The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 12: Statehood Achieved & Loyalty Questioned: the World War I Era

- Statehood Achieved & Loyalty Questioned: the World War I Era

- Statehood Finally Arrives

- "Loyalty Questioned": Revolution & War

- References & Further Reading

As the final stages of the statehood battle made their ways through Washington D.C. channels, revolution erupted in Mexico. From exile in San Antonio, Texas, hacendado (large landholder) Francisco I. Madero led opposition to the continuance of the Porfiriato (the name for President Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship which began in 1876). Madero’s Plan de San Luís Potosí called for the initiation of revolution against the aging dictator on November 20, 1910. By early 1911 battles between revolutionary forces and Mexican federales regularly occurred along the border with the United States.

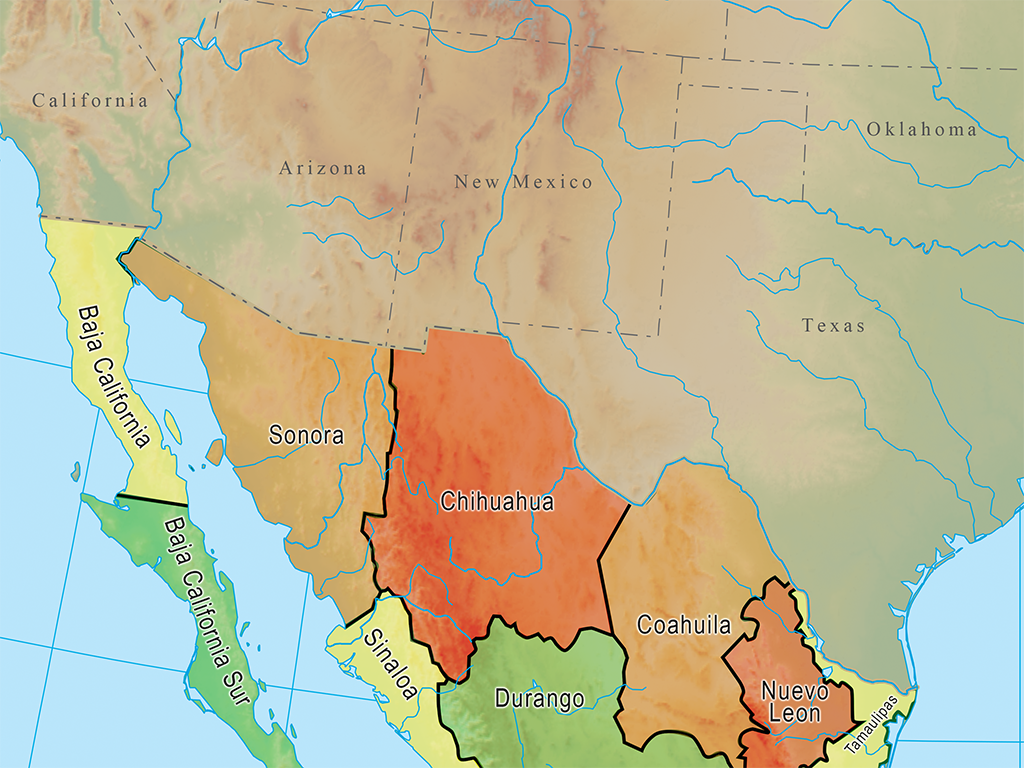

Part of the reason for the revolution’s concentration along the international border was that the states of Chihuahua, Sonora, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas had been impacted most directly by U.S. investment and economic control. Peasants lost their communal rights to land and vital resources as the Díaz administration made concession after concession to foreign enterprises in an effort to bring Mexico into the modern, capitalist world. Indeed, the pattern of modernization in Mexico began with the liberal reforms of the 1850s that resulted in the adoption of that nation’s Constitution of 1857. By the early 1900s the stress that modernization placed on Mexican peasants and indigenous peoples had pushed them to the breaking point.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

