The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 15: Civil Rights Movements

- Civil Rights Movements

- Alianza de Mercedes Libres

- Chicano Community Organization

- African American Rights

- Indigenous Peoples' Civil Rights

- References & Further Reading

A fiery orator and militant leader from Texas, Reies López Tijerina, emerged as the unlikely face of the Chicano civil rights movement in northern New Mexico. Although some scholars have asserted the notion that New Mexico was minimally impacted by the Chicano movement, more recent studies indicate that many nuevomexicanos supported el movimiento’s (as participants referred to Chicano activism) struggle for civil rights.

Unlike earlier strains of Spanish American ethnic identity, Chicanos proudly asserted their dual heritage as descendants of Spanish conquistadores and indigenous peoples. The idea that the Mexica homeland, or Aztlán, was located somewhere in the modern U.S. Southwest bolstered Chicano claims on that region. Chicano activists in southern California, Colorado, and elsewhere in the nation focused on issues ranging from agricultural working conditions, to school segregation, to cultural expressions of Americanism. In New Mexico, Tijerina galvanized ongoing nuevomexicano efforts to restore lost lands.

Reies López Tijerina was born in Falls City, Texas, in 1923 to a Mexican-origin working class family. Spanish was his native language; he did not learn to speak English until he was about twelve years old. As a teenager, he participated in a three-year Assembly of God education program near El Paso. Upon graduation at age eighteen, Tijerina worked as an evangelical missionary on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. His religious background informed the tone of his later activism.

In 1957, Tijerina organized a cooperative village in southern Arizona called Valley of Peace. Local agriculturists and mining interests, however, opposed his moves to help working-class hispanos gain a modicum of economic independence. Resistance to the community forced Tijerina to relocate with his family to northern New Mexico where he intended to continue his ministry and his organization of Mexican Americans in support of their economic, social, and political rights.

Tijerina had first visited Rio Arriba County in the 1940s and since that time had maintained ties with La Mano Negra (the Black Hand), a clandestine organization that sought the restoration of land and resource rights to nuevomexicano heirs of Spanish and Mexican land grants. When he settled in New Mexico in 1959, his commitment to nuevomexicano land disputes solidified. He saw the land grant heirs as people with cultural, historical, and numerical strength. Within the existing class and political structure of New Mexico, Tijerina believed that nuevomexicanos “could make their rights felt in the eyes of the government.”3

As geographer David Correia reminds us, heirs of the Tierra Amarilla land grant engaged in militant activism prior to Tijerina’s arrival. Those associated with La Mano Negra destroyed fences and barns, and attempted to intimidate outsiders looking to purchase grant lands, much as had been the case with Las Gorras Blancas in the late nineteenth century. In the late 1930s, land grant heirs had also organized La Corporación de Abiquíu which sought to work within the legal system to restore rights to lands and resources.

When Tijerina arrived in northern New Mexico in the late 1950s, conditions were ripe for another phase of land grant activism. Fernanda Martínez and Gregorita Aguilar taught Tijerina the long, contested history of the Tierra Amarilla land grant. They also introduced him to members of local advocacy groups and informed him of their methods and approaches. Tijerina provided the existing movement with national notoriety and connections to other civil rights groups. It is crucial to understand his central role in the land grant activism of the 1960s, but to also recognize the long historical roots of the struggle.

Courtesy of Peter Nabokov

On February 2, 1963, the anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Tijerina and his supporters founded the Alianza Federal de Mercedes Libres (Federal Alliance for Free Land Grants). Alianza attempted to bring together all heirs of land grants that had been in existence when the treaty had been formalized in 1848. In organizing Alianza, Tijerina asserted that “none of these grant lands and waters which the United States asserts it acquired from Mexico under the treaty . . . ever formed any part of the public domain. These lands and waters therefore cannot be taken for that purpose.”4

Tijerina’s arguments were based on diligent research that he conducted in the archives of Madrid, Mexico City, and Santa Fe. As Alianza made claims for the restoration of northern New Mexico land grants, in particular the San Joaquín del Río Chama and Tierra Amarilla grants, the group cited the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Recopilación de leyes de las Indias, a seventeenth-century Spanish legal tract. The Recopilación helped Alianza to establish the original delineation of New Mexican land grants, and, according to the group, the U.S. government had violated articles VIII and IX of the 1848 treaty. Those were the articles that had guaranteed U.S. citizenship and property rights to former residents of Mexico.

