The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 15: Civil Rights Movements

- Civil Rights Movements

- Alianza de Mercedes Libres

- Chicano Community Organization

- African American Rights

- Indigenous Peoples' Civil Rights

- References & Further Reading

As in the case of African American civil rights in New Mexico, Native Americans utilized the legal system to assert their rights to equal treatment before the law. Also, as was the case for Chicanos, access to land and resources lay at the center of Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache civil rights activism in the period between 1950 and 1970. Most of New Mexico’s Native Americans did not participate in the more militant manifestations of the civil rights era, such as the Red Power movement or the American Indian Movement (AIM), but they used other methods to advocate for equal treatment before the law and status as U.S. citizens.

As historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has argued, during the Civil Rights Era “Pueblos stuck to their method of defending their rights, making considerable gains, such as the return of Taos’s sacred Blue Lake.”25 For centuries, since the Spanish Reconquest of New Mexico, most Pueblo people preferred to work within current legal and political systems to preserve their right to lands, resources, and cultural identity. Their ability to do so should not be underestimated: they have endured three colonial impositions under Spanish, Mexican, and then U.S. administration.

Courtesy of Indian Pueblo Cultural Center

In the 1920s, Pueblo peoples re-established the All Indian Pueblo Council (AIPC) to defend their lands and access to crucial resources like water and timber. Their efforts in the early twentieth century resulted in the 1924 Pueblo Lands Act. Interestingly, John Collier participated as a field worker in the battle to achieve passage of that legislation, an act that propelled him to the position of BIA director in the Roosevelt administration.

Pueblo concerns of the 1920s and the Depression era did not abate following World War II. As was the case with many nuevomexicano villages, Pueblos faced depopulation due to the increasing need to relocate to towns and cities that offered more employment opportunities than could be found within Pueblos themselves. Also, as was noted in Chapter 14, atomic developments in New Mexico appropriated Native peoples’ lands and resources—in the form of land for Los Alamos National Laboratories (LANL) and for the extraction of uranium.

As people moved away from nuevomexicano villages and Pueblo towns, tax revenues decreased resulting in lower funding for education and health care. Due to such developments, Dunbar-Ortiz concluded that “northern New Mexico had been brought into the mainstream of the American economic system and it resembled other depressed rural areas of the United States—parts of the Deep South and Appalachia, for example.”26 In furthering this perspective, Dunbar-Ortiz highlights the continued legacies of colonialism in New Mexico.

The AIPC successfully advocated for the return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo in 1971, but their achievement was hard fought. Several witnesses who testified before the Senate Subcommittee worried that the return of Blue Lake would set a “dangerous precedent.”27 Senators finally reached the conclusion that the Taos case was sufficiently unusual to bar the creation of a precedent, and the measure succeeded.

Under the terms of an executive order signed by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906 that designated the area as part of the Carson National Forest, Taos Pueblo had lost all rights to Blue Lake. As soon as the order was issued, Pueblo leadership initiated a legal battle to regain rights over the sacred landscape.

Although opponents argued that Taos Pueblo had no legal claim on Blue Lake, the Taos Pueblo Council referenced the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo as evidence of their centuries’ old legal right to the area. The treaty guaranteed land titles from the Spanish and Mexican eras. In a 1955 press release, the council cited a passage from the Recopilación de las Leyes de las Indias as evidence that the Spanish Crown had granted them control over Blue Lake.

As had been the case for Alianza, claims based on the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were not readily recognized by the twentieth-century U.S. legal system. Rather than turn to militancy, however, members of Taos Pueblo continued their patient appeals to the U.S. Congress as a means of regaining their sacred site. They also initiated a campaign to inspire public support for their claim, based on the notion of religious freedom—an idea that resonated with many Americans in the 1950s and 1960s.

As stated by Severino Martínez, Taos Pueblo Governor in the late 1950s:

Blue Lake is the most important of all our shrines because it is part of our life, it is our Indian church, we go there for good reason, like any other people would go to their denomination and like a shrine in Italy where the capital of the Roman Catholics worship is different: people go visit and give their humble words to God in any language that they speak. It is the same principle at the Blue Lake, we go over there and talk to our Great Spirit in our own language and talk to Nature and what is going to grow, and ask God Almighty, like anyone else would do.28

Between 1966 and 1971, a series of hearings transpired in both the House and Senate to decide the issue. Congress also conducted investigations into the economic and social situation faced by Native Americans across the nation generally. In early 1970, public opinion focused on the poor conditions endured on Indian Reservations, and, as stated by New Mexico Senator Clinton P. Anderson, “the Blue Lake Claim has become a symbol of American Indians’ plight.”29

Despite Anderson’s sympathy to the Taos claim, the bill he sponsored in the Senate was seen as a compromise measure. His proposal did not include the 48,000 acre watershed connected to the lake, a crucial part of the claim to Taos Pueblo people. Accordingly, the Taos Pueblo Council threw its support behind a bill proposed in the House that included their full claim. By the spring of 1970s, they secured the backing of six senators, including George McGovern of South Dakota, who served as chairman of the Senate Subcommittee of Indian Affairs.

