due to the “unimportance” of the issue, yet they did create a special investigation committee to further study the problem.17

Joe Fiensiler, owner of Oklahoma Joe’s, justified the actions of his staff by claiming that the café’s policy was in accordance with the practices of UNM fraternities. The investigating committee and student council seemed content with his response, but a majority of the student body refused to let the matter die. A voluntary student boycott of Oklahoma Joe’s, and subsequently a nearby Walgreens store, inspired a temporary change in the two establishments’ policies.

Courtesy of Carol Kaliff, The Danbury News-Times. © Hearst Connecticut Media Group

During the Walgreens boycott in January 1948, African American participants organized a student chapter of the NAACP. Herbert Wright, who later became the NAACP’s national youth director, became the chapter’s first president.

Wright and other members of the student chapter quickly realized that the boycott’s success was limited. Only two businesses had been impacted, and they had not committed to long-term anti-discrimination policies. Wright proposed a campaign for a city-wide anti-discrimination ordinance, based on similar legislation that had already been established in Portland, Oregon. With the support of the Albuquerque NAACP, the students worked to adjust the Portland law to the needs of Albuquerque.

Between June of 1948 and February of 1952, when the Albuquerque city council adopted the anti-discrimination ordinance, Wright and NAACP supporters worked tirelessly to advocate for the measure. Groups like the Ministerial Alliance, the G. I. Forum, labor unions, and the Catholic Archdiocese added their support for the legislation. Based on city council suggestions, Long, who had entered UNM’s law school, redrafted the ordinance several times before a final version was accepted.

Even after the wording had been finetuned, hurdles remained. In mid-October 1950 the city council appointed a special committee to investigate the extent of discrimination in Albuquerque. When the committee’s report reached the city council in November of 1951, it had concluded that discrimination in public places was minimal except “as regards members of the Negro race.”18 Committee members also reported that discrimination against African Americans was increasing and most members of the community supported the proposed legislation.

Despite a few impassioned speeches delivered in opposition to the measure during public readings of the bill, the ordinance became law on February 15, 1952. In its final form, the ordinance “prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, and national origin or ancestry” in “places of public accommodation.”19 Violators of the law were to be charged with a misdemeanor and fined between one hundred and three hundred dollars, depending on the severity of the offense.

By Long’s own account, within the first two years of the ordinance’s passage the vast majority of local businesses complied with its provisions, although there previously “were numerous public places that staunchly refused to serve Negroes no matter how many appeals were made to serve them.”20 In his 1953 article, he also wrote that the struggle was far from over. Equal rights in terms of employment and housing had not yet been accomplished for African Americans in New Mexico. Indeed, written covenants in many of Albuquerque’s subdivisions prohibited black residents and they remained on the books into the 1970s.

Courtesy of Blackpast.org

The South Broadway region of the city, also known as Census Tract Thirteen, was the place that most of the city’s African Americans inhabited. Most of them were of the working class, but some opened businesses including barber shops, cleaners, shoeshine parlors, and nightclubs. The first black church, the Grant Chapel AME Church, was also located there.

Activist Roger W. Banks referred to the South Broadway neighborhood as a space “between the tracks and the freeway.” Interstate 25 marked its eastern edge while the western border was defined by the railroad tracks that ran south of the present-day Alvarado transit center in downtown Albuquerque. Although Banks recognized the accomplishments achieved by the local NAACP, he also emphasized the fact that the anti-discrimination ordinance addressed middle-class concerns without taking the plight of working class blacks into consideration.