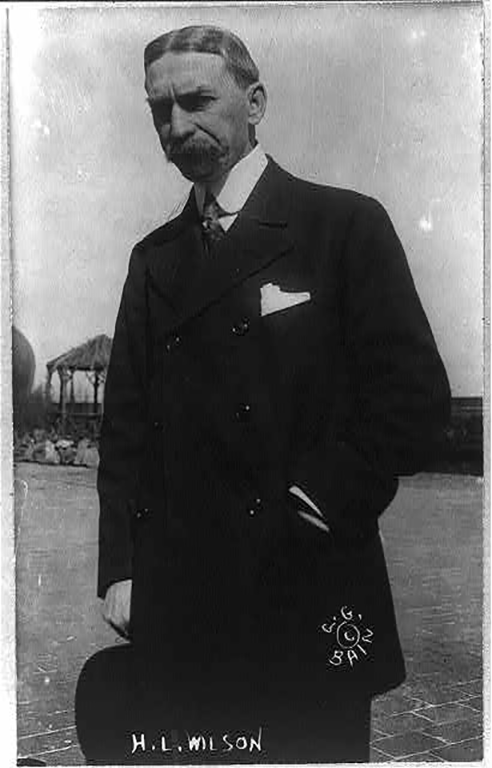

Wealthy and middle-class Americans initially considered the revolution to be something of a spectator sport. In one iconic photo, Anglo-Americans congregated at the top of an El Paso hotel to get a view of the civil war that was taking place just across the Rio Grande in Ciudad Juárez. The April 1911 Battle of Ciudad Juárez was a major defeat for the forces of Porfirio Díaz and he shortly thereafter fled into exile. Despite hopes that the Madero’s government would restore order and create balance for Mexico, such was not the case. Madero and his vice president, José María Pino Suárez, were assassinated in February 1913 by reactionary forces who had the support of U.S. Ambassador, Henry Lane Wilson.

Just prior to the assassination, editors of the Las Cruces Citizen noted, “Even El Pasoans are becoming nauseated with what they once considered so amusing.”17 The violence of the Mexican Revolution potentially ran counter to the message that New Mexican boosters wished to project: that the new state presented a prime opportunity for settlers to establish family farms in the Southwest. For example, promoters in Columbus claimed that their small, dusty border town might one day exceed El Paso as the principal port of entry between the United States and Mexico.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Such was never to be the case, but the dreams of Columbus boosters illustrate the ongoing tensions between the hopes of statehood and the desire to maintain trade with Mexico. New Mexico Senator Albert B. Fall, as one example, possessed vast interests in Mexico. Unlike other Americans, he was in the unique position to petition the U.S government to take action to protect his Mexican holdings in the face of the revolution. Fall issued countless petitions and conducted a public series of hearings in 1920 to protect his investments.