Unwilling to leave the issue in the hands of the Congress, members of the pueblo initiated a mass media campaign to gain public support for their claims. They wrote hundreds of letters in a coordinated effort to pressure Congress to act. Archbishop of Santa Fe James Peter Davis, political cartoonist William “Bill” Mauldin, photographer Eliot Porter, and former director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs John Collier joined a national Blue Lake support committee to publicize the issue. Kim Agnew, the fourteen-year-old daughter of Vice President Spiro Agnew, rode horses with a group of Pueblo People in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to further publicize Taos Pueblo’s struggle for Blue Lake. Such efforts at promotion paid off; the story of their claim appeared on national television and in the New York Times and Washington Post.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

In December of 1970, Anderson’s compromise measure met defeat in the Senate, opening the way for the House bill to come to a vote. In early 1971, both houses of Congress voted overwhelmingly to support Taos Pueblo’s full claim to Blue Lake and the surrounding watershed. In the Senate, the bill passed by a measure of seventy to twelve, illustrating the impact of the pueblo’s publicity campaign in popularizing the conflict. Then, on August 14 and 15, 1971, the people of Taos Pueblo celebrated their victory by inviting outsiders to participate in festivities that included traditional dances and feasts, as well as commemorative speeches.

For Taos Pueblo and the AIPC, the return of Blue Lake marked a major civil rights victory, but Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache peoples continued to face conditions of poverty. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, several of New Mexico’s Native American groups began to investigate the prospect of gaming and tourism to boost their tribal economies and to promote self-determination. The Mescalero Apache people under the leadership of Wendell Chino were among the most successful.

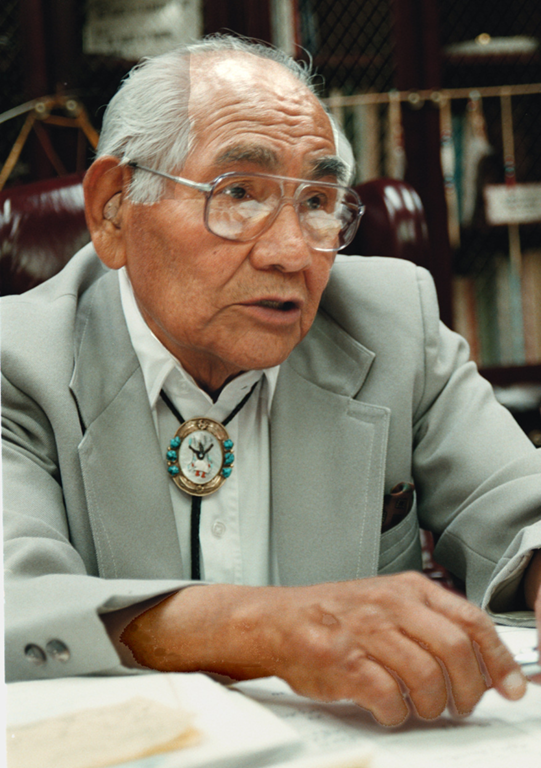

Courtesy of the Albuquerque Journal

Chino rose to a leadership position within the Mescalero tribe during the 1950s, a period of time during which federal policies toward Native Americans had turned toward the termination of the responsibility to protect Native trusts and self-determination that had been secured in the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act. A descendant of both Mescalero and Chiricahua ancestors, Chino was raised in a Christian household and became an ordained minister in his early twenties. Still, he possessed a clear understanding of and respect for Apache traditions.

