You Are Not a Human Being Having a Spiritual Experience. You Are a Spiritual Being Having a Human Experience. –attributed to Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (popularized by Wayne Dyer)

In 1999 I was in Rome, Italy, for an excavation at the Villa of Livia in Prima Porta. One day, some Swedes and I were walking around Rome and decided to go to the Vatican. We simply walked into Saint Peter’s Square and suddenly I was swept up in a huge roar of a crowd. Thousands of people were crammed into the square, people had signs, and piñata-like things on sticks. Their glowing faces were looking up at a balcony.

“What’s happening?” I asked the Swedes, who looked bored.

“Oh, it’s the Pope,” they shrugged.

“WHAT?!?” I immediately worked my way to the center of the square, surrounded by sweaty ecstatic people. As I turned my head toward the balcony I caught sight of an arm waving and some white cloth flapping in the breeze.

“IT’S THE POPE!!” I shouted.

The Pope vanished and another huge wave of sound enveloped me and reverberated throughout the square. Only later did I question what happened at the moment and my reaction to seeing Pope John Paul was so moving. I mean, my parents forced me to go to the Catholic school on Saturday and I hated it so much that one day I just decided to get on my bike and ride as far and fast as I could. I kept this up for weeks until my brother snitched on me. Why then was I so caught up in this moment? Looking back, I think it was something called “collective effervescence”–a moment of spiritual ecstasy when a group is in perfect synchrony and solidarity. It is a feeling of oneness with other people that is irresistible to people. Well, except for the Swedes.

Spiritual Beings

A central irony of being human is that our spiritual nature is as notable as our ability to solve physical problems—we live in and excel in both realms. Humans invest huge amounts of time, energy, and money in planning and participating in religious activities, often preparing for weddings, funerals, and coming-of-age ceremonies years in advance. Monuments like Angkor Wat in Cambodia, Karnak in Egypt, the Parthenon in Greece, Tikal in Guatemala, and Stonehenge in England, to name a few, illustrate the lengths to which humans will go for the sake of spiritual beliefs. Plans are currently underway in India to build Viraat Ramayan Mandir, a religious complex even larger than Angkor Wat, the world’s largest. While chimpanzees display at waterfalls and throw rocks at particular trees, spirituality, religion, and sacred values take center stage in human societies. For many, spiritual or religious beliefs are at the core of a person’s life and identity.

There are dozens of major religions and around 4,000–5,000 in total. By some estimates, there are as many as 10,000 religions today, counting numerous sects or sub-religions (Dietrich 2015). Our devotion and industry toward matters of religion and ritual are so strong, that psychologist Jonathan Haidt suggests Homo spiritualis (spiritual human) is a better description of our species than Homo sapiens (thinking or wise man).

Supernatural and Religion

We can define supernatural as powers or phenomena that are not subject to the laws of nature. What qualifies as supernatural varies from culture to culture. Disease, for example, in Western societies is often considered a natural occurrence, caused by small organisms that invade the body or other biological processes. In other cultures, diseases are thought to be the result of supernatural forces. Among the Gebusi of Papua New Guinea, all adult deaths are considered to be caused by sorcery (Knauft 2013). The same was true for the Huaorani of Ecuador. As Anthropologist Steve Beckerman puts it, “There was no concept of accidental death or injury. If I’m out hunting and a tree branch falls and almost hits me, that’s witchcraft. Somebody caused that to happen” (Beckerman et al. 2009). Similarly, stars and planets are thought by some to personally affect lives, but for others, celestial objects are irrelevant to personal welfare. This contrast in supernatural beliefs can be seen in the ebola outbreak mentioned in Chapter 1. For the medical workers, ebola was a purely natural problem, but for some African villagers it was a kind of supernatural curse and medical workers were suspect (Bloch 2014).

All cultures have some form of religion, and thus religion is considered a cultural universal. Religion, like culture, has been defined in various ways. For many non-Western societies, there is no distinct and separate concept of religion at all. In Genealogies of Religion Talal Asad argues that the term “religion” is a modern European construction and can’t easily be applied to non-Western religions. Religion is simply the way the universe is organized—the “cosmic order” of things. Laws, rituals, and social norms, in turn, reflect this cosmic order. Religion is so embedded in daily life, that it doesn’t require a special name.