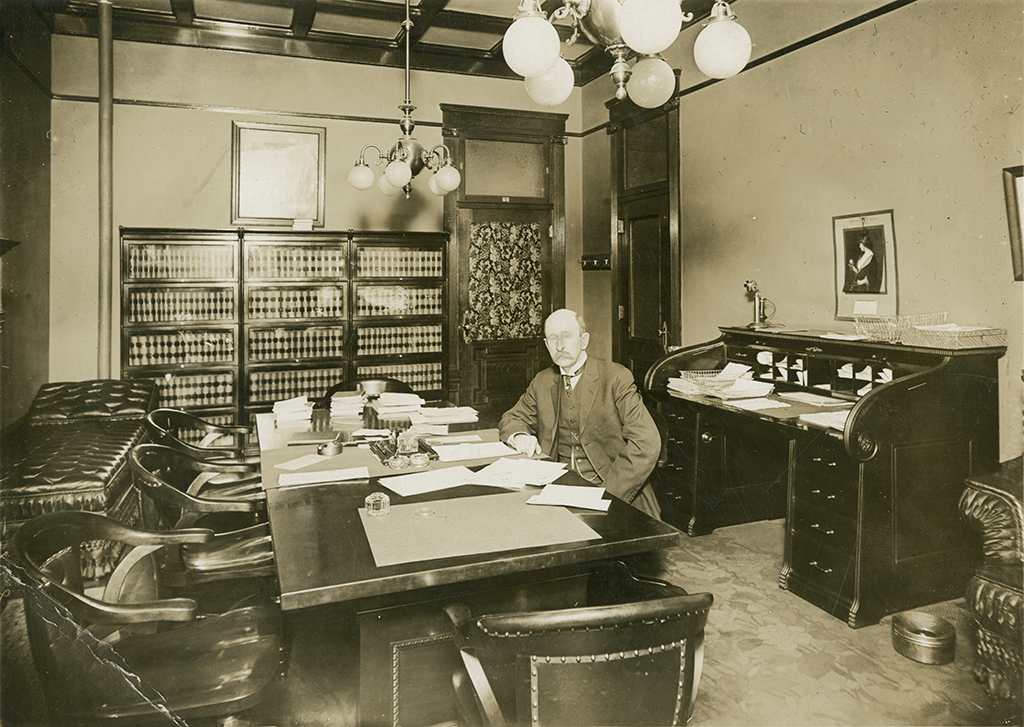

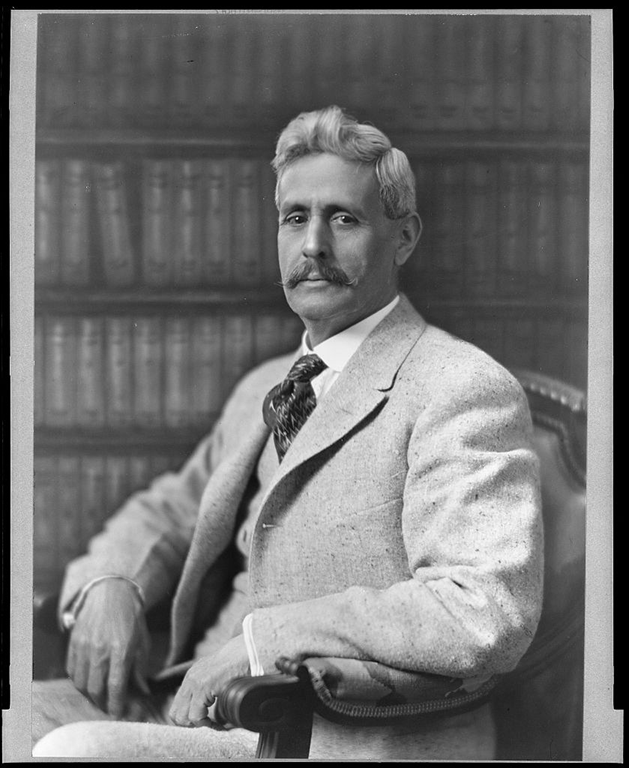

McDonald served as governor between 1912 and 1917. During the Mexican Revolution, residents in the southern section of the state petitioned him for arms and reinforcements to protect against potential violence. This photograph shows him in in his State Capitol office, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 152652.

In contrast with the senator’s position, which was geared toward protecting economic gains, other New Mexicans understood their relationship with Mexico during the decade of the 1910s on social, rather than economic, terms. In 1914, residents of Rodeo, New Mexico—a tiny community in the state’s “boot heel,” petitioned Governor William C. McDonald for troops and arms to guarantee protection from Mexican revolutionary violence. The small community was concerned not only that revolutionaries might cross the border to wreak havoc on their town, but also feared “the Mexicans at and around the Mining Camps in Arizona northwest of us that might want to return to Mexico and would probably take this route on account of it being rough and unsettled, and that they would rob and murder on their way, not only for revenge but also to get outfits together.”18

Ironically, in 1913 and 1914 residents of southern New Mexico looked to General Pancho Villa as the revolutionary leader who could restore order along the border and in Mexico generally. Even President Woodrow Wilson believed that Villa could be the best hope for American-style democracy in Mexico. During 1913, Villa’s success gained him control of the state of Chihuahua, and he briefly served as its governor.

During the general’s dominion over Chihuahua, Villa kept an office in Columbus. Although it is unclear how often he visited the office, the presence of his officers there seemed to provide many Columbus residents with a sense of calm in the middle of the revolutionary storm. As Daniel J. “Buck” Chadborn recalled, “To show how cooperative Villa was, he gave me a safe conduct pass for my protection though I didn’t ask for it. It was presented to me in Villa’s Columbus office by two of his right-hand men, Leoncio J. Figueroa and Antonio Moreno.”19 Chadborn’s work as a line rider for the U.S. Customs Service, as well as his personal interest in a local cattle enterprise, meant that the gesture was important for building peaceful border relations between villista forces at Palomas and citizens of Columbus.