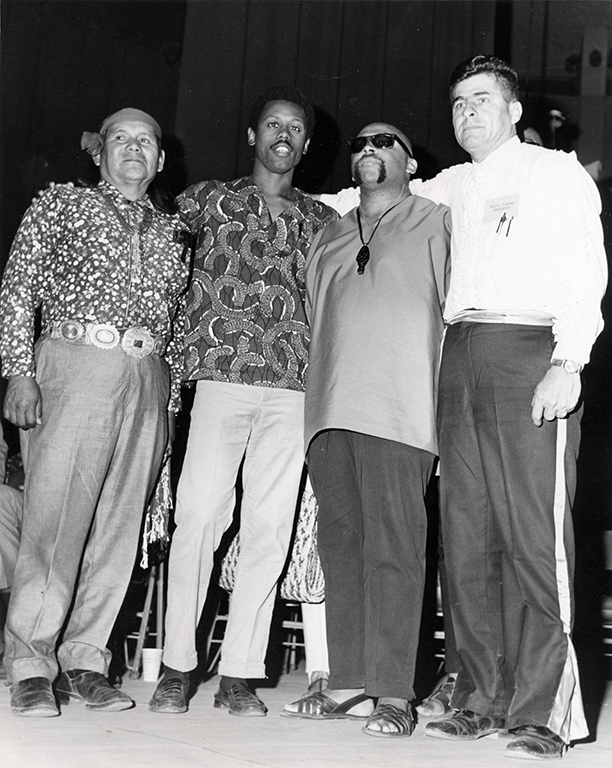

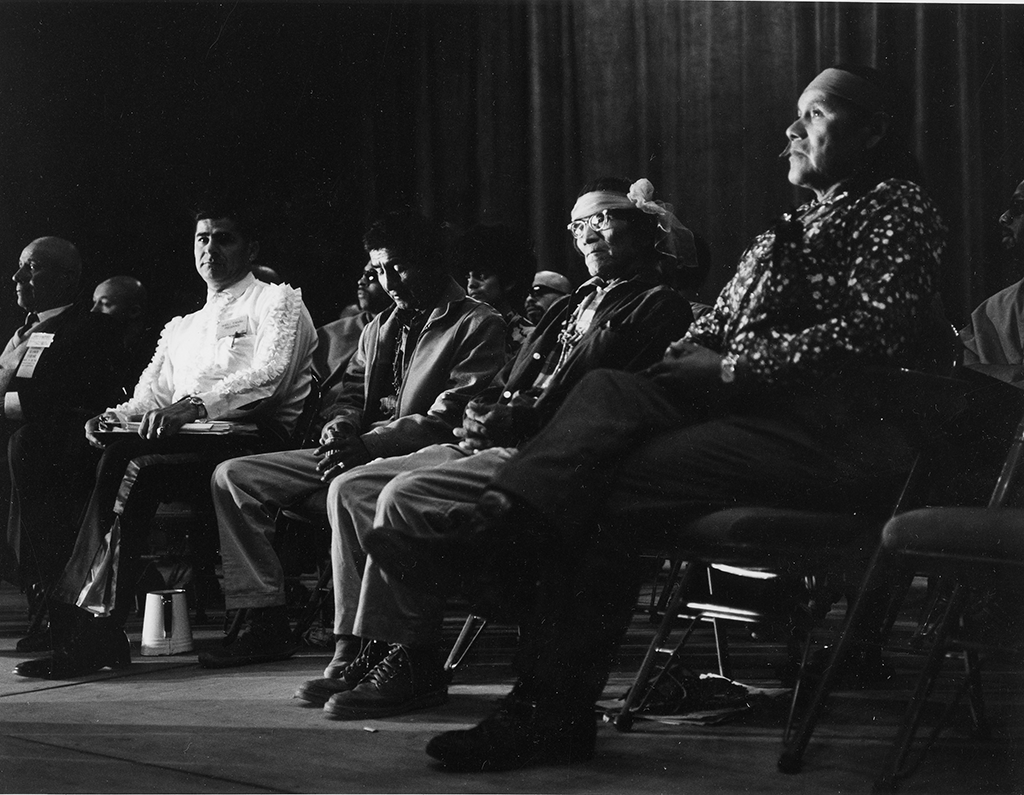

In an effort to legitimate Alianza’s efforts and gain wider support, Tijerina worked to build connections to other civil rights leaders. He also attempted to foster international solidarity by meeting with Mexican president Luis Echeverría and other high-level officials. To a greater degree than most other Chicano leaders, including Rodolfo “Corky” González, César Chávez, and Dolores Huerta, Tijerina sought to forge ties with African American and Native American civil rights leaders.

Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

In 1967 and 1968, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. became increasingly convinced that the plight of poverty united minority groups seeking citizenship rights, Tijerina joined him in organizing the Poor People’s Campaign. King was assassinated before the Poor People’s March on Washington took place, but on May 12, 1968, Reverends Ralph D. Abernathy and Jesse Jackson, along with Tijerina, led the march in a vow to continue the work that King had begun. Tijerina also sought to make connections with Native American civil rights leaders. He believed that:

We have been forced by destiny to adopt two languages; we will be the future ambassadors to Latin America. At home, I believe the Southwest is breeding a special kind of people that will bridge the color gap between black and white. It will be brown that fills the gap. . . . We are the people the Indians call their ‘lost brothers.’5

Despite such efforts, Tijerina’s increasing reliance upon militant and overtly violent methods attracted much criticism and split his support along class lines. For years, scholars have followed the official narrative on Alianza and Tijerina in reporting that his combination of militancy and religious zeal espoused violence. More recently, however, David Correia has shown that state violence against Alianza intensified the militancy of both sides. Religious zeal no doubt also played into Tijerina’s, and Alianza’s, response to state violence.6 The FBI targeted militant civil rights advocates like Tijerina, as well as those who advocated nonviolent methods, like King.