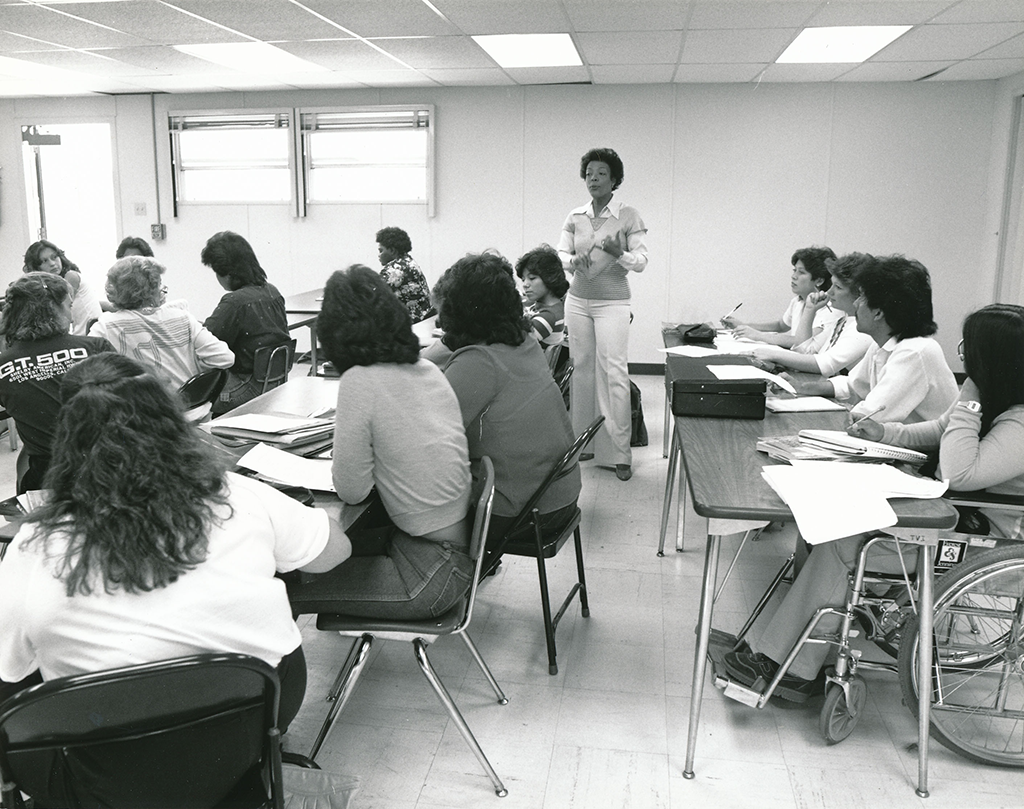

Courtesy of Central New Mexico Community College

Later analysts cite African Americans’ small numbers in explaining the relatively low profile of their activism in New Mexico during the civil rights era. Banks’ focus on class divisions, however, posits an alternate interpretation. He acknowledges that African Americans’ meager numbers kept them from being fully included in New Mexico’s political system. As the NAACP assumed a more active profile in Albuquerque during the 1950s, however, blacks in other towns in the state continued to face discrimination on a daily basis—especially in Little Texas.

Middle class blacks in Albuquerque had “become culturally, emotionally, economically, and geographically part of the white community,” according to Banks.21 Because of their economic affinity with whites and nuevomexicanos, they were not in a position to address the concerns of working class African Americans who comprised the majority of New Mexico’s black community.

Courtesy of Central New Mexico Community College

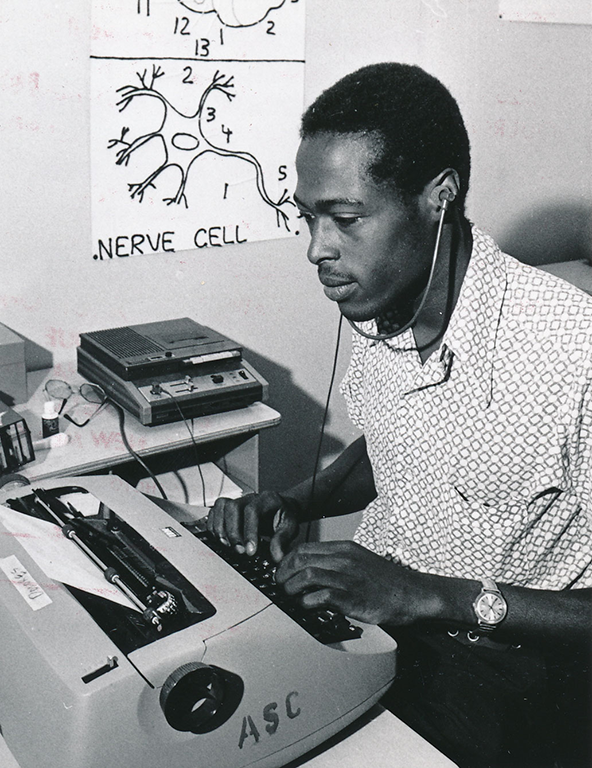

Among the concerns of working class African Americans were the desire to find gainful employment, receive educational opportunities, and thus break the cycle of poverty. Such concerns prevented African Americans in Census Tract Thirteen from joining Albuquerque’s social and political circles in the way that middle class blacks had done. For most of the neighborhood’s residents, poverty and transience defined daily life.