In August of 1914, Villa himself passed through southern New Mexico with his erstwhile ally General Alvaro Obregón. After meeting with General John J. Pershing at Fort Bliss in El Paso, the rail entourage proceeded along the Southern Pacific en route to Sonora, where Villa and Obregón were to meet with Governor José María Maytorena. The group stopped in Deming for breakfast on the morning of August 27 and residents of the town rushed to see Villa. In accordance with his established tactic of constantly working to build his own reputation, Villa addressed the crowd in Spanish from the deck of his private railcar. He assured the New Mexicans that the violence in Mexico would soon come to an end, and he made a direct appeal to the community’s Mexican residents, most of whom lived in a section of town called “Little Chihuahua.” Villa told them that he wanted “to see the Mexican people united in one solid nation, living in peace and happiness,” and that he forgave any who had formerly been his enemies. He invited them to return to Mexico where he would treat them as members of his own family.20

The Robert Runyon Photograph Collection [00196], The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

Less than two years later, Villa’s forces were decimated by Obregón’s use of modern war tactics that were also employed in World War I, such as barbed wire, trenches, and machine guns. Villa failed to adjust his battle tactics accordingly, and by the spring of 1916 was in a desperate struggle to maintain a semblance of his former fame and reputation on the battlefield.

Historians have debated the various reasons for which Villa decided to raid Columbus on March 9, 1916. Although there is no agreement on the particulars, most scholars believe that Villa’s main goal was to provoke a U.S. military expedition into Mexico. From that perspective, Villa gained his objective. Over the next two years, willing recruits joined his forces to fight against Pershing’s Punitive Expedition and in reaction to the notion that the opposing revolutionary forces led by self-proclaimed First Chief Venustiano Carranza had sold Mexico out to the United States in economic and political terms.

The story from the perspective of Columbus residents, New Mexicans, and Americans was quite different. The central business district of the small town lay in shambles, as did the lives of most of its inhabitants. Episodes of violence, loss, and heroism emerged during the battle. William T. Ritchie, who operated the Commercial Hotel with his wife Laura, refused to back down when a group of villistas stormed into the hotel. After attempting to protect his wife and girls, the soldiers forced him out onto the street where he was gunned down along with several other male guests.

Archibald Frost, who operated a furniture store in town, was gravely wounded as he attempted to escape the center of town with his wife and newborn son. On the bumpy road between Columbus and Deming, Mary Alice took the wheel from her husband because he was unable to drive due to bullet wounds. The family arrived at Deming where they received medical attention and recovered.

Nineteen-year-old telephone operator Susan Parks hunkered down at the switchboard and called military officials at Fort Bliss to inform them of the attack as it was in progress. She hid her baby girl, Gwen, under the bed in an attempt to keep her quiet because a group of villistas stood across the street.

Courtesy of TonyZ/U.S. War Department

Lieutenants John P. Lucas, James P. Castelman, and Colonel Frank Tompkins led the charge that forced the villistas to end the raid and retreat across the border into Chihuahua. Lucas and Castleman organized other soldiers in the Thirteenth Cavalry behind machine guns in town, and Tompkins pursued retreating villistas into Chihuahua as they fled. Villa himself lived, although nearly one hundred of the men he had forced into service perished.

In the months following the raid, Columbus ballooned in size due to the near-constant arrival of National Guard units from across the United States to support the Punitive Expedition that had entered Chihuahua in mid-March. Columbus was the expedition’s supply base, and General Pershing established his headquarters near the Mormon town of Colonia Dublán, Chihuahua.

Mexican President Venustiano Carranza could not prevent the Punitive Expedition from entering his nation. Despite Woodrow Wilson’s reassurance that Mexico’s sovereignty would be honored, Carranza found himself in an untenable position. In order to publicly refute Villa’s unfounded accusation that he was in collusion with the United States, Carranza refused to support the Pershing expedition. Throughout the expedition time spent in Chihuahua between March 1916 and early February 1917, Carranza’s forces actively opposed U.S. forces, most notably at the battle of Carrizal in southern Chihuahua in June 1916.

The Punitive Expedition illustrated the U.S. Army’s state of unpreparedness for a sustained campaign. Despite the relatively rapid amassment of supplies and men in Columbus, the military did not possess enough trucks to transport the needed ammunition, food, and other items to the Colonia Dublán headquarters. Regular cavalry and infantry units were supplemented with National Guard contingents that were often insufficiently trained for reconnaissance and combat missions.