Anthropologist Sir Edmund B. Tylor (1832–1937) defined religion as simply belief in spiritual beings. His ideas about religion were based on progressivism. He thought that religions progressed over time as societies became more complex, from simple animistic beliefs to polytheism, to monotheism, and then finally to a scientific point of view. “Primitive” religions, in Tylor’s view, arose from the idea that so-called “primitive” people had dreams and assumed those dreams were a kind of separate, spiritual reality. Souls of people, animals, and the dead could travel and meet in this dream state. From there, people ascribed souls, spirits, or consciousness to nature—rocks, trees, mountains—assigning a kind of “personhood” to the natural world. This type of belief system is called animism.

For philosopher and psychologist William James (1842–1910), who wrote Varieties of Religious Experience, religion meant belief in an unseen order. Anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1926–2006), one of the most influential cultural anthropologists of the twentieth century, refers to religion as an order of existence supported by symbols that make that order seem obvious, natural, and factual. Though religion is difficult and possibly impossible to universally define, we can say that religion is widely shared in society, involves belief in a supernatural or cosmic order, and is supported by symbols and symbolic behavior.

Rituals

For Geertz, rituals support and confirm the “unseen order” of things. Rituals, like marriage, are cultural universals that vary widely from culture to culture. The features of rituals are the following:

(1) are symbolic

(2) create a sense of community or communitas

(3) create or prevent a transformation of some kind through the supernatural

(4) reflect ideologies or ideas about social correctness and the correct order of the universe

These are the defining characteristics of rituals. The idea of transformation is central to the concept of ritual. A Yanomami shaman, or part-time religious practitioner, might conduct a healing ceremony, contacting the spirit realm, to prevent someone from dying—preventing a transformation from life to death. Men of the island of Vanuatu in the South Pacific perform a land-diving ceremony, enjoining supernatural entities to provide a decent harvest and bring prosperity to the people—ensuring the transformation of a bountiful harvest. In parts of India a “baby dropping” ceremony, where infants are dropped from a building and caught below on a sheet, is intended to ensure that the infant will be strong and healthy and lead a long life—enacting a transformation from vulnerable to invulnerable. We simply don’t see anything like this outside of human societies. In all these cases, the supernatural is mobilized through the ritual to create or prevent some kind of change in the material world. The idea that rituals transform is not just a feature of non-Western societies. In one recent study, American young children assumed that the birthday celebration—the ritual itself—played a causal role in aging (Woolley and Rhodes 2017).

Rituals are often loaded with symbolic actions, words, and objects, such as placing a ring on a finger, blessing with water, wearing black clothing, or anointing the sick. Rituals, both secular and sacred, also reinforce ideologies, pointing out correct behavior and values in that culture. Ideologies are beliefs about how things should be—how people should think and behave. Marriage vows, for example, might highlight values like fidelity, loyalty, honor, and sometimes even obedience. Wedding rings symbolize fidelity and loyalty and identify a person as married. Graduation ceremonies highlight values like hard work, persistence, and dedication. Moving the tassel from right to left symbolizes your transformation into a college graduate.

Rituals that ensure a transformation from one life stage to another life stage have a special name—rites of passage. A rite of passage can be very simple. In some cultures, naming ceremonies transform an infant into a person. That is, the baby is not recognized as being a full-fledged person until given a name. Baptism transforms someone from a non-member to a member of the church. Marriage transforms a person from an unwed person to a spouse. In some cultures, people are not even considered dead until a rite of passage ritual is performed. In Sulawesi, in eastern Indonesia, people Westerners would consider dead are thought to be just sleeping or sick. The body is kept in the house, given food, talked to, and cared for until the funds for an appropriate funeral can be secured. This continues, sometimes for years, before the funeral. Only after a large and elaborate funeral and appropriate interment is the person considered to have passed on.

Perhaps the most dramatic rites of passage are coming-of-age ceremonies, those rituals that mark the transition from childhood to adulthood. Everywhere, adults and children are treated differently, and rites of passage make it clear which category a person is in and how they are to be treated. Quinceañeras and debutante balls are examples of rites of passage from childhood to womanhood. In some traditional variants of the ritual, the quinceañeras (the initiates) are permitted to start tweezing their eyebrows and wearing makeup. The girl, now a woman, is often given high heels and gives away an item from her childhood like a doll to a younger sister, as a symbol of her transformation. It is not unusual for initiates to be identified through articles of clothing, hairstyles, jewelry, tattoos, or bodily decoration that children are not permitted to wear.