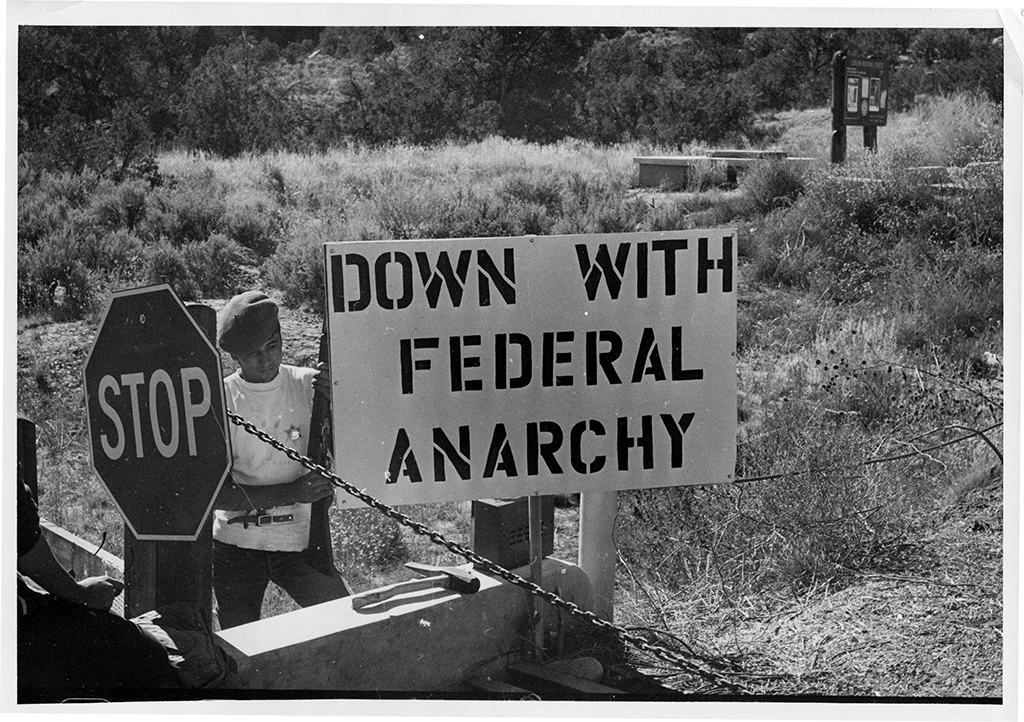

Alianza not only attempted to restore land grant rights by appeals to centuries’ old documents. Under Tijerina’s leadership, the group also tried to forcibly retake control of lands granted under Spanish and Mexican law, and guaranteed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In order to stake the claims of land grant heirs, Alianza set up the Republic of San Joaquín del Río Chama in the Kit Carson National Forest in 1966. That October, a confrontation occurred between forest rangers and Alianza members. Alianza took three rangers prisoner, convicted them of trespassing on their lands, granted them suspended sentences, and released them, along with their trucks. Tijerina avoided arrest in this instance, but federal and state law enforcement agents, including FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, more closely monitored his activities.

Courtesy of Peter Nabokov

On June 5, 1967, Tijerina led a group of twenty Aliancistas (members of Alianza) in a daylight raid of the Rio Arriba County Courthouse located in the small town of Tierra Amarilla. Their goal was to make a citizens’ arrest of district attorney Alfonso Sánchez in response to his efforts to prevent Alianza members from gathering and organizing meetings. Aliancistas charged Sánchez’s actions, which included setting up roadblocks and arresting Aliancistas on outdated charges, violated their First Amendment right to assembly.

Sánchez did not present himself at the courthouse. As they sought to locate him, the Aliancistas shot and wounded a state police officer and a jailer before fleeing into nearby mountains with two hostages. The prisoners were soon freed, and most of the Aliancistas surrendered within two days of the raid. E. Lee Francis, New Mexico’s lieutenant governor who was in charge because Governor David Cargo was out of the state at the time, ordered municipal law enforcement agencies to join efforts led by the state National Guard to locate Tijerina who eluded authorities in the mountains near Canjilón.

State troopers had already been working in coordination with FBI agents to undermine Alianza efforts. During the manhunt, the combined law enforcement detail used two tanks, several helicopters, spotter planes, a hospital van, and patrol jeeps to search for Tijerina. When they were unable to locate him, a group of about fifty nuevomexicanos, including men, women, and children, were detained in the elements without shelter, food, or water as bait to force Tijerina’s surrender. Within five days of the raid, Tijerina submitted to the authorities.