His work as a minister prepared him to communicate his ideas clearly to people of different backgrounds. With the exception of a single four-year period, Chino served as the elected head of the Mescalero people continuously from 1953 until his death in 1998. His lengthy tenure was uncommon among Native American peoples, so much so that historians Joseph P. Sánchez, Robert L. Spude, and Art Gómez characterized Chino as “the autocratic chairman of the Mescalero Apache Tribal Council.”30 As Myla Vicenti Carpio and Peter Iverson have noted, he never shied from decisions that he felt would benefit the Mescalero people. As Chino himself remarked, “Too many tribal leaders want consensus because they’re afraid to exercise real leadership.”31

Central to all of Chino’s leadership decisions was the drive to maintain and expand Mescalero self-determination over their own political, social, and political affairs. Early in his political career, he resolved to support measures that would bring income to the Mescalero reservation, a place isolated from principal transportation corridors in south-central New Mexico. In the late 1950s, he worked with other members of the tribal council to create Apache Summit, a modest development geared to bring tourists to Mescalero lands during the ski season. When it opened, Apache Summit included a small motel, restaurant, and curio shop. The Mescalero tribe borrowed $200,000 dollars to construct the facility.

Early successes caused the Mescalero tribal council to take out further loans and construct new ski facilities and a large hotel. The Inn of the Mountain Gods opened in 1966, and it represented the connection between notions of self-determination and economic development. Along with the hotel, the resort included a golf course and two man-made lakes. Water to fill the lakes was pumped from one side of the reservation to the other, an action that drew criticism from the New Mexico State Engineer. Chino filed a lawsuit on behalf of the tribe, and argued “this is the aboriginal home of the Mescaleros. This is Apache Water.”32 A federal appeals court sided with the Mescaleros and the development went forward over the protests of the state engineer.

Courtesy of Jen Eastwood

As Chino initiated plans to diversify the Mescalero economy through the reintroduction of elk and fewer restrictions on hunting and fishing within reservation lands, the tribe once again came into direct conflict with state agencies. New Mexico’s Fish and Game Bureau continued to enforce state regulations on Mescalero lands until the tribe filed another suit against the state. In 1983, the Mescaleros once again emerged victorious.

Based on Chino’s continued reelection to tribal leadership, most Mescaleros seem to have supported his focus on self-determination. Yet by the early 1990s, many began to raise the question of the environmental and cultural costs of the measures that Chino so staunchly supported. The opposition gained traction when Chino supported an initiative to store nuclear waste on Mescalero lands.

Chino and supporters of the proposal on the tribal council referred to nuclear waste storage as an excellent opportunity to diversify the Mescalero economy. In their words, the initiative was “in the best interest of tribal people, utilizing the best technological knowledge and expertise in the nuclear waste field.”33

The Mescalero people did not share these sentiments. On January 31, 1995, a tribal vote defeated the measure by a 490 to 362 vote. Despite the defeat, Chino and his supporters circulated a petition that called for another vote on the issue. The second vote reversed the decision, passing the proposal by a measure of 593 to 372. Almost immediately after the election, opponents accused supporters of corruption. They alleged that tribal members had been promised a payment of $2,000 each if the measure passed. Additionally, members of the opposition, including some traditional female Mescalero leaders, reportedly received threats and harassment by the measure’s proponents. Rufina Marie Laws and Joseph Geronimo were among those who endured such treatment.

State officials, including New Mexico Attorney General Tom Udall, opposed the nuclear waste proposal and spoke out against the second vote. Udall believed that “tribal leadership [had] strong-armed members” to change the result.34 Within the Mescalero tribe, the episode fostered factionalism, conflict, and bitterness. Former council vice president Fred Peso emerged as a staunch opponent of Chino’s leadership, but much of the controversy abated when several national utilities revoked their support for the proposed nuclear waste relocation project. When the Power Company of Minnesota backed out of the deal, Congress discontinued funding for the proposal.

The debate over nuclear waste storage on Mescalero lands underscores the difficult balancing act between efforts to preserve sovereignty and self-determination on Native American lands. In 1984 Acoma Pueblo became the first in New Mexico to use bingo as a means of raising tribal funds; following the a Supreme Court decision in California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians in 1987, tribes across the country determined to build casinos as a means of economic revitalization.

Just five months before his death, Chino testified before a Senate subcommittee that “our sovereignty means the inalienable right to govern ourselves.”35 Although the means by which groups like the Mescaleros are able to promote their own economic well-being are often contested—even within the tribes themselves, proposals for new casinos or the storage of nuclear waste are often considered in terms of sovereignty and self-determination.

As the stories recounted in this chapter point out, civil rights efforts in New Mexico have taken various forms and achieved mixed results. Conflicts over access to land and resources are still part of daily life for nuevomexicanos, Pueblos, Apaches, and Navajos. The anti-discrimination measures of the 1950s and 1960s have contributed to increased opportunities for people of all racial backgrounds in the state, but poverty and the need for additional educational and economic opportunities continue. Self-determination remains an important goal for nuevomexicanos and indigenous peoples throughout the state.