General Pershing directed efforts to correct the problems endured during the Punitive Expedition. Although U.S. forces failed to capture Pancho Villa, they field tested new technologies such as tanks and Curtis JN-4 biplanes, known as “Jennies.” The planes allowed surveillance from the air that had not been imaginable in prior conflicts, but the Jennies had difficulty gaining enough altitude to traverse the mountainous regions of western Chihuahua.

Support was enthusiastic for the hunt for Pancho Villa, but the loyalties of nuevomexicanos remained suspect to many Anglo Americans. The idea that New Mexico’s hispano population more closely related with the Mexican nation than the United States had not completely abated, despite statehood a few years earlier. Also, the very public efforts of some New Mexican attorneys to represent Mexican revolutionaries accused of breaking neutrality laws did little to help matters. Elfego Baca, for example, represented Mexican General José Inez Salazar, accused of breaking neutrality laws by retreating across the border into south Texas to avoid an attack by villista forces in 1913. Baca allegedly participated in Salazar’s escape from an Albuquerque jail. Despite never being convicted on the allegations, Baca was disbarred for his efforts to evade the investigation into his actions.

Nuevomexicanos refuted claims of their disloyalty in rallies in the state’s cities and towns. They emphasized the reality that the state’s National Guard units that aided the Punitive Expedition were comprised of hispanos. At a rally in Santa Fe, local nuevomexicanos chastised the national press for promoting prejudice “in the minds of the unadvised and thoughtless against a large proportion of our people who are not of the so-called Anglo Saxon descent.”21 As scholars argued by Phillip Gonzales and Ann Massmann, “In truth, the border hostilities heightened nuevomexicanos’ loyalty to the United States.”22

Interestingly, while much of the nation was engulfed in calls for “100 percent Americanism” and the end of “hyphenism” (i.e., the visual and vocalized methods of group identification that emphasized an ethnic group’s origins, such as the term “Spanish-American”), nuevomexicanos found that the World War I era provided them the opportunity to show their loyalty to the United States without abandoning their ethnic identification. Nuevomexicanos’ experiences at war and on the homefront during the Great War (as World War I was known prior to the Second World War) illustrate the harsh reality that the issue of full inclusion in the Union had not been resolved by statehood.

William H. Roberts (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 149995.

Like Americans across the nation, nuevomexicanos answered the call to service and sacrifice. They intensified their cultural sensibilities even as they did so. Once again, the Spanish-language press in New Mexico led the way in expressing the connections between nuevomexicano culture and American loyalty. Newspapers like La Voz del Pueblo published poetry in Spanish that emphasized elements of nuevomexicanos’ Iberian heritage, and that were geared to inspire honorable service during the conflict.

Additionally, a cartoon image created by Jesuasa Alfau, an artist born in Madrid who lived in New York City during the second decade of the twentieth century, resonated with New Mexico’s people. Alfau’s drawing presented Queen Isabella giving her jewels to a portrayal of Columbia, a female personification of the United States. The image, published in the national and New Mexico press with Spanish captions, reminded its viewers that Spain had been responsible for European arrival in the Americas. By extension, it accentuated the idea that those who claimed Spanish blood could both emphasize their unique cultural heritage and their loyalty to the United States in a time of war.

In stark contrast to earlier accusations levied by Senator Albert J. Beveridge, during the war New Mexico’s Spanish-language press was recognized for its dedication to the American war effort. Nearly every hispano community in the northern part of the state boasted a Spanish-language weekly. Some examples included La Voz del Pueblo (Las Vegas), La Revista de Taos, Albuquerque Bandera Americana, and the Las Cruces Estrella. Other papers, like the Deming Graphic and the Santa Fe New Mexican were bilingual.