As part of the coming-of-age ceremony, girls are often instructed in the proper way to be a wife and mother. Among the Diné (Navajo) and Apache of the American Southwest, girls may undergo a Kinaalda ceremony, which transforms a girl into a strong and capable woman. In Nigeria, Efik girls who have started menstruation are secluded in a hut, fed to gain weight, and instructed in the proper behavior and beliefs for a wife and mother. Traditionally, the Masai of East Africa have coming-of-age ceremonies intended to transform a carefree girl into a full-grown woman with the responsibilities of womanhood.

The traditional Masai of Tanzania and Kenya coming-of-age ceremony involves female circumcision—also called female genital cutting or female genital mutilation—in which the clitoris is removed with a knife (there are several variations of this practice). Infections and difficulty giving birth are complications of the practice. The practice has been outlawed in Kenya but continues to be practiced by some Masai and in other countries in Africa and the Middle East. Sarah Tenoi (2014), who has been circumcised and prefers the term female circumcision, explains, “the cultural roots of female genital cutting are so embedded in my community that parents believe it is the best thing for their daughters. Girls often want to be circumcised so that they will be fully accepted by their culture.” An estimated half a million women and girls who had undergone genital cutting living in the United States (Wescott 2015). Like the Cofán of the Amazon, who are reconciling traditional and Western ideals and practices, the Masai are working to transform their society on their own terms. Sarah Tenoi proposes an alternate rite of passage that does not involve cutting, and instead pouring milk on the girl’s thighs. In addition, Tenoi (2014) explains how it is important to involve everyone in the community and to encourage Masai warriors to publicly state that they would marry non-circumcised women.

Boys’ coming-of-age ceremonies are often equally intense as girls’. Among the Sateré-Mawé peoples in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest, young men undergo a rigorous coming-of-age ritual. Venomous bullet ants (Paraponera clavata) are sewn into gloves which are then placed on the hands of the initiates. These large ants, around one inch long, inject a neurotoxic venom that has been compared to being shot. I have seen people bit by a single bullet ant in Costa Rica. There was a lot of swearing needless to say along with days of redness at the sting site. When asked about the ceremony, one Sateré-Mawé explains, “If you live your life without suffering anything, without any kind of effort, it won’t be worth anything to you.” And so, the ceremony, like so many things in human society, appears to be a way to create value and meaning for living. Remember in chapter 2, we discussed how meaning is something not seen in other species. In this way, we can view rituals and rites of passage as ways of creating a structure that defines what is valued and meaningful.

Among the Masai, pastoralists of Kenya and Tanzania in east Africa, initiation into warrior-hood traditionally meant killing a lion with nothing but a spear. This proved their bravery and also rid the Masai of predators that kill their cattle. Ritual killing of lions was abolished in Kenya in the 1970s, but the practice persisted. Today, because of the dwindling lion population and economic opportunities that come from eco-tourism, the Masai have rites of passage. In one case, Masai warriors put on a kind of “Masai Olympics,” where one’s prowess is demonstrated by competitive spear throwing. Warriors have also become “wildlife warriors”, finding ways to conserve wildlife while protecting the cattle, the lifeblood of Masai culture.

Western people truly are W.E.I.R.D. because they tend to have very little in the way of coming-of-age rituals. Western milestones tend to be linked to age–getting a driver’s license, reaching the legal age for smoking, watching certain movies, or drinking. There is very little in the way of symbol, ideology, or transformation involved. Given this stark contrast with non-Western societies, the question arises whether we are missing something by lacking coming-of-age rituals. Parent Ron Fritz recognized this lack of ritual and decided to create his own coming-of-age rituals for his children based on ritual, community, values, and challenge. These rituals included running challenges, job interviews, and building an Ikea bookcase. Then adults shared their wisdom with the teens in a circle. Westerners also have personal rituals that are intended to transform through the supernatural. Personal rituals are not shared by an entire community but are particular to a person. Before going on stage, Stephen Colbert would slap his face twice, chew the right side of a Bic pen, and ring a little bell in a bathroom. Somehow these personal rituals provide a feeling of comfort and control for humans, especially before a big game, before a recital, or a big exam. Superstition also affects consumers. Lauren Block and Thomas Kramer found that Taiwanese consumers would pay more for fewer items because the lower number of items was considered lucky. They were also susceptible to buying an item at a higher, but luckier, price. The authors posed, “How much more profit could Taco Bell have earned if they had altered their seven-layer Crunchwrap Supreme into an eight-layer one for Chinese consumers? Similarly, the current $4/$4/$4 (unlucky) promotion by Domino’s Pizza may not be as well received by Chinese consumers as had been hoped by the company (Block and Kramer 2009).” So much for humans being different from other species because of our rationality.