Following his arrest, Tijerina was charged with fifty-four criminal counts, including kidnapping and armed assault. The courthouse raid drew television crews and journalists to the area and brought Alianza’s struggle to restore Spanish- and Mexican-era land grants to the nation’s attention. Some heralded Tijerina as a hero of an oppressed group of people; others emphasized the “backward” and seemingly pre-modern lifeways and culture of nuevomexicano people at the heart of the struggle. That more stereotypical perspective appeared in an NBC report on the raid that aired in 1967.

Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico

The courthouse raid also galvanized local divisions over Tijerina’s actions. Those belonging to the rico nuevomexicano old guard considered Tijerina an outsider and a troublemaker who merely wanted to make a name for himself at the expense of local communities. Senator Joseph Sánchez—at the time the highest-ranking hispano politician in New Mexico, for example, lashed out against Tijerina. He declared that the “last thing the Spanish-speaking need is agitation, rabble rousing, or creation of false hopes,” all ostensibly things that Tijerina was responsible for.7

Indeed, the general sentiment in mid-1960s New Mexico was that any action should be avoided that might create racial tension. In recent years, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s central role in the history of New Mexico has been recognized by scholars and residents of the Southwest alike. Such was not the case in the 1960s. At that time, efforts to highlight the economic, social, and political inequalities rampant in New Mexico was cast as an attempt to stir up racial animosities and cause trouble. The Albuquerque Tribune considered Tijerina within that context. In 1967 the paper reported that the land grant movement was a “fraudulent effort to read Spanish-Americans out of the white race,” and thus as a “reprehensible attempt to divide and exploit.”8

When he was brought to trial, Tijerina dismissed his attorneys in a ploy to buy more time. Instead, the judge told him that he had thirty minutes to prepare his own defense. Under pressure, he argued that those involved in the courthouse raid simply hoped to make a citizens’ arrest of district attorney Sánchez in order to assert their constitutional right to assembly. The prosecution was not prepared for his line of argumentation, nor his moving oratory, and the trial concluded with the acquittal of all charges.