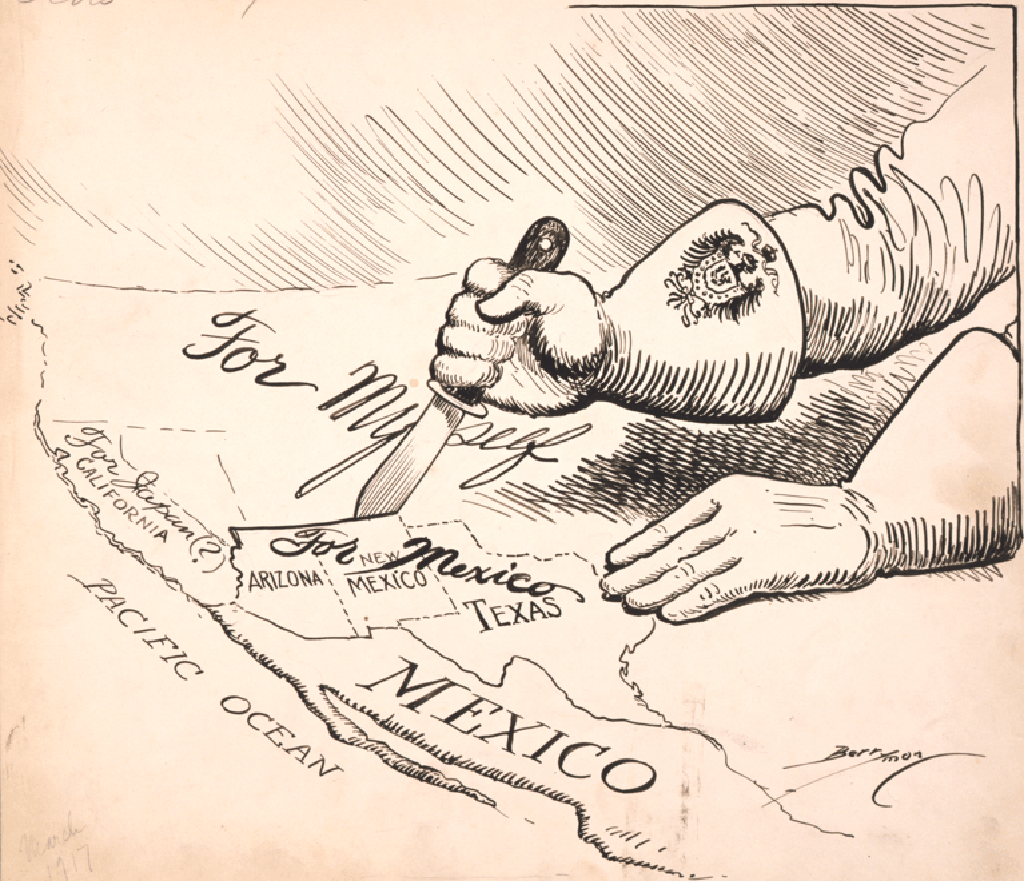

The importance of the Spanish language press on the issue of nuevomexicanos’ loyalty is illustrated in responses to the Zimmermann Telegram just prior to the U.S. declaration of war against Germany in February of 1917. The telegram was an intercepted communication between German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann and the German Minister to Mexico, Heinrich von Eckhardt. British intelligence agents decoded the message, which was a call for Mexico to join the Great War as a German ally. In exchange for Mexican support German envoys promised to help the Mexican government recapture the American Southwest, which had been transferred to the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The Zimmermann Telegram heightened tensions in the United States, and placed intensified scrutiny on hispanos in California, New Mexico, and Texas. The telegram helped generate popular support for U.S. involvement in the European conflict, and the press in New Mexico mocked Zimmermann’s message. José Jordi, editor of La Voz del Pueblo and a recent immigrant from Spain, charged that the proposal was flatly crazy. The passing of time has substantiated Jordi’s comments that, “the biggest proof of their dementia is to think that . . . President Carranza would attempt the reconquest of the Southern United States.”23

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Jordi continued by reaffirming New Mexican support for President Wilson’s move toward committing U.S. forces to the Great War. In reports written in Spanish, the nuevomexicano press worked to enforce complete loyalty to the American war effort, even as it also emphasized the continued value of nuevomexicano use of the Spanish language and the reaffirmation of their traditions and customs.

In their research on nuevomexicano support for World War I, Gonzales and Massmann argue that “cultural citizenship,” or a type of citizenship that emphasized a unique ethnic background and loyalty to the United States, solidified in New Mexico. Collective actions, such as rallies and community gatherings to express solidarity with the war effort, marked nuevomexicanos’ assertions of cultural citizenship. At the Spanish American Normal School (today’s Northern New Mexico College) students dressed in military attire and sung patriotic songs in Spanish. In Taos, L. Pascuál Martínez, editor of the Taos Valley News and El Crepúsculo, led a Decoration Day (the precursor to Memorial Day) rally in support of U.S. participation in the Great War.