Religious Forms

In forager societies, religious beliefs often take two related forms. Animism means that nature is “animated” or endowed by distinct spirits. Plants, animals, rocks, trees, mountains, the sun and moon, springs, and other geographical features are inhabited by a specific spirit or soul. No distinct line exists between humans, animals, and the environment—all are endowed with a spirit, soul, consciousness, or agency. The idea of an animated universe is quite common, even in non-forager societies. In Ireland, the Celts believed certain trees contained spirits and were central meeting places for tribes. Animistic behavior is also common in modern Western societies. We talk to our cars and computers, and some of us even talk to plants. Children’s books and movies are filled with animistic images of talking trees, animals, and objects.

A similar concept is animatism. In this case, spirits are impersonal, not tied to specific kinds of plants, animals, or objects, and are potentially everywhere. Animatism is a transferable force and is a kind of generalized spirits like luck, charm, spirit, or charisma. Mana of the islands of the South Pacific, a force or energy that inhabits everything to one degree or another, is an example of animatism. The massive shield volcano Haleakalā that forms most of the island of Maui is thought to possess concentrated mana. Some people or things have concentrated mana and can be dangerous to ordinary people. Mana can be inherited as well as acquired or lost through actions. Taboo is a kind of negative mana and can be contaminating. Taboo things, like weaponry or sacred objects, are to be touched only by certain people. Animism and animatism are not inconsistent with other types of religious beliefs. Most people in modern society believe in luck to a certain extent, and many of us carry crystals, amulets, or special heirlooms. If a Masai warrior heard us talking about good luck or bad luck, he might come away thinking we were quite animatistic.

Sometimes the term magic is used to refer to a system of causation that does not adhere to natural causes. Like rituals, magic transforms through the supernatural, but is not necessarily a repetitive practice. The desired outcome could vary greatly, from attracting a mate to causing harm. Usually, special incantations, behaviors, and treatment of objects accompany magic. The term sympathetic or imitative magic was outlined by anthropologist James Frazer (1854–1941) in The Golden Bough. One form of sympathetic or imitative magic imitates the desired outcome and works on the principle of similarity, essentially “like produces like.” For example, during the ice age, hunters painted scenes of animals with spears flying at them. This is thought to be an example of hunting magic, where the image supernaturally ensures a successful hunt. This is not so different from modern-day manifesting, where visualizing an event happening produces the event. Another example comes from my childhood. If you gave a wallet or purse to someone, it had to include a coin in one of the pockets. This would ensure that the wallet or purse would always have money. On New Year’s Eve in Ecuador, people run around the block with empty suitcases to ensure that they will travel a lot in the coming year. The burning of effigies at the New Year, like Zozobra in New Mexico or politicians in Latin America, ensures that the negativity associated with them won’t affect the new year. In Bolivia, there is a festival called Alacitas where people buy replicas of the things they want for the New Year, such as houses, cars, baby dolls, chickens (to find a partner), miniature tiny cameras, computers, fake money, and passports. These are then offered to Ekeko, the god of abundance. A voodoo doll is another good example of sympathetic magic. The doll and the victim are connected through their similarity. Among the Hmong of Laos, women having difficulty getting pregnant will consult a healer, who ties a string from the door to marriage bed, such that the baby’s soul can find their way to the mother’s womb (Fadiman, 1997). For an especially difficult labor, a woman could drink water boiled with a key, so as to unlock the birth canal (Fadiman, 1997: 15).

