The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 15: Civil Rights Movements

- Civil Rights Movements

- Alianza de Mercedes Libres

- Chicano Community Organization

- African American Rights

- Indigenous Peoples' Civil Rights

- References & Further Reading

In 1935 Harold and Bessie Mae Kent traveled from Hollis, Oklahoma, to Tucumcari, New Mexico, in search of rumored job opportunities. The African American couple found the work they sought and made Tucumcari their home. Harold earned a secure income from his position at the Pelzer Motor Company, and then as a porter on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Eventually, he operated a small grocery store on the north side of town.

On May 26, 1938, the Kent’s first daughter, Haroldie, was born. Over the next few years the births of other sons and daughters—Alice, Sammie, and Frances—rounded out their family. During an oral history interview in the summer of 2001, Haroldie recalled her family’s middle-class status in contrast to the living conditions endured by poorer blacks in Tucumcari. Her parents had received very little education, and they worked tirelessly to provide better opportunities for their children.

Others were not so fortunate. When she was young, Haroldie had friends among the poorer African Americans in Tucumcari. She reflected on the one-room house inhabited by of one of the families. At least six people lived in the small space, and the cereal the family ate for dinner was diluted with water to make it go farther. Haroldie had never experienced such poverty, and she recounted that the members of her family “were pretty well off for blacks.”1

During Haroldie’s childhood, Tucumcari’s neighborhoods were segregated along racial lines. North of the railroad tracks, the most prominent feature in the town’s built landscape, African Americans and hispanos resided. On the south side were the homes of the white residents and a few of the wealthier nuevomexicanos. The majority of the Hispanos identified as Spanish American; Haroldie recalled that they considered the title “Mexican” to be degrading.

Haroldie could not recall many fights between people of different racial backgrounds, but they did occur. Her brother, Sammie, remembered that when fights broke out among the children or teenagers the whites and nuevomexicanos called the blacks, “niggers.” Near the end of his junior year in high school, Sammie broke up a fight between one of the other black girls and his sister, Frances. When the other girl brandished a knife and cut Frances’ hand, Sammie took the knife from her and ended the confrontation which occurred near the school grounds.

“Tootsie” Velasquez, police chief and Sammie’s boxing coach, arrived on the scene and arrested Sammie. “For some reason they apprehended me even though I wasn’t involved in the fight other than taking the knife from the girl who had cut my sister,” by Sammie’s account. During a hearing, Velasquez and several teachers testified that Sammie had been the center of the conflict. He spent ten days in jail and was unable to complete his junior year of high school. Fortunately, based on his above average grades, school officials allowed him to continue on to his senior year when he was elected vice president of his graduating class.

Haroldie and Sammie’s recollections paint a picture of institutionalized racism and discrimination. By her own admission, Haroldie never gave much thought to the fact that members of her family and the close-knit local black community were required to enter restaurants through the back door and eat in a dining room separate from whites and nuevomexicanos. Blacks also had to sit in the balcony seats at the local movie theaters, African American travelers were not allowed to stay in the whites-only hotels, and black children attended separate schools located on the north side of town.

According to Haroldie, “We never questioned why. We just accepted it until the civil rights movement, when we said we would not accept it anymore.”2 She adopted a live-and-let-live attitude, and believed that people should learn their place in society. Her sister, Alice, however, did not share this sentiment; she always resented the different treatment afforded to African Americans. Alice became heavily involved with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the civil rights movement.

“We never questioned why. We just accepted it until the civil rights movement, when we said we would not accept it anymore.”

Sammie’s attitude fell somewhere in between those of his sisters. He recognized the injustice of Jim Crow segregation and discrimination, even in the comparatively mild forms expressed in Tucumcari. For the most part he accepted the situation, although not all of his friends did. On one occasion, he went to a hamburger restaurant with a nuevomexicano friend. When the proprietor refused to allow Sammie to eat there, his friend declared that he would not eat there either unless they served Sammie.

As was the case in the national African American civil rights movement, many blacks in New Mexico considered school desegregation to be a first step toward ending discrimination at other levels of society. Tucumcari’s elementary and middle schools were segregated, but the closest segregated high school was in Clovis, a little over eighty miles distant. African American students who wished to attend high school had to move to Clovis and live with family or friends until Harold Kent petitioned the state legislature with the support of sympathetic white community members, like Dr. Thomas Gordon and his wife, Helen. As a result, in 1952, Tucumcari’s high school was integrated.

Most of New Mexico’s high schools integrated prior to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that initiated school integration on a national level. Segregation impacted not only the African American population (which comprised about three percent of New Mexico’s total population in the period between 1950 and 1970) but also nuevomexicanos and the children of Mexican immigrants—especially in the southeastern quadrant of the state known as Little Texas. Additionally, Native American students attended schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and were thus segregated.

Towns like Clovis, Hobbs, Carlsbad, Artesia, Roswell, and Las Cruces maintained segregated elementary and high schools into the early 1950s. No state-level mandate ever existed for the racial separation of students; all segregation policies were formulated at the municipal level. Some historians have noted that although nearly all of these towns integrated their school systems prior to Brown v. Board, the reasoning behind the change often had more to do with economics than a concern for equality. Carlsbad, for example, integrated its high school in the summer of 1951 to avoid the cost of updating the all-black high school in order to bring it into accreditation compliance. And, school integration was only a step toward equality in civil rights. Neighborhoods throughout the state continued in a state of de facto racial and economic segregation.