Nuevomexicanas manifested support of the war by advocating for women’s suffrage. Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren, one of the leading figures of New Mexico’s hispana literary scene, was identified by Alice Paul, leader of the Congressional Union (CU)—a national women’ suffrage organization, as a key figure who could promote New Mexican women. In 1917, Otero-Warren took the helm of the New Mexico chapter of the CU. Otero-Warren and other notable members of the nuevomexicana elite, including Aurora Lucero, lobbied state legislators for women’s right to vote at the close of the nineteen-teens.

For women, in New Mexico and elsewhere, support of war loyalty campaigns was a means of also fighting for the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Having passed through Congress in 1919, the amendment that granted women the right to vote could not be added to the Constitution until the requisite three-fourths of states had ratified it. Women’s groups, like the one headed by Otero-Warren, played instrumental roles in securing the amendment’s ratification. At the national level, women’s suffrage leaders encouraged nuevomexicanas to support the war effort as a means of also promoting their own cause.

The movement for women’s suffrage in New Mexico was not controlled by national interests. Along with Otero-Warren, who also headed the auxiliary of the First Judicial District and chaired the state-level Red Cross, other women joined the battle for the right to vote. Across the state, they contributed their efforts to simultaneously illustrate their loyalty to the United States and their dedication to the idea of political equality.

Unfortunately, during this time period newspapers and other sources of information identified women in conjunction with their husbands rather than reporting their own names. Accordingly, “Mrs. J. M. Díaz” was listed as the woman who led efforts to produce food, plant victory gardens, and collect Liberty Bonds among northern New Mexicans. In Taos County, Juanita G. Mares and Juanita Saavedra de Martínez headed efforts to collect Liberty Bonds. Women field agents, including Gertrudes Espinoza, served as experts on the preservation of meats, fruits, and vegetables. As we will see in Chapter 13, most of the field agents assigned to rural New Mexico in the World War I era were Anglo American, and their biases shaped the types of reforms that were recommended and eventually carried out under New Deal agencies.

Following the war, Otero-Warren’s experiences put her in a unique position to influence the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in New Mexico. According to Gonzales and Massmann, she “single-handedly convinced wavering U.S. Congressman William Walton to support woman suffrage, and she successfully pressured the Hispanic members of the state house of representatives to vote in favor of it.”24 Other women’s rights advocates, principally those connected to Otero-Warren’s Republican political circles, also petitioned the New Mexico legislature.

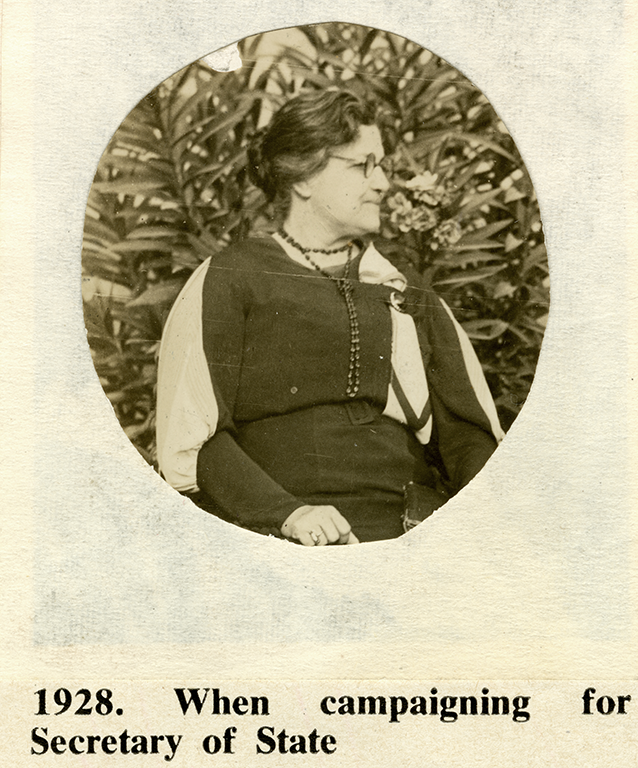

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Governor Octaviano Larrazolo called a special session to consider ratification in 1920. At the end of that session, New Mexico became the thirty-second state to support the Nineteenth Amendment. Nuevomexicanas took advantage of the new political rights that came with voting, and lobbied subsequent legislative sessions in 1921 that opened the way for women to hold office. Otero-Warren narrowly lost her bid for Congress in 1921, but several other women successfully campaigned for state-level positions, principally as secretary of state. Several women held that post during the 1920s and 1930s, including Soledád Chávez de Chacón, Jesusita Perrault and Marguerite Baca.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. HP.2010.42.2.