Contemporary Voodoo Doll with 58 pins by is licensed under CC BY SA 3.0

Contemporary Voodoo Doll with 58 pins by is licensed under CC BY SA 3.0

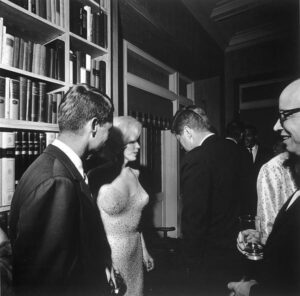

Another variety of magic introduced by Frazer is magical contagion. In this kind of magic if something comes in contact with another object it can leave behind some of its essence or can act on the object at a distance. This is not very different from the concept of animatism. For instance, one student described how after he shaved his head, his grandmother would make him collect his hair and burn it, just in case a witch might want to use it against him. This magic is also present in voodoo dolls, if the hair, for example, of the intended victim, is attached to the doll. In some cultures, personal items are endowed with the essence of people and are symbolically killed or destroyed upon death to release that essence. Sometimes the effect of magical contagion is positive. For instance, as a child, a student thought that putting glitter on pictures would make them come to life. Objects can have qualities of magical contagion, especially those touched by someone famous or infamous—a kind of real-life Horcrux. Autographs work like this–it’s like celebrities and sports heroes leave a little piece of themselves on the paper. Some people convert their deceased pet’s collar, fur, or cremated bones into jewelry that they wear. It’s a way of keeping the essence of their pet close to them. The same is true for objects closely associated with famous people. Psychologist Bruce Hood likes to ask audiences if anyone is willing to try on a serial killer’s sweater for money. Very few people accept the offer to wear “the killer cardigan”, demonstrating that many people have underlying magical or animistic/animatistic beliefs. In 2016, one of Marilyn Monroe’s dresses (the “Happy Birthday Mr. President” one) sold for more than 4 million dollars (Juto 2016). It originally cost about $1500. A good example from New Mexico is the healing Chimayo earth which is said to have miraculous properties. When a friend of mine was a child, his mother brought him to the Chimayo chapel because he was “blinking too much.” His mother threw a handful of the healing dirt into his face and after that his excessive blinking disappeared.

There are many examples of magical contagion in sports. In his book, Alter Ego performance coach Todd Herman describes how he would place trading cards of professional football players on his shoulder pads to improve his game. This is also a bit like imitative magic because the cards themselves are imitating the players! A student once did something similar by getting tattoos of the Icelandic staves Gapaldur and Ginfaxi; historically these symbols were placed in the shoes to ensure victory. One of the best examples of both magical contagion and imitative magic comes from a former student. The student explained that mixed martial arts champion would always wear a lucky sweater to insure a successful fight (magical contagion). Another fighter then imitated him by wearing the same sweater (imitative magic)!

Shaman are typically part-time healers who communicate the needs of the living with the spirit world. Sometimes shaman help others make the journey. Shaman often accomplish this with rituals, trances, ritual drumming, singing, or sometimes hallucinogenic drugs. Ethnobotanist Terrance McKenna explains that “shamanism is about going into the realms of death, transcending the body, transcending space and time…What the psychedelics do is that they dissolve boundaries. They dissolve the illusion of separateness” (Shamans of the Amazon 2016). One well-known plant from the Amazon is ayahuasca which is called the “vine of the dead”. When coupled with another plant, Psychotria viridis, which contains DMT (dimethyltryptamine), it produces powerful hallucinogenic effects.

In contrast to animism, theism means belief in supreme deities, where gods rank higher than humans. Polytheism means many powerful gods and goddesses or deities. Ancient Egyptians, Mayan, Hindus, Greeks, and Romans are all good examples. Very typically, the human ruler in polytheistic societies was also divine or semi-divine. In polytheistic religions, powerful gods and goddesses needed to be appeased through sacrifice and rituals to remain benevolent and to ensure a good harvest and health. Polytheism is associated with more complex, hierarchical societies. The ancient Hebrews were an exception, being monotheistic— with the single powerful god Yahweh.

Communitas and Collective Effervescence

When I was in Rome and saw the Pope, there was electricity in the air and I was swept up in the moment. French sociologist Emile Durkheim called the intense feeling of togetherness and ecstatic excitement that accompanies ritual “collective effervescence”. Religious activity such as prayer, meditation, chanting, dancing, and singing has a measurable physiological effect on people. The field that studies this phenomenon is called Neurotheology. Brain scans (FMRI) show decreased blood flow in certain areas (parietal lobe) of subjects engaged in spiritual practice, perhaps relating to a decreased sense of self. Long-term meditation results in thickening in the cortex of the brain associated with attention and sensory processing. Speaking in tongues results in decreased activity in the frontal lobe. This squares with what people say they experience, that is, being outside of themselves and overcome by some outside force. Some people might even have spiritual experiences in other non-religious endeavors like painting, singing, sporting events or other activities not related to the supernatural. We see this on social media in flash mobs. Where people start spontaneously singing and dancing, and everyone stops and participates in the moment as if time has time itself has stopped. Even if one does not feel “outside of themselves” or part of something larger, many people feel a senese of communitas when engaging in group activities like making music together, dancing, or playing a sport. One student provided a great example of this that they observed at the Waterpark Village Vacances Valcartier in Quebec. The park has a waterslide where a single person is locked in a chamber, then the floor suddenly drops away, and the person rockets straight downward into a waterslide tube. The intenseness of the experience has a pronounced effect on people. Strangers begin to chat and offer encouragement (You got this!) and offer advise (Fold your arms in front!”) to the “initiate” who is about to disappear into the unknown before their eyes. The normal rules of social engagement are suspended and people who would normally ignore each other are comming together with a sense of communitas and oneness. It may be that human rituals tend to be intense precisely because they inspire intense feelings of unity and sometimes “effervescence.”