National civil rights militancy, including events in Watts, Atlanta, Washington, D.C, and Alianza’s occupation of sections of the Carson National Forest, soured white Albuquerque residents’ opinions of their African American neighbors in the mid-1960s. As a result of such perceptions, opportunities for education, decent housing, and employment diminished in Albuquerque during the 1960s. Throughout that decade, the unemployment rate for African Americans hovered at about eight percent—a figure that was twice that of the white unemployment rate.

In 1969, Banks painted a picture of Albuquerque blacks who were becoming increasingly frustrated with negative perceptions of them based on national events rather than anything they had actually done or said. His purpose was to advocate for the rise of more militant, Black Power actions in Albuquerque, and the problems he highlighted in his report were very real. Many African Americans in New Mexico took public action to alleviate the situation, and in 1963 the Albuquerque city council passed a Fair Housing Practices law to end discriminatory practices like the creation of covenants and riders that banned blacks from certain neighborhoods.

On March 27, 1960, in the small southeastern New Mexico town of Hobbs, college-age African Americans staged a sit-in at the McLellan store’s soda fountain. Their action came just less than two months after the more well-known sit-in at Greensboro, North Carolina. The local NAACP chapter (by the early 1960s, Hobbs, Roswell, Carlsbad, and Las Cruces also had an NAACP presence) supported legal actions, rather than public protest or demonstrations. Despite the lack of other civil rights organizations, like the Urban League or the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), New Mexican blacks demonstrated when opportunities arose.

The Hobbs sit-in only lasted for about fifteen minutes, but it generated a discussion about race and discrimination. Bud Peters, the manager on duty at the McLellan store, reported that “a couple of white customers left and that two white women got up and stood behind their husbands while the blacks remained at the counter.”22

As historian George M. Cooper has pointed out, the coverage of the sit-in by the Hobbs Daily News-Sun was troubling at best. A brief account of the demonstration occupied the front page spot that was typically reserved for the lead story. The article did not include a headline. Adjacent to it on the page, an Associate Press release appeared, also with no headline, which recounted Ku Klux Klan retaliation against protesters in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. Cooper concludes that the juxtaposition was “more of a warning to the students who participated in the sit-in at Hobbs than a serious attempt at reportage.”23

Courtesy of Hobbs Daily News-Sun

The situation in Hobbs highlighted a reality that all African Americans understood well in the early 1960s. The end of school segregation and the proposal of anti-discrimination ordinances were only first steps toward full equality before the law. Those who had staged the sit-in joined members of the Hobbs NAACP in advocating for legislation against discrimination at the municipal level. Their struggle eventually resulted in the eventual integration of Hobbs at the social level a few years later. For example, the requirement that African Americans enter the homes of whites through separate entrances was invalidated through such efforts.

Tensions between Chicano and African American Activists also characterized the period between 1950 and 1970. Despite the presence of Dr. Alton Davis, the black president of the American Emancipation Centennial, as the keynote speaker of Alianza’s first annual meeting and Tijerina’s work with Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Poor People’s Campaign, many nuevomexicanos believed that the subjugation of African Americans was not the same as the oppression that they faced themselves.

In a 2008 comment, meant to capture the feeling of the previous generation, Fernando C. de Baca remarked: “The truth is that Hispanics came here as conquerors, African Americans came here as slaves. . . . Hispanics consider themselves above blacks.”24 Although C. de Baca certainly did not speak for all nuevomexicanos of his father’s generation, his comment captures the sense of distrust that remained between African Americans and hispanos in New Mexico, even as some individuals of the two ethnic groups tried to foster cooperation in support of civil rights for all.

Courtesy of the Albuquerque Journal

Placed in the context of their extremely small numbers, the civil rights achievements of African American activists in New Mexico are striking. Unfortunately, their struggle and the struggle of Chicanos, Native Americans, Asian Americans, women, and LGBT people for equality before the law continues.