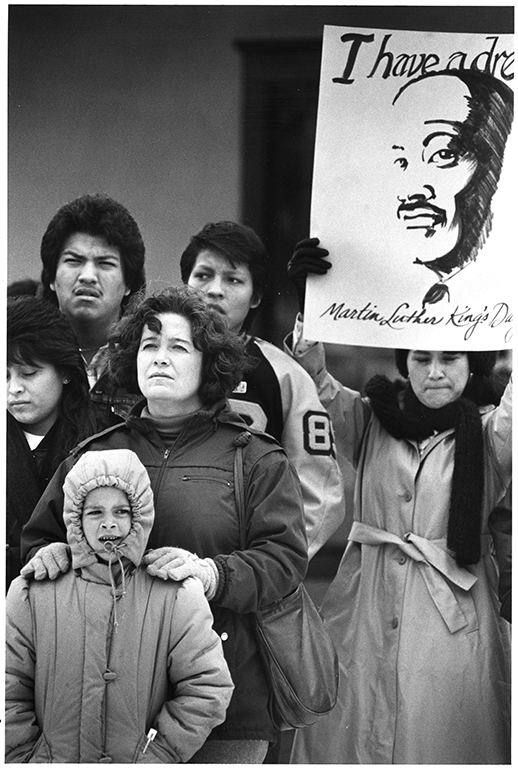

Courtesy of Mark G. Bralley

Civil rights movements in New Mexico, as in the rest of the nation, were multifaceted. The overall goal was to gain access to rights and privileges of U.S. citizenship on a daily basis, no matter a person’s ethnic background. Such struggles had been ongoing in New Mexico since 1848 when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo transferred the Southwest to the United States. During the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, however, African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanic Americans organized across the nation to advocate for equal rights before the law.

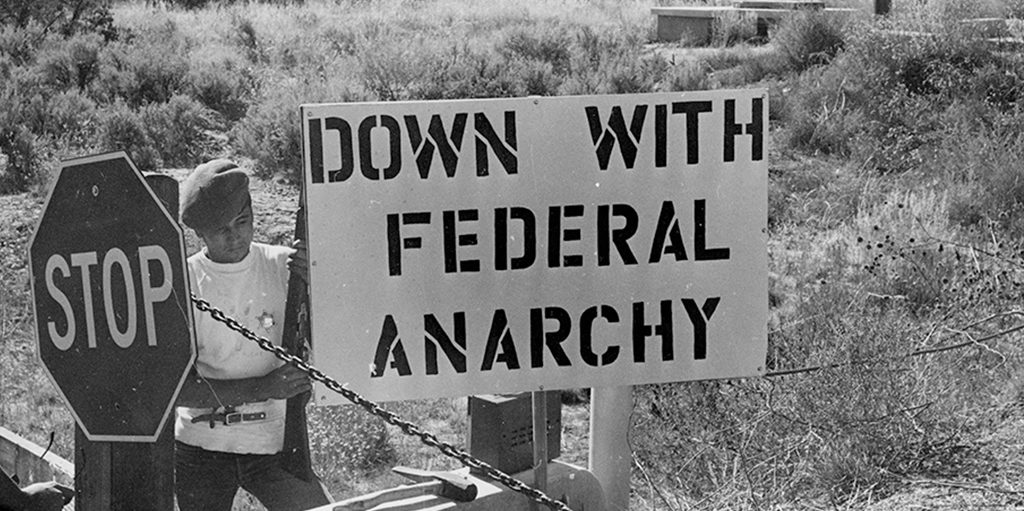

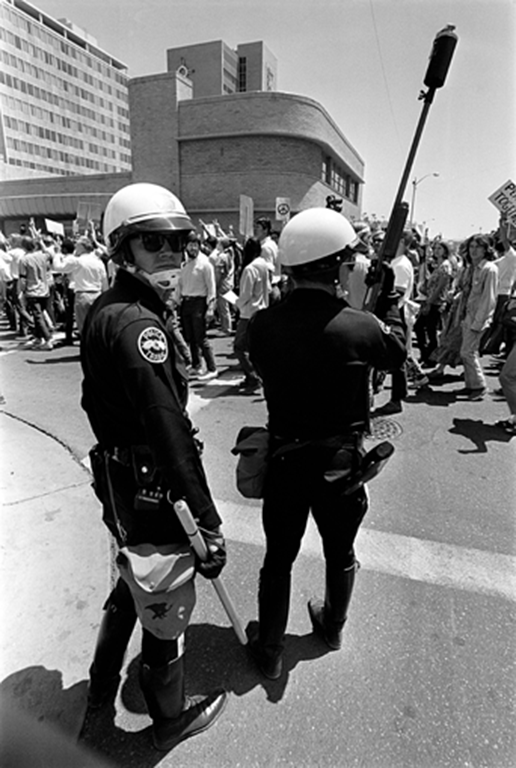

Within each civil rights movement were leaders who espoused non-violence, militancy, and middle-ground measures to achieve their ends. Reies López Tijerina emerged as the face of a militant movement to achieve the restoration of nuevomexicano land grants. Some hispanos and participants in the broader Chicano movement, however, opposed his methods and opted instead for peaceful protests. Similar patterns emerged within the Native American and African American movements.

Sydney Brink (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. HP.2014.14.748.v

Whatever the methods, civil rights advocacy ended ongoing de jure, or legally sanctioned, segregation in schools, at restaurants, and other public facilities across the state. Despite the gains, de facto, or unofficially sanctioned, segregation and discrimination continued. Many of the factors that comprise a person’s racial identification—including economic, educational, and residential opportunity—meant that people of certain racial backgrounds continued to live in neighborhoods dominated by people of their race.

The civil rights struggles of the mid-to-late twentieth century provided new legal recognitions of equality, but they did not end the ways in which racial discrimination had been institutionalized in social conventions or daily practices. In many ways, the struggle for equal rights for all continues.