Despite the victory in court, federal and state agencies intensified their efforts to dissolve Alianza and imprison Tijerina. At that point, counterinsurgency methods were employed by the FBI to deny the legitimacy of Alianza’s actions. Tijerina himself was dubbed a communist sympathizer in the press, despite his personal opposition to communist economic ideologies. During the Cold War, however, to be labeled a communist was to be labeled an enemy to the national good.

Courtesy of Peter Nabokov

The labeling of Alianza leaders was not simply the work of the media. In 1964 J. Edgar Hoover had requested that a special index be established to keep track of alleged communist influences on civil rights groups. As far as the FBI was concerned, movements to promote the civil rights of groups considered to be racial minorities were inherently subversive and threatening to the interests of the United States. By 1967, Hoover created the “Rabble Rouser Index,” a system to identify and undermine the actions of “racial agitators and individuals who have demonstrated a potential for fomenting racial discord.”9

By 1968, the Rabble Rouser Index was renamed the Agitator Index. Hoover directed agents in FBI field offices to draw up “wide-ranging and detailed plans of action against Rabble Rouser targets.”10 Tijerina was identified as one of the key Rabble Rousers or Agitators worthy of special action. Following his acquittal and release in December 1968, FBI agents intensified efforts to undermine Alianza. The homes of Aliancistas were mysteriously firebombed, and no official investigations made. According to the records of the Albuquerque FBI field office, “due to the controversial nature of the group, no investigation shall be conducted.”11

In May of 1968, a former New Mexico state trooper and federal marshal named Tiny Fellion severed his own left hand while placing an explosive device at the Alianza headquarters in Albuquerque. An earlier FBI report indicates that bureau officials enlisted his services because of his expertise in explosives. He was a paid assassin.

Late in 1968, Tijerina was once again placed on trial. His wife had set fire to a forest service sign, but he took the blame for the action and was arrested. The judge in the case revoked his bail from the 1967 conviction and once again charged him for his participation in the courthouse raid. Despite defense appeals to prohibitions on double jeopardy, the 1968 trial resulted in Tijerina’s conviction. He was sentenced to serve a prison term first at the Federal Correctional Facility at La Tuna in Anthony, New Mexico, and he was later moved to the federal facility at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Between 1969 and 1971, Tijerina served his sentence. During that period, Alianza’s activities and legitimacy declined. Following his release in 1971, Tijerina himself declared that he had “outgrown militancy,” and he adopted a softer line toward land grant issues—although he never gave up the struggle for the restoration of land and water rights in northern New Mexico until his death in January of 2015.12

Based on his changed attitude, various rumors surfaced that Tijerina had been tortured during his time in prison. By his own account, prison guards at Fort Leavenworth forced him to take medication for dementia that caused him to lose the use of his limbs. During his paralysis, he believed that the medication was going to kill him.

While he was imprisoned, members of his family and Aliancistas endured acts of terror by federal agents. Tijerina testified:

My wife was violated by police. My daughter Rose was kidnapped by police. My son Noé was kidnapped and raped by police. My home and office were bombed four times by police . . . And why all this terror? What is the motive for all this terror? The State and Federal Government will stop at nothing to cover up the ruthless raping of all our municipalities that were created under the Governments of Spain and Mexico. The stealing of our property rights is the real motive behind all this terror. This is the reason for denying me and my wife our constitutional rights.13

Investigations carried out by the Senate committee led by Frank Church in 1975, known as the Church Committee, determined that FBI activities toward domestic civil rights groups “violated the law and fundamental human decency.” The damning report went on to conclude that “the Bureau went beyond the collection of intelligence to secret action defined to ‘disrupt’ and ‘neutralize’ target groups and individuals.”14 The findings were little consolation to Alianza members, but their actions did result in important changes in northern New Mexico.