When Did Belief in the Supernatural Begin?

Supernatural beliefs themselves cannot be discovered in the archaeological record, being by definition “beyond the natural”. Archaeologists only have the material record to work with. Religious texts can be very informative, but the invention of writing only began around 5,500 years ago in Mesopotamia. What then can archaeologists use to infer that people had a belief in an unseen order or rituals associated with religious belief?

The first evidence for supernatural beliefs are much older than religious texts, going back tens of thousands of years into the Pleistocene or the ice ages. At Lascaux Cave in France, there are some 2,000 paintings that are about 17,000 years old. The figures are depictions of ice-age animals, especially horses (very similar in form to the threatened Przewalski’s Horse). There is little evidence that ice-age people lived in the interiors of these painted caves, but went to great lengths to paint them. This has led archaeologists to speculate that the images were not art for art’s sake but rather related to shared religious beliefs and perhaps used in the course of religious rituals. Archaeologist and priest Abbe Henri Breuil (1877–1961) suggested that ancient paintings of animals on the walls of European caves were a form of sympathetic hunting magic, an attempt to increase animal numbers or aid in the hunt through the concept of “like produces like”. In essence, depicting the animals with spears in them assists in the actual hunt.

At the site of Dolní Věstonice in the Czech Republic (circa 27,000 years ago), archaeologists found a small structure located away from a village. The structure contained a specialized oven or kiln for firing ceramics. Approximately 2,300 loess (fine silt) figurines depicting lions, foxes, bears, horses, and rhinos were discovered, along with more than 2,000 loess balls. Most of the figurines were broken and archaeologists determined that they were intentionally destroyed during firing, perhaps as part of a ritual performance. Archaeologists speculate this was an early shaman’s hut.

But perhaps the most obvious indicator of supernatural beliefs are burials, especially those burials that contain grave goods. An early example of a human burial comes from Sungir in Russia. At Sungir, burials include one adult male and two children, who are buried head-to-head. The site dates to ca. 24,000 years ago, and the three burials included more than ten thousand ivory beads, mammoth ivory bracelets, beaded caps, decorated belts, ivory pendants, an ivory lance made from a straightened wooly mammoth tusk, and an animal pedant among other grave goods. The intentional burial of human bodies with objects suggests that people even tens of thousands of years ago had some concept of the afterlife.

Everyday Unseen Orders

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz was not happy with the definition of religion as being about the supernatural. Rather, he focused on ideas about the “order of existence”—how the world is and how it should be. For Geertz, these worldviews are supported by symbols, made to seem natural and obvious, and can be highly motivating. Geertz’s definition of religion doesn’t involve the supernatural at all.

Similarly, others have pointed out that humans have created their own “unseen orders” that we interact with daily. We live in a material world, but we also live in a world of our own making. Historian Yuval Harari points out that humans accept all sorts of ideas that cannot be measured or even seen, but rather are purely abstract concepts and values that we have invented that we take for granted as normal and obvious. For example, we accept the existence of nations and laws as if they truly existed in the material world and not concepts created by humans. The ideas of nations are supported by symbols like the Statue of Liberty and the American flag and rituals like saying the pledge of allegiance or singing the national anthem. Flags are not merely colorful pieces of cloth, and people have strong opinions about how the American flag should be treated. Indeed, the Flag Code embodies a supernatural and starkly animistic idea stating: “The flag represents a living country and is itself considered a living thing.” When the symbols and rituals of these unseen orders are disrupted or questioned—by the tearing down of monuments or kneeling during the anthem—many people have very strong reactions. In this regard, everyday institutions like schools, companies, and nations, are not so different from religions having their own ideologies, rituals, symbols, and sometimes even supernatural beliefs.