During the short period of U.S. involvement in the war, Governor Larrazolo had emerged in New Mexico as a symbol of resistance to the racist notion that disloyalty and treason ran rampant in the state. New Mexican legislators debated whether or not to petition for a segregated nuevomexicano unit as young men went off to service, both through volunteerism and the conscription required by the Selective Service Act of 1917.

To some, including Benigno Hernández, a native of Rio Arriba County and member of the wartime New Mexico Council of Defense, the fact that conscription far exceeded volunteer service among nuevomexicanos indicated their ignorance and lack of patriotism. Hernández added the caveat that local hispanos were strong citizens, “when [they] understand things, but those living in the remote villages, or upon stock ranches, have not the reading matter at hand.”25 Taking the accusations much further, a letter published in the North American Review claimed that a treasonous conspiracy against the United States was in motion in New Mexico. The populace’s continued use of Spanish was the supposed evidence for the alleged plot, and the letter’s author claimed that the Penitente brotherhood was a secret society that dictated political, economic and social affairs in New Mexico.

In response to such sentiment, New Mexicans staged demonstrations in Albuquerque and Las Cruces, and members of the state’s congressional delegation, including Albert B. Fall, demanded the letter’s retraction. In the state legislature, Larrazolo, then speaking as a prominent Las Vegas lawyer, argued that a separate regiment for nuevomexicanos was necessary that segregated units would provide comfort to New Mexican servicemen. Hernández also supported the separate regiments, but on the grounds that nuevomexicano young men were not sufficiently assimilated into American culture to thrive in integrated units.

Ultimately, policymakers decided that the proposed separate regiments took the concept of cultural citizenship too far. President Wilson and Secretary of War Newton Baker promised to provide special sensitivity to nuevomexicanos in the service, and many nuevomexicano newspaper editors responded with gratitude. In addition, some, like editor L. Pascual Martínez, continued to advocate for cultural citizenship on the home front. He specifically argued that the federal government also support state-level improvements in educational and economic opportunities.

As New Mexico looked toward the new decade in 1920, the achievement of statehood after a hard-fought, sixty-four year struggle gave its residents a certain sense of accomplishment. Although the implication was that entry into the Union would bring full U.S. citizenship rights to the state’s hispano, indigenous, African American, and Asian residents, such was not the case. Pancho Villa’s raid on Columbus and U.S. participation in World War I proved to many nuevomexicanos that such hopes were in vain. Within a decade of statehood, perceptions of New Mexico’s people as ignorant, backward, and un-American persisted in many sectors of the nation.

The statehood struggle, Punitive Expedition, and World War I underscored the crucial role of political participation. During the war, nuevomexicanas successfully advocated for suffrage and shortly thereafter achieved the right to serve in public office. Hispano politicians also maintained a strong role in state politics as advocates for the rights of New Mexicans. Governor Octaviano Larrazolo was one of many “native sons” to whom New Mexicans appealed when they felt that their citizenship rights had not been properly protected.

During the 1920s, problems of poverty and insufficient educational resources continued in New Mexico to the extent that some observers suggested that residents of the state were not impacted by the economic collapse in 1929. Such claims were based on the idea that poverty was an accepted cultural way of life for the supposedly pre-industrial peoples of New Mexico. Paradoxically, members of the famed artist colonies of Taos and Santa Fe, as well as rural reformers, simultaneously promoted the idea of New Mexico’s peoples as embodying the notions of purity and simplicity that could cure the ills of the modern age, and also as peoples in need of modern models of efficiency. Their perceptions of New Mexico furthered the incorrect notion that the Great Depression did not greatly impact the state’s people, but the New Deal provided artists and reformers with resources they needed to record, preserve, and reproduce cultural goods among Pueblos, Navajos, and hispanos. The Depression era will be addressed in the